The stab-in-the-back myth was an antisemitic conspiracy theory that was widely believed and promulgated in Germany after 1918. It maintained that the Imperial German Army did not lose World War I on the battlefield, but was instead betrayed by certain citizens on the home front – especially Jews, revolutionary socialists who fomented strikes and labour unrest, and republican politicians who had overthrown the House of Hohenzollern in the German Revolution of 1918–1919. Advocates of the myth denounced the German government leaders who had signed the Armistice of 11 November 1918 as the "November criminals".

The Spitting Image: Myth, Memory and the Legacy of Vietnam is a 1998 book by Vietnam veteran and sociology professor Jerry Lembcke. The book is an analysis of the widely believed narrative that American soldiers were spat upon and insulted by anti-war protesters upon returning home from the Vietnam War. The book examines the origin of the earliest stories; the popularization of the "spat-upon image" through Hollywood films and other media, and the role of print news media in perpetuating the now iconic image through which the history of the war and anti-war movement has come to be represented.

Vietnam syndrome is a term in U.S. politics that refers to public aversion to American overseas military involvements after the domestic controversy over the Vietnam War. In 1973, the U.S. ended combat operations in Vietnam. Since the early 1980s, some possible effects of Vietnam syndrome include public opinion against war, ending the active use of military conscription, a relative reluctance to deploy ground troops, and "Vietnam paralysis".

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, at sea, and in the air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices had been agreed with Bulgaria, the Ottoman Empire and Austria-Hungary. It was concluded after the German government sent a message to American president Woodrow Wilson to negotiate terms on the basis of a recent speech of his and the earlier declared "Fourteen Points", which later became the basis of the German surrender at the Paris Peace Conference, which took place the following year.

Opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War began with demonstrations in 1965 against the escalating role of the United States in the Vietnam War and grew into a broad social movement over the ensuing several years. This movement informed and helped shape the vigorous and polarizing debate, primarily in the United States, during the second half of the 1960s and early 1970s on how to end the Vietnam War.

National trauma is a concept in psychology and social psychology. A national trauma is one in which the effects of a trauma apply generally to the members of a collective group such as a country or other well-defined group of people. Trauma is an injury that has the potential to severely negatively affect an individual, whether physically or psychologically. Psychological trauma is a shattering of the fundamental assumptions that a person has about themselves and the world. An adverse experience that is unexpected, painful, extraordinary, and shocking results in interruptions in ongoing processes or relationships and may also create maladaptive responses. Such experiences can affect not only an individual but can also be collectively experienced by an entire group of people. Tragic experiences can collectively wound or threaten the national identity, that sense of belonging shared by a nation as a whole represented by tradition culture, language, and politics.

The Fort Hood Three were three United States Army soldiers – Private First Class James Johnson, Private David A. Samas, and Private Dennis Mora – who refused to be deployed to fight in the Vietnam War on June 30, 1966. This was the first public refusal of orders to Vietnam, and one of the earliest acts of resistance to the war from within the U.S. military. Their refusal was widely publicized and became a cause célèbre within the growing antiwar movement. They filed a federal suit against Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara and Secretary of the Army Stanley Resor to prevent their shipment to Southeast Asia and were court-martialed by the Army for insubordination.

Homecoming: When the Soldiers Returned From Vietnam is a book of selected correspondence published in 1989. Its genesis was a controversial newspaper column of 20 July 1987 in which Chicago Tribune syndicated columnist Bob Greene asked whether there was any truth to the folklore that Vietnam veterans had been spat upon when they returned from the war zone. Greene believed the tale was an urban legend. The overwhelming response to his original column led to four more columns, then to a book collection of the most notable responses.

GI coffeehouses were coffeehouses set up as part of the anti-war movement during the Vietnam War era as a method of fostering antiwar and anti-military sentiment within the U.S. military. They were mainly organized by civilian antiwar activists, though many GIs participated in establishing them as well. They were created in numerous cities and towns near U.S. military bases throughout the U.S as well as Germany and Japan. Due to the normal high turnover rate of GIs at military bases plus the military's response which often involved transfer, discharge and demotion, not to mention the hostility of the pro-military towns where many coffeehouses were located, most of them were short-lived, but a few survived for several years and "contributed to some of the GI movement's most significant actions". The first GI coffeehouse of the Vietnam era was set up in January 1968 and the last closed in 1974. There have been a few additional coffeehouses created during the U.S. led wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

A stab in the back may refer to:

The Stop Our Ship (SOS) movement, a component of the overall civilian and GI movements against the Vietnam War, was directed towards and developed on board U.S. Navy ships, particularly aircraft carriers heading to Southeast Asia. It was concentrated on and around major U.S. Naval stations and ships on the West Coast from mid-1970 to the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, and at its height involved tens of thousands of antiwar civilians, military personnel and veterans. It was sparked by the tactical shift of U.S. combat operations in Southeast Asia from the ground to the air. As the ground war stalemated and Army grunts increasingly refused to fight or resisted the war in various other ways, the U.S. “turned increasingly to air bombardment”. By 1972 there were twice as many Seventh Fleet aircraft carriers in the Gulf of Tonkin as previously and the antiwar movement, which was at its height in the U.S. and worldwide, became a significant factor in the Navy. While no ships were actually prevented from returning to war, the campaigns, combined with the broad antiwar and rebellious sentiment of the times, stirred up substantial difficulties for the Navy, including active duty sailors refusing to sail with their ships, circulating petitions and antiwar propaganda on board, disobeying orders, and committing sabotage, as well as persistent civilian antiwar activity in support of dissident sailors. Several ship combat missions were postponed or altered and one ship was delayed by a combination of a civilian blockade and crewmen jumping overboard.

The Intrepid Four were a group of United States Navy sailors who grew to oppose what they called "the American aggression in Vietnam" and publicly deserted from the USS Intrepid in October 1967 as it docked in Japan during the Vietnam War. They were among the first American troops whose desertion was publicly announced during the war and the first within the U.S. Navy. The fact that it was a group, and not just an individual, made it more newsworthy.

The claim that there was a Jewish war against Nazi Germany is an antisemitic conspiracy theory promoted in Nazi propaganda which asserts that the Jews, framed within the theory as a single historical actor, started World War II and sought the destruction of Germany. Alleging that war was declared in 1939 by Chaim Weizmann, president of the World Zionist Organization, Nazis used this false notion to justify the persecution of Jews under German control on the grounds that the Holocaust was justified self-defense. Since the end of World War II, the conspiracy theory has been popular among neo-Nazis and Holocaust deniers.

Jeffrey P. Kimball is an American historian and emeritus professor at Miami University. Among the ideas that Kimball developed was the idea of a Vietnam stab-in-the-back myth. He also argued that threats to use nuclear weapons had not been effective at advancing the United States' foreign policy goals either in the Korean War, Vietnam War, or the First Taiwan Strait Crisis. Historian Luke Nichter wrote that Kimball's books "shaped future works, and these volumes on my shelves stand as a reminder that my own work on the Nixon tapes would not have happened without them". According to historian Ken Hughes, Kimball is "the leading scholar of the 'decent interval'": the idea that Nixon eventually settled for securing a "decent interval" before South Vietnamese defeat. Hughes regrets that Kimball's work is "virtually unknown" outside academia.

Decent interval is a theory regarding the end of the Vietnam War which argues that from 1971 or 1972, the Nixon Administration abandoned the goal of preserving South Vietnam and instead aimed to save face by preserving a "decent interval" between withdrawal and South Vietnamese collapse. Therefore, Nixon could avoid becoming the first United States president to lose a war.

According to the American sniper Carlos Hathcock, Apache was a female sniper and interrogator for the Viet Cong during the War in Vietnam. While no real name is given by Hathcock, he states she was known by the US military as "Apache", because of her methods of torturing US Marines and ARVN troops for information and then letting them bleed to death.

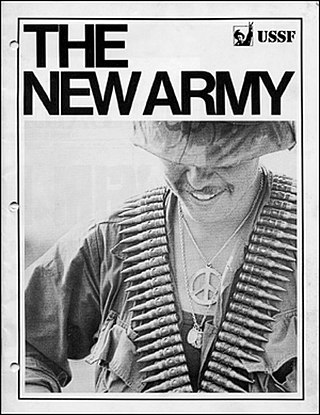

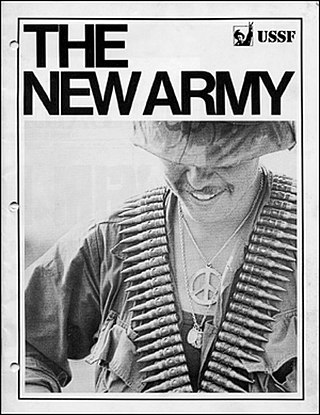

The United States Servicemen's Fund (USSF) was a support organization for soldier and sailor resistance to the Vietnam War and the U.S. military that was founded in late 1968 and continued through 1973. It was an "umbrella agency" that funded GI underground newspapers and GI Coffeehouses, as well as providing logistical support for the GI antiwar movement ranging from antiwar films and speakers to legal assistance and staff. USSF described itself as supporting a GI defined movement "to work for an end to the Viet Nam war" and "to eradicate the indoctrination and oppression that they see so clearly every day."

Soldiers in Revolt: GI Resistance During the Vietnam War was the first comprehensive exploration of the disaffection, resistance, rebellion and organized opposition to the Vietnam War within the ranks of the U.S. Armed Forces. It was the first book written by David Cortright, a Vietnam veteran who is currently Professor Emeritus and special adviser for policy studies at the Keough School of Global Affairs and Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame, and the author, co-author, editor or co-editor of 22 books. Originally published as the war was ending in 1975, it was republished in 2005 with an introduction by the well known progressive historian Howard Zinn. Despite being first published 49 years ago, it remains the definitive history of this often ignored subject. The book argues persuasively, with encyclopedic rigor, the still under appreciated fact that by the early 1970s the U.S. armed forces, particularly its ground forces, were essentially breaking down; experiencing a deep crises of moral, discipline and combat effectiveness. Cortright reveals, for example, that in fiscal year 1972, there were more conscientious objectors than draftees, and precipitous declines in both officer enrollments and non-officer enlistments. He also documents "staggering level[s]" of desertions, increasing nearly 400% in the Army from 1966 to 1971. Perhaps more importantly, Cortright makes a convincing case for this unraveling being both a product and an integral part of the anti-Vietnam War sentiment and movement widespread within U.S. society and worldwide at the time. He documents hundreds of GI antiwar and antimilitary organizations, thousands of individual and group acts of resistance, hundreds of GI underground newspapers, and highlights the role of Black GIs militantly fighting racism and the war. This is where the book stands alone as the first and most systematic study of the antiwar and dissident movements impact and growth within the U.S. armed forces during the Vietnam War. While other books, articles and studies have examined this subject, none have done it as thoroughly and systematically.

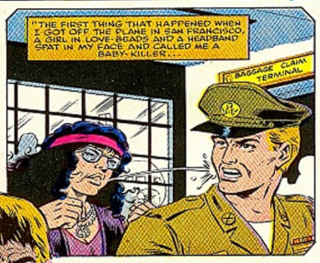

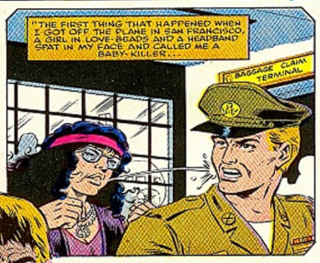

There is a persistent myth or misconception that many Vietnam veterans were spat on and vilified by antiwar protesters during the late 1960s and early 1970s. These stories, which overwhelmingly surfaced many years after the war, usually involve an antiwar female spitting on a veteran, often yelling "baby killer". Most occur in U.S. civilian airports, usually San Francisco International, as GIs returned from the war zone in their uniforms.