In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleotide sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mitosis, or meiosis or other types of damage to DNA, which then may undergo error-prone repair, cause an error during other forms of repair, or cause an error during replication. Mutations may also result from insertion or deletion of segments of DNA due to mobile genetic elements.

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charles Darwin popularised the term "natural selection", contrasting it with artificial selection, which in his view is intentional, whereas natural selection is not.

In genetics, dominance is the phenomenon of one variant (allele) of a gene on a chromosome masking or overriding the effect of a different variant of the same gene on the other copy of the chromosome. The first variant is termed dominant and the second recessive. This state of having two different variants of the same gene on each chromosome is originally caused by a mutation in one of the genes, either new or inherited. The terms autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive are used to describe gene variants on non-sex chromosomes (autosomes) and their associated traits, while those on sex chromosomes (allosomes) are termed X-linked dominant, X-linked recessive or Y-linked; these have an inheritance and presentation pattern that depends on the sex of both the parent and the child. Since there is only one copy of the Y chromosome, Y-linked traits cannot be dominant nor recessive. Additionally, there are other forms of dominance such as incomplete dominance, in which a gene variant has a partial effect compared to when it is present on both chromosomes, and co-dominance, in which different variants on each chromosome both show their associated traits.

Molecular evolution is the process of change in the sequence composition of cellular molecules such as DNA, RNA, and proteins across generations. The field of molecular evolution uses principles of evolutionary biology and population genetics to explain patterns in these changes. Major topics in molecular evolution concern the rates and impacts of single nucleotide changes, neutral evolution vs. natural selection, origins of new genes, the genetic nature of complex traits, the genetic basis of speciation, evolution of development, and ways that evolutionary forces influence genomic and phenotypic changes.

The neutral theory of molecular evolution holds that most evolutionary changes occur at the molecular level, and most of the variation within and between species, are due to random genetic drift of mutant alleles that are selectively neutral. The theory applies only for evolution at the molecular level, and is compatible with phenotypic evolution being shaped by natural selection as postulated by Charles Darwin. The neutral theory allows for the possibility that most mutations are deleterious, but holds that because these are rapidly removed by natural selection, they do not make significant contributions to variation within and between species at the molecular level. A neutral mutation is one that does not affect an organism's ability to survive and reproduce. The neutral theory assumes that most mutations that are not deleterious are neutral rather than beneficial. Because only a fraction of gametes are sampled in each generation of a species, the neutral theory suggests that a mutant allele can arise within a population and reach fixation by chance, rather than by selective advantage.

Population genetics is a subfield of genetics that deals with genetic differences within and between populations, and is a part of evolutionary biology. Studies in this branch of biology examine such phenomena as adaptation, speciation, and population structure.

In biology, polymorphism is the occurrence of two or more clearly different morphs or forms, also referred to as alternative phenotypes, in the population of a species. To be classified as such, morphs must occupy the same habitat at the same time and belong to a panmictic population.

Balancing selection refers to a number of selective processes by which multiple alleles are actively maintained in the gene pool of a population at frequencies larger than expected from genetic drift alone. This can happen by various mechanisms, in particular, when the heterozygotes for the alleles under consideration have a higher fitness than the homozygote. In this way genetic polymorphism is conserved.

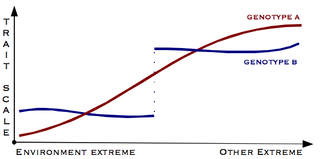

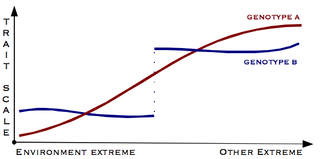

Canalisation is a measure of the ability of a population to produce the same phenotype regardless of variability of its environment or genotype. It is a form of evolutionary robustness. The term was coined in 1942 by C. H. Waddington to capture the fact that "developmental reactions, as they occur in organisms submitted to natural selection...are adjusted so as to bring about one definite end-result regardless of minor variations in conditions during the course of the reaction". He used this word rather than robustness to take into account that biological systems are not robust in quite the same way as, for example, engineered systems.

The Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution is an influential monograph written in 1983 by Japanese evolutionary biologist Motoo Kimura. While the neutral theory of molecular evolution existed since his article in 1968, Kimura felt the need to write a monograph with up-to-date information and evidences showing the importance of his theory in evolution.

Neutral mutations are changes in DNA sequence that are neither beneficial nor detrimental to the ability of an organism to survive and reproduce. In population genetics, mutations in which natural selection does not affect the spread of the mutation in a species are termed neutral mutations. Neutral mutations that are inheritable and not linked to any genes under selection will either be lost or will replace all other alleles of the gene. This loss or fixation of the gene proceeds based on random sampling known as genetic drift. A neutral mutation that is in linkage disequilibrium with other alleles that are under selection may proceed to loss or fixation via genetic hitchhiking and/or background selection.

An evolutionary landscape is a metaphor or a construct used to think about and visualize the processes of evolution acting on a biological entity. This entity can be viewed as searching or moving through a search space. For example, the search space of a gene would be all possible nucleotide sequences. The search space is only part of an evolutionary landscape. The final component is the "y-axis", which is usually fitness. Each value along the search space can result in a high or low fitness for the entity. If small movements through search space cause changes in fitness that are relatively small, then the landscape is considered smooth. Smooth landscapes happen when most fixed mutations have little to no effect on fitness, which is what one would expect with the neutral theory of molecular evolution. In contrast, if small movements result in large changes in fitness, then the landscape is said to be rugged. In either case, movement tends to be toward areas of higher fitness, though usually not the global optima.

Genetic assimilation is a process described by Conrad H. Waddington by which a phenotype originally produced in response to an environmental condition, such as exposure to a teratogen, later becomes genetically encoded via artificial selection or natural selection. Despite superficial appearances, this does not require the (Lamarckian) inheritance of acquired characters, although epigenetic inheritance could potentially influence the result. Waddington stated that genetic assimilation overcomes the barrier to selection imposed by what he called canalization of developmental pathways; he supposed that the organism's genetics evolved to ensure that development proceeded in a certain way regardless of normal environmental variations.

A suppressor mutation is a second mutation that alleviates or reverts the phenotypic effects of an already existing mutation in a process defined synthetic rescue. Genetic suppression therefore restores the phenotype seen prior to the original background mutation. Suppressor mutations are useful for identifying new genetic sites which affect a biological process of interest. They also provide evidence between functionally interacting molecules and intersecting biological pathways.

In population genetics, fixation is the change in a gene pool from a situation where there exists at least two variants of a particular gene (allele) in a given population to a situation where only one of the alleles remains. In the absence of mutation or heterozygote advantage, any allele must eventually be lost completely from the population or fixed. Whether a gene will ultimately be lost or fixed is dependent on selection coefficients and chance fluctuations in allelic proportions. Fixation can refer to a gene in general or particular nucleotide position in the DNA chain (locus).

The history of molecular evolution starts in the early 20th century with "comparative biochemistry", but the field of molecular evolution came into its own in the 1960s and 1970s, following the rise of molecular biology. The advent of protein sequencing allowed molecular biologists to create phylogenies based on sequence comparison, and to use the differences between homologous sequences as a molecular clock to estimate the time since the last common ancestor. In the late 1960s, the neutral theory of molecular evolution provided a theoretical basis for the molecular clock, though both the clock and the neutral theory were controversial, since most evolutionary biologists held strongly to panselectionism, with natural selection as the only important cause of evolutionary change. After the 1970s, nucleic acid sequencing allowed molecular evolution to reach beyond proteins to highly conserved ribosomal RNA sequences, the foundation of a reconceptualization of the early history of life.

A fixed allele is an allele that is the only variant that exists for that gene in all the population. A fixed allele is homozygous for all members of the population. The term allele normally refers to one variant gene out of several possible for a particular locus in the DNA. When all but one allele go extinct and only one remains, that allele is said to be fixed.

Robustness of a biological system is the persistence of a certain characteristic or trait in a system under perturbations or conditions of uncertainty. Robustness in development is known as canalization. According to the kind of perturbation involved, robustness can be classified as mutational, environmental, recombinational, or behavioral robustness etc. Robustness is achieved through the combination of many genetic and molecular mechanisms and can evolve by either direct or indirect selection. Several model systems have been developed to experimentally study robustness and its evolutionary consequences.

Epistasis is a phenomenon in genetics in which the effect of a gene mutation is dependent on the presence or absence of mutations in one or more other genes, respectively termed modifier genes. In other words, the effect of the mutation is dependent on the genetic background in which it appears. Epistatic mutations therefore have different effects on their own than when they occur together. Originally, the term epistasis specifically meant that the effect of a gene variant is masked by that of a different gene.

This glossary of evolutionary biology is a list of definitions of terms and concepts used in the study of evolutionary biology, population biology, speciation, and phylogenetics, as well as sub-disciplines and related fields. For additional terms from related glossaries, see Glossary of genetics, Glossary of ecology, and Glossary of biology.