Related Research Articles

Dementia is a syndrome associated with many neurodegenerative diseases, characterized by a general decline in cognitive abilities that impacts a person's ability to perform everyday activities. This typically involves problems with memory, thinking, behavior, and motor control. Aside from memory impairment and a disruption in thought patterns, the most common symptoms of dementia include emotional problems, difficulties with language, and decreased motivation. The symptoms may be described as occurring in a continuum over several stages. Dementia ultimately has a significant effect on the individual, their caregivers, and their social relationships in general. A diagnosis of dementia requires the observation of a change from a person's usual mental functioning and a greater cognitive decline than might be caused by the normal aging process.

Delirium is a specific state of acute confusion attributable to the direct physiological consequence of a medical condition, effects of a psychoactive substance, or multiple causes, which usually develops over the course of hours to days. As a syndrome, delirium presents with disturbances in attention, awareness, and higher-order cognition. People with delirium may experience other neuropsychiatric disturbances, including changes in psychomotor activity, disrupted sleep-wake cycle, emotional disturbances, disturbances of consciousness, or, altered state of consciousness, as well as perceptual disturbances, although these features are not required for diagnosis.

Cognitive disorders (CDs), also known as neurocognitive disorders (NCDs), are a category of mental health disorders that primarily affect cognitive abilities including learning, memory, perception, and problem-solving. Neurocognitive disorders include delirium, mild neurocognitive disorders, and major neurocognitive disorder. They are defined by deficits in cognitive ability that are acquired, typically represent decline, and may have an underlying brain pathology. The DSM-5 defines six key domains of cognitive function: executive function, learning and memory, perceptual-motor function, language, complex attention, and social cognition.

The mini–mental state examination (MMSE) or Folstein test is a 30-point questionnaire that is used extensively in clinical and research settings to measure cognitive impairment. It is commonly used in medicine and allied health to screen for dementia. It is also used to estimate the severity and progression of cognitive impairment and to follow the course of cognitive changes in an individual over time; thus making it an effective way to document an individual's response to treatment. The MMSE's purpose has been not, on its own, to provide a diagnosis for any particular nosological entity.

The Abbreviated Mental Test score (AMTS) is a 10-point test for rapidly assessing elderly patients for the possibility of dementia. It was first used in 1972, and is now sometimes also used to assess for mental confusion and other cognitive impairments.

Prostate cancer screening is the screening process used to detect undiagnosed prostate cancer in men without signs or symptoms. When abnormal prostate tissue or cancer is found early, it may be easier to treat and cure, but it is unclear if early detection reduces mortality rates.

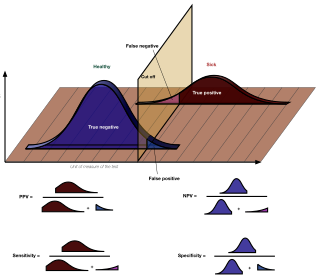

In medicine and statistics, sensitivity and specificity mathematically describe the accuracy of a test that reports the presence or absence of a medical condition. If individuals who have the condition are considered "positive" and those who do not are considered "negative", then sensitivity is a measure of how well a test can identify true positives and specificity is a measure of how well a test can identify true negatives:

Clouding of consciousness, also called brain fog or mental fog, occurs when a person is slightly less wakeful or aware than normal. They are less aware of time and their surroundings, and find it difficult to pay attention. People describe this subjective sensation as their mind being "foggy".

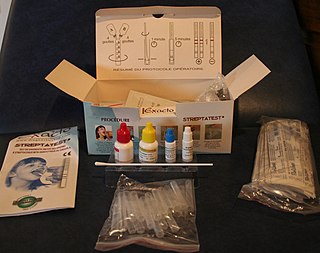

Point-of-care testing (POCT), also called near-patient testing or bedside testing, is defined as medical diagnostic testing at or near the point of care—that is, at the time and place of patient care. This contrasts with the historical pattern in which testing was wholly or mostly confined to the medical laboratory, which entailed sending off specimens away from the point of care and then waiting hours or days to learn the results, during which time care must continue without the desired information.

The Alvarado score is a clinical scoring system used in the diagnosis of appendicitis. Alvarado scoring has largely been superseded as a clinical prediction tool by the Appendicitis Inflammatory Response score.

The Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) is a questionnaire that can be filled out by a relative or other supporter of an older person to determine whether that person has declined in cognitive functioning. The IQCODE is used as a screening test for dementia. If the person is found to have significant cognitive decline, then this needs to be followed up with a medical examination to determine whether dementia is present.

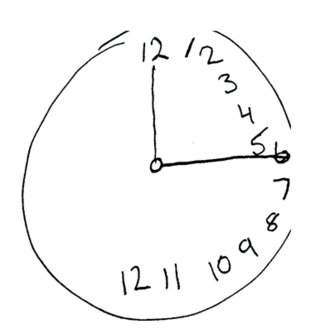

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a widely used screening assessment for detecting cognitive impairment. It was created in 1996 by Ziad Nasreddine in Montreal, Quebec. It was validated in the setting of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and has subsequently been adopted in numerous other clinical settings. This test consists of 30 points and takes 10 minutes for the individual to complete. The original English version is performed in seven steps, which may change in some countries dependent on education and culture. The basics of this test include short-term memory, executive function, attention, focus, and more.

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) is a multiple-choice self-report inventory that is used as a screening and diagnostic tool for mental health disorders of depression, anxiety, alcohol, eating, and somatoform disorders. It is the self-report version of the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD), a diagnostic tool developed in the mid-1990s by Pfizer Inc. The length of the original assessment limited its feasibility; consequently, a shorter version, consisting of 11 multi-part questions - the Patient Health Questionnaire was developed and validated.

The triple test score is a diagnostic tool for examining potentially cancerous breasts. Diagnostic accuracy of the triple test score is nearly 100%. Scoring includes using the procedures of physical examination, mammography and needle biopsy. If the results of a triple test score are greater than five, an excisional biopsy is indicated.

The Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination (ACE) and its subsequent versions are neuropsychological tests used to identify cognitive impairment in conditions such as dementia.

The Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) is a self-report questionnaire designed to help detect bipolar disorder. It focuses on symptoms of hypomania and mania, which are the mood states that separate bipolar disorders from other types of depression and mood disorder. It has 5 main questions, and the first question has 13 parts, for a total of 17 questions. The MDQ was originally tested with adults, but it also has been studied in adolescents ages 11 years and above. It takes approximately 5–10 minutes to complete. In 2006, a parent-report version was created to allow for assessment of bipolar symptoms in children or adolescents from a caregiver perspective, with the research looking at youths as young as 5 years old. The MDQ has become one of the most widely studied and used questionnaires for bipolar disorder, and it has been translated into more than a dozen languages.

The nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a depressive symptom scale and diagnostic tool introduced in 2001 to screen adult patients in primary care settings. The instrument assesses for the presence and severity of depressive symptoms and a possible depressive disorder. The PHQ-9 is a component of the larger self-administered Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), but can be used as a stand-alone instrument. The PHQ is part of Pfizer's larger suite of trademarked products, called the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD). The PHQ-9 takes less than three minutes to complete. It is scored by simply adding up the individual items' scores. Each of the nine items reflects a DSM-5 symptom of depression. Primary care providers can use the PHQ-9 to screen for possible depression in patients.

The Ritvo Autism & Asperger Diagnostic Scale (RAADS) is a psychological self-rating scale developed by Dr. Riva Ariella Ritvo. An abridged and translated 14 question version was then developed at the Department of Clinical Neuroscience at the Karolinska Institute, to aid in the identification of patients who may have undiagnosed ASD.

The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) is a diagnostic tool developed to allow physicians and nurses to identify delirium in the healthcare setting. It was designed to be brief and based on criteria from the third edition-revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III-R). The CAM rates four diagnostic features, including acute onset and fluctuating course, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness. The CAM requires that a brief cognitive test is performed before it is completed. It has been translated into more than 20 languages and adapted for use across multiple settings.

The Cogstate Brief Battery (CBB) is a computer-based cognitive assessment used in clinical trials, healthcare, and academic research to measure neurological cognition. It was developed by Cogstate Ltd.

References

- ↑ Delirium Archived 2019-05-13 at the Wayback Machine , Symptom Finder online.

- 1 2 Wilson, Jo Ellen; Mart, Matthew F.; Cunningham, Colm; Shehabi, Yahya; Girard, Timothy D.; MacLullich, Alasdair M. J.; Slooter, Arjen J. C.; Ely, E. Wesley (2020-11-12). "Delirium". Nature Reviews. Disease Primers. 6 (1): 90. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00223-4 . ISSN 2056-676X. PMC 9012267 . PMID 33184265.

- ↑ Calf, Agneta H.; Pouw, Maaike A.; van Munster, Barbara C.; Burgerhof, Johannes G. M.; de Rooij, Sophia E.; Smidt, Nynke (2021-01-08). "Screening instruments for cognitive impairment in older patients in the Emergency Department: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Age and Ageing. 50 (1): 105–112. doi:10.1093/ageing/afaa183. ISSN 1468-2834. PMC 7793600 . PMID 33009909.

- 1 2 "4AT – RAPID CLINICAL TEST FOR DELIRIUM" . Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ↑ "References". 4AT - RAPID CLINICAL TEST FOR DELIRIUM. Retrieved 2022-02-26.

- 1 2 Tieges, Zoë; Maclullich, Alasdair M. J.; Anand, Atul; Brookes, Claire; Cassarino, Marica; O'connor, Margaret; Ryan, Damien; Saller, Thomas; Arora, Rakesh C.; Chang, Yue; Agarwal, Kathryn (2020-11-11). "Diagnostic accuracy of the 4AT for delirium detection in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis". Age and Ageing. 50 (3): 733–743. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa224 . ISSN 1468-2834. PMC 8099016 . PMID 33196813.

- ↑ Shenkin, Susan D.; Fox, Christopher; Godfrey, Mary; Siddiqi, Najma; Goodacre, Steve; Young, John; Anand, Atul; Gray, Alasdair; Hanley, Janet; MacRaild, Allan; Steven, Jill (2019-07-24). "Delirium detection in older acute medical inpatients: a multicentre prospective comparative diagnostic test accuracy study of the 4AT and the confusion assessment method". BMC Medicine. 17 (1): 138. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1367-9 . ISSN 1741-7015. PMC 6651960 . PMID 31337404.

- ↑ Arnold, Elizabeth; Finucane, Anne M; Taylor, Stacey; Spiller, Juliet A; O’Rourke, Siobhan; Spenceley, Julie; Carduff, Emma; Tieges, Zoë; MacLullich, Alasdair MJ (May 2024). "The 4AT, a rapid delirium detection tool for use in hospice inpatient units: Findings from a validation study". Palliative Medicine. 38 (5): 535–545. doi:10.1177/02692163241242648. ISSN 0269-2163.

- ↑ "National Audit of Dementia Reports and Resources". RC PSYCH ROYAL COLLEGE OF PSYCHIATRISTS. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ↑ "National Hip Fracture Database: Annual Report 2019" (PDF). National Hip Fracture Database. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ↑ MacLullich, AM; Shenkin, SD; Goodacre, S; Godfrey, M; Hanley, J; Stíobhairt, A; Lavender, E; Boyd, J; Stephen, J; Weir, C; MacRaild, A; Steven, J; Black, P; Diernberger, K; Hall, P; Tieges, Z; Fox, C; Anand, A; Young, J; Siddiqi, N; Gray, A (August 2019). "The 4 'A's test for detecting delirium in acute medical patients: a diagnostic accuracy study". Health Technology Assessment. 23 (40): 1–194. doi:10.3310/hta23400. PMC 6709509 . PMID 31397263.

- ↑ Dormandy, L; Mufti, S; Higgins, E; Bailey, C; Dixon, M (October 2019). "Shifting the focus: A QI project to improve the management of delirium in patients with hip fracture". Future Healthcare Journal. 6 (3): 215–219. doi:10.7861/fhj.2019-0006. PMC 6798014 . PMID 31660529.

- ↑ Bearn, A; Lea, W; Kusznir, J (29 November 2018). "Improving the identification of patients with delirium using the 4AT assessment". Nursing Older People. 30 (7): 18–27. doi:10.7748/nop.2018.e1060. PMID 30426731. S2CID 53303149.

- ↑ E, Vardy; N, Collins; U, Grover; R, Thompson; A, Bagnall; G, Clarke; S, Heywood; B, Thompson; L, Wintle (2020-05-16). "Use of a Digital Delirium Pathway and Quality Improvement to Improve Delirium Detection in the Emergency Department and Outcomes in an Acute Hospital". Age and Ageing. 49 (4): 672–678. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa069 . PMID 32417926.

- ↑ Casey, P; Cross, W; Mart, MW; Baldwin, C; Riddell, K; Dārziņš, P (March 2019). "Hospital discharge data under-reports delirium occurrence: results from a point prevalence survey of delirium in a major Australian health service". Internal Medicine Journal. 49 (3): 338–344. doi:10.1111/imj.14066. PMID 30091294. S2CID 205209486.

- ↑ Bellelli, PG; Biotto, M; Morandi, A; Meagher, D; Cesari, M; Mazzola, P; Annoni, G; Zambon, A (December 2019). "The relationship among frailty, delirium and attentional tests to detect delirium: a cohort study". European Journal of Internal Medicine. 70: 33–38. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2019.09.008. PMID 31761505. S2CID 208277203.

- ↑ Bellelli, G; Morandi, A; Di Santo, SG; Mazzone, A; Cherubini, A; Mossello, E; Bo, M; Bianchetti, A; Rozzini, R; Zanetti, E; Musicco, M; Ferrari, A; Ferrara, N; Trabucchi, M; Italian Study Group on Delirium, (ISGoD). (18 July 2016). ""Delirium Day": a nationwide point prevalence study of delirium in older hospitalized patients using an easy standardized diagnostic tool". BMC Medicine. 14: 106. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0649-8 . PMC 4950237 . PMID 27430902.

- ↑ Davis, D; Richardson, S; Hornby, J; Bowden, H; Hoffmann, K; Weston-Clarke, M; Green, F; Chaturvedi, N; Hughes, A; Kuh, D; Sampson, E; Mizoguchi, R; Cheah, KL; Romain, M; Sinha, A; Jenkin, R; Brayne, C; MacLullich, A (9 February 2018). "The delirium and population health informatics cohort study protocol: ascertaining the determinants and outcomes from delirium in a whole population". BMC Geriatrics. 18 (1): 45. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0742-2 . PMC 5807842 . PMID 29426299.

- ↑ "SIGN 157 Delirium: Risk reduction and management of delirium". www.sign.ac.uk. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ↑ "Delirium Clinical Care Standard" (PDF). Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ↑ "National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2. Standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. Additional Implemenation Guidance March 2020" . Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ↑ "Delirium Quality Standard: Tools for Implementation". Quorum. Retrieved 2021-05-13.

- ↑ "Integrated Care Pathways and Delirium Algorithms". dementiapathways.ie. Retrieved 2021-05-13.

- ↑ "4AT calculator". www.signdecisionsupport.uk. Retrieved 2021-05-13.

- ↑ Penfold, Rose S.; Squires, Charlotte; Angus, Alisa; Shenkin, Susan D.; Ibitoye, Temi; Tieges, Zoë; Neufeld, Karin J.; Avelino‐Silva, Thiago J.; Davis, Daniel; Anand, Atul; Duckworth, Andrew D.; Guthrie, Bruce; MacLullich, Alasdair M. J. (2024-01-19). "Delirium detection tools show varying completion rates and positive score rates when used at scale in routine practice in general hospital settings: A systematic review". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. doi: 10.1111/jgs.18751 . ISSN 0002-8614.

- 1 2 Anand, Atul; Cheng, Michael; Ibitoye, Temi; Maclullich, Alasdair M J; Vardy, Emma R L C (2022-03-01). "Positive scores on the 4AT delirium assessment tool at hospital admission are linked to mortality, length of stay and home time: two-centre study of 82,770 emergency admissions". Age and Ageing. 51 (3): afac051. doi:10.1093/ageing/afac051. ISSN 0002-0729. PMC 8923813 . PMID 35292792.

- ↑ Inouye, S. K.; van Dyck, C. H.; Alessi, C. A.; Balkin, S.; Siegal, A. P.; Horwitz, R. I. (1990-12-15). "Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium". Annals of Internal Medicine. 113 (12): 941–948. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 2240918.

- ↑ Tieges, Zoë; McGrath, Aisling; Hall, Roanna J.; Maclullich, Alasdair M. J. (December 2013). "Abnormal level of arousal as a predictor of delirium and inattention: an exploratory study". The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 21 (12): 1244–1253. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2013.05.003. ISSN 1545-7214. PMID 24080383.

- ↑ Chester, Jennifer G.; Beth Harrington, Mary; Rudolph, James L.; VA Delirium Working Group (May 2012). "Serial administration of a modified Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale for delirium screening". Journal of Hospital Medicine. 7 (5): 450–453. doi:10.1002/jhm.1003. ISSN 1553-5606. PMC 4880479 . PMID 22173963.

- 1 2 European Delirium Association; American Delirium Society (2014-10-08). "The DSM-5 criteria, level of arousal and delirium diagnosis: inclusiveness is safer". BMC Medicine. 12: 141. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0141-2 . ISSN 1741-7015. PMC 4177077 . PMID 25300023.

- ↑ Yates, Catherine; Stanley, Neil; Cerejeira, Joaquim M.; Jay, Roger; Mukaetova-Ladinska, Elizabeta B. (March 2009). "Screening instruments for delirium in older people with an acute medical illness". Age and Ageing. 38 (2): 235–237. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn285 . hdl: 10400.4/1170 . ISSN 1468-2834. PMID 19110484.

- ↑ Hasegawa, Tadashi; Seo, Tomomi; Kubota, Yoko; Sudo, Tomoko; Yokota, Kumi; Miyazaki, Nao; Muranaka, Akira; Hirano, Shigeki; Yamauchi, Atsushi; Nagashima, Kengo; Iyo, Masaomi (January 2022). "Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the 4A's Test for delirium screening in the elderly patient". Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 67: 102918. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102918. ISSN 1876-2026. PMID 34798384. S2CID 243841870.

- ↑ Johansson, Yvonne A.; Tsevis, Theofanis; Nasic, Salmir; Gillsjö, Catharina; Johansson, Linda; Bogdanovic, Nenad; Kenne Sarenmalm, Elisabeth (2021-10-18). "Diagnostic accuracy and clinical applicability of the Swedish version of the 4AT assessment test for delirium detection, in a mixed patient population and setting". BMC Geriatrics. 21 (1): 568. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02493-3 . ISSN 1471-2318. PMC 8522056 . PMID 34663229.

- 1 2 Chang, Yue; Ragheb, Sandra M.; Oravec, Nebojsa; Kent, David; Nugent, Kristina; Cornick, Alexandra; Hiebert, Brett; Rudolph, James L.; MacLullich, Alasdair M. J.; Arora, Rakesh C. (2021-06-01). "Diagnostic accuracy of the "4 A's Test" delirium screening tool for the postoperative cardiac surgery ward". The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 165 (3): S0022–5223(21)00876–X. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.05.031. hdl: 20.500.11820/a4b90ba6-dd24-428b-b038-df1670781523 . ISSN 1097-685X. PMID 34243932. S2CID 235786438.

- ↑ Delgado-Parada, E.; Morillo-Cuadrado, D.; Saiz-Ruiz, J; Cebollada-Gracia, A.; Ayuso-Mateos, J. L.; Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. (2022-02-10). "Diagnostic accuracy of the Spanish version of the 4AT scale (4AT-ES) for delirium screening in older inpatients". The European Journal of Psychiatry. 36 (3): 182–190. doi:10.1016/j.ejpsy.2022.01.003. ISSN 0213-6163. S2CID 246767623.

- ↑ Evensen, Sigurd; Hylen Ranhoff, Anette; Lydersen, Stian; Saltvedt, Ingvild (August 2021). "The delirium screening tool 4AT in routine clinical practice: prediction of mortality, sensitivity and specificity". European Geriatric Medicine. 12 (4): 793–800. doi:10.1007/s41999-021-00489-1. ISSN 1878-7649. PMC 8321971 . PMID 33813725.

- ↑ Sepúlveda, Esteban; Bermúdez, Ester; González, Dulce; Cotino, Paula; Viñuelas, Eva; Palma, José; Ciutat, Marta; Grau, Imma; Vilella, Elisabet; Trzepacz, Paula T.; Franco, José G. (May 2021). "Validation of the Delirium Diagnostic Tool-Provisional (DDT-Pro) in a skilled nursing facility and comparison to the 4 'A's test (4AT)". General Hospital Psychiatry. 70: 116–123. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.03.010. ISSN 1873-7714. PMID 33813146. S2CID 233029095.

- ↑ Shenkin, Susan D.; Fox, Christopher; Godfrey, Mary; Siddiqi, Najma; Goodacre, Steve; Young, John; Anand, Atul; Gray, Alasdair; Hanley, Janet; MacRaild, Allan; Steven, Jill (2019-07-24). "Delirium detection in older acute medical inpatients: a multicentre prospective comparative diagnostic test accuracy study of the 4AT and the confusion assessment method". BMC Medicine. 17 (1): 138. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1367-9 . ISSN 1741-7015. PMC 6651960 . PMID 31337404.

- 1 2 "4AT – RAPID CLINICAL TEST FOR DELIRIUM" . Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- ↑ "Delirium detection in routine clinical care: two basic processes". DeliriumWords.com. 15 June 2020. Retrieved 2021-05-13.

- ↑ Zastrow, Inke; Tohsche, Peter; Loewen, Theresa; Vogt, Birgit; Feige, Melanie; Behnke, Martina; Wolff, Antje; Kiefmann, Rainer; Olotu, Cynthia (2021-09-01). "Comparison of the '4-item assessment test' and 'nursing delirium screening scale' delirium screening tools on non-intensive care unit wards: A prospective mixed-method approach". European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 38 (9): 957–965. doi:10.1097/EJA.0000000000001470. ISSN 1365-2346. PMID 33606422. S2CID 231964159.

- ↑ "NEWS2: Additional implementation guidance". RCP London. 2020-04-06. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- ↑ Voyer, Philippe; Champoux, Nathalie; Desrosiers, Johanne; Landreville, Philippe; McCusker, Jane; Monette, Johanne; Savoie, Maryse; Richard, Sylvie; Carmichael, Pierre-Hugues (2015). "Recognizing acute delirium as part of your routine [RADAR]: a validation study". BMC Nursing. 14: 19. doi: 10.1186/s12912-015-0070-1 . ISSN 1472-6955. PMC 4384313 . PMID 25844067.

- ↑ Schuurmans, Marieke J.; Shortridge-Baggett, Lillie M.; Duursma, Sijmen A. (2003). "The Delirium Observation Screening Scale: a screening instrument for delirium". Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 17 (1): 31–50. doi:10.1891/rtnp.17.1.31.53169. ISSN 1541-6577. PMID 12751884. S2CID 219203272.

- ↑ Sands, M. B.; Dantoc, B. P.; Hartshorn, A.; Ryan, C. J.; Lujic, S. (September 2010). "Single Question in Delirium (SQiD): testing its efficacy against psychiatrist interview, the Confusion Assessment Method and the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale". Palliative Medicine. 24 (6): 561–565. doi:10.1177/0269216310371556. ISSN 1477-030X. PMID 20837733. S2CID 40306973.

- ↑ Hargrave, Anita; Bastiaens, Jesse; Bourgeois, James A.; Neuhaus, John; Josephson, S. Andrew; Chinn, Julia; Lee, Melissa; Leung, Jacqueline; Douglas, Vanja (November 2017). "Validation of a Nurse-Based Delirium-Screening Tool for Hospitalized Patients". Psychosomatics. 58 (6): 594–603. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2017.05.005. ISSN 1545-7206. PMC 5798858 . PMID 28750835.

- ↑ "Delirium detection in routine clinical care: two basic processes". DeliriumWords.com. 15 June 2020. Retrieved 2021-01-12.

- ↑ "A classification of delirium assessment tools". DeliriumWords.com. 13 July 2020. Retrieved 2020-11-28.

- ↑ De, J; Wand, AP (December 2015). "Delirium Screening: A Systematic Review of Delirium Screening Tools in Hospitalized Patients". The Gerontologist. 55 (6): 1079–99. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv100 . PMID 26543179.

- ↑ Pérez-Ros, P; Martínez-Arnau, FM (30 January 2019). "Delirium Assessment in Older People in Emergency Departments. A Literature Review". Diseases. 7 (1): 14. doi: 10.3390/diseases7010014 . PMC 6473718 . PMID 30704024.

- ↑ Rieck, KM; Pagali, S; Miller, DM (March 2020). "Delirium in hospitalized older adults". Hospital Practice (1995). 48 (sup1): 3–16. doi:10.1080/21548331.2019.1709359. PMID 31874064. S2CID 209474088.

- ↑ "Adult Delirium Measurement Info Cards – NIDUS" . Retrieved 14 May 2020.