Related Research Articles

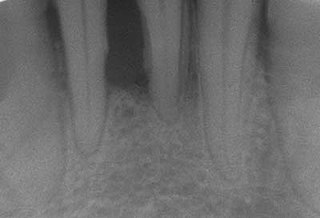

Periodontal disease, also known as gum disease, is a set of inflammatory conditions affecting the tissues surrounding the teeth. In its early stage, called gingivitis, the gums become swollen and red and may bleed. It is considered the main cause of tooth loss for adults worldwide. In its more serious form, called periodontitis, the gums can pull away from the tooth, bone can be lost, and the teeth may loosen or fall out. Bad breath may also occur.

The gums or gingiva consist of the mucosal tissue that lies over the mandible and maxilla inside the mouth. Gum health and disease can have an effect on general health.

The periodontal ligament, commonly abbreviated as the PDL, is a group of specialized connective tissue fibers that essentially attach a tooth to the alveolar bone within which it sits. It inserts into root cementum on one side and onto alveolar bone on the other.

Periodontology or periodontics is the specialty of dentistry that studies supporting structures of teeth, as well as diseases and conditions that affect them. The supporting tissues are known as the periodontium, which includes the gingiva (gums), alveolar bone, cementum, and the periodontal ligament. A periodontist is a dentist that specializes in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of periodontal disease and in the placement of dental implants.

Veterinary dentistry is the field of dentistry applied to the care of animals. It is the art and science of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of conditions, diseases, and disorders of the oral cavity, the maxillofacial region, and its associated structures as it relates to animals.

The gingival sulcus is an area of potential space between a tooth and the surrounding gingival tissue and is lined by sulcular epithelium. The depth of the sulcus is bounded by two entities: apically by the gingival fibers of the connective tissue attachment and coronally by the free gingival margin. A healthy sulcular depth is three millimeters or less, which is readily self-cleansable with a properly used toothbrush or the supplemental use of other oral hygiene aids.

Gingival and periodontal pockets are dental terms indicating the presence of an abnormal depth of the gingival sulcus near the point at which the gingival tissue contacts the tooth.

Scaling and root planing, also known as conventional periodontal therapy, non-surgical periodontal therapy or deep cleaning, is a procedure involving removal of dental plaque and calculus and then smoothing, or planing, of the (exposed) surfaces of the roots, removing cementum or dentine that is impregnated with calculus, toxins, or microorganisms, the agents that cause inflammation. It is a part of non-surgical periodontal therapy. This helps to establish a periodontium that is in remission of periodontal disease. Periodontal scalers and periodontal curettes are some of the tools involved.

Gingivectomy is a dental procedure in which a dentist or oral surgeon cuts away part of the gums in the mouth.

Laser-assisted new attachment procedure (LANAP) is a surgical therapy for the treatment of periodontitis, intended to work through regeneration rather than resection. This therapy and the laser used to perform it have been in use since 1994. It was developed by Robert H. Gregg II and Delwin McCarthy.

Guided bone regeneration (GBR) and guided tissue regeneration (GTR) are dental surgical procedures that use barrier membranes to direct the growth of new bone and gingival tissue at sites with insufficient volumes or dimensions of bone or gingiva for proper function, esthetics or prosthetic restoration. Guided bone regeneration typically refers to ridge augmentation or bone regenerative procedures; guided tissue regeneration typically refers to regeneration of periodontal attachment.

Gingivitis is a non-destructive disease that causes inflammation of the gums; ulitis is an alternative term. The most common form of gingivitis, and the most common form of periodontal disease overall, is in response to bacterial biofilms that are attached to tooth surfaces, termed plaque-induced gingivitis. Most forms of gingivitis are plaque-induced.

In dentistry, debridement refers to the removal by dental cleaning of accumulations of plaque and calculus (tartar) in order to maintain dental health. Debridement may be performed using ultrasonic instruments, which fracture the calculus, thereby facilitating its removal, as well as hand tools, including periodontal scaler and curettes, or through the use of chemicals such as hydrogen peroxide.

Epidemiology of periodontal disease is the study of patterns, causes, and effects of periodontal diseases. Periodontal disease is a disease affecting the tissue surrounding the teeth. This causes the gums and the teeth to separate making spaces that become infected. The immune system tries to fight the toxins breaking down the bone and tissue connecting to the teeth to the gums. The teeth will have to be removed. This is an advance stage of gum disease that has multiple definitions. Adult periodontitis affects less than 10 to 15% of the population in industrialized countries, mainly adults around the ages of 50 to 60. The disease is now declining world-wide.

Chronic periodontitis is one of the seven categories of periodontitis as defined by the American Academy of Periodontology 1999 classification system. Chronic periodontitis is a common disease of the oral cavity consisting of chronic inflammation of the periodontal tissues that is caused by the accumulation of profuse amounts of dental plaque. Periodontitis initially begins as gingivitis and can progress onto chronic and subsequent aggressive periodontitis according to the 1999 classification.

Peri-implantitis is a destructive inflammatory process affecting the soft and hard tissues surrounding dental implants. The soft tissues become inflamed whereas the alveolar bone, which surrounds the implant for the purposes of retention, is lost over time.

In dentistry, numerous types of classification schemes have been developed to describe the teeth and gum tissue in a way that categorizes various defects. All of these classification schemes combine to provide the periodontal diagnosis of the aforementioned tissues in their various states of health and disease.

Tooth mobility is the horizontal or vertical displacement of a tooth beyond its normal physiological boundaries around the gingival area, i.e. the medical term for a loose tooth.

Periodontal surgery is a form of dental surgery that prevents or corrects anatomical, traumatic, developmental, or plaque-induced defects in the bone, gingiva, or alveolar mucosa. The objectives of this surgery include accessibility of instruments to root surface, elimination of inflammation, creation of an oral environment for plaque control, periodontal diseases control, oral hygiene maintenance, maintain proper embrasure space, address gingiva-alveolar mucosa problems, and esthetic improvement. The surgical procedures include crown lengthening, frenectomy, and mucogingival flap surgery.

References

- 1 2 Armitage GC (December 1999). "Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions". Annals of Periodontology. 4 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. PMID 10863370.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Joshipura V, Yadalam U, Brahmavar B (2015-01-01). "Aggressive periodontitis: A review". Journal of the International Clinical Dental Research Organization. 7 (1): 11. doi: 10.4103/2231-0754.153489 .

- 1 2 Clerehugh V (2012). "Guidelines for periodontal screening and management of children and adolescents under 18 years of age" (PDF). British Society of Periodontology and The British Society of Paediatric Dentistry. Retrieved 6 Dec 2017.

- ↑ Albandar JM, Tinoco EM (2002). "Global epidemiology of periodontal diseases in children and young persons". Periodontol. 2000. 29: 153–76. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.290108.x. PMID 12102707.[ verification needed ]

- ↑ Papapanou PN (November 1996). "Periodontal diseases: epidemiology". Ann. Periodontol. 1 (1): 1–36. doi:10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.1. PMID 9118256.[ verification needed ]

- ↑ Needleman I (2016). "The Good Practitioner's Guide to Periodontology" (PDF). British Society of Periodontology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 6 Dec 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Whiley RA (2006-11-25). "Essential microbiology for dentistry". British Dental Journal (3rd ed.). 201 (10): 679. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4814299 .

- ↑ Zambon JJ, Christersson LA, Slots J (December 1983). "Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in human periodontal disease. Prevalence in patient groups and distribution of biotypes and serotypes within families". Journal of Periodontology. 54 (12): 707–11. doi:10.1902/jop.1983.54.12.707. PMID 6358452. S2CID 27904962.

- 1 2 Fives-Taylor PM, Meyer DH, Mintz KP, Brissette C (June 1999). "Virulence factors of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans". Periodontology 2000. 20: 136–67. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0757.1999.tb00161.x. PMID 10522226.

- 1 2 Thiha K, Takeuchi Y, Umeda M, Huang Y, Ohnishi M, Ishikawa I (June 2007). "Identification of periodontopathic bacteria in gingival tissue of Japanese periodontitis patients". Oral Microbiology and Immunology. 22 (3): 201–7. doi:10.1111/j.1399-302X.2007.00354.x. PMID 17488447.

- 1 2 Nonnenmacher C, Mutters R, de Jacoby LF (April 2001). "Microbiological characteristics of subgingival microbiota in adult periodontitis, localized juvenile periodontitis and rapidly progressive periodontitis subjects". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 7 (4): 213–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2001.00210.x . PMID 11422244.

- ↑ Genco RJ, Zambon JJ, Christersson LA (November 1986). "Use and interpretation of microbiological assays in periodontal diseases". Oral Microbiology and Immunology. 1 (1): 73–81. doi:10.1111/j.1399-302X.1986.tb00324.x. PMID 3295682.

- 1 2 3 Wilson TG, Kornman KS (2003). fundamentals of periodontics (2nd ed.). Quintessence Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-86715-405-4.[ page needed ]

- ↑ Garcia, Monique; Cappelli, David. "UTCAT2409, Found CAT view, CRITICALLY APPRAISED TOPICs". cats.uthscsa.edu. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ↑ Kinane DF, Hart TC (2003). "Genes and gene polymorphisms associated with periodontal disease". Critical Reviews in Oral Biology and Medicine. 14 (6): 430–49. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400605 . PMID 14656898.

- ↑ Schenkein HA, Gunsolley JC, Koertge TE, Schenkein JG, Tew JG (August 1995). "Smoking and its effects on early-onset periodontitis". Journal of the American Dental Association. 126 (8): 1107–13. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1995.0327. PMID 7560567.

- 1 2 "1999 International International Workshop for a Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions. Papers. Oak Brook, Illinois, October 30-November 2, 1999". Annals of Periodontology. 4 (1): i, 1–112. December 1999. doi:10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.i. PMID 10896458.

- ↑ Ramachandra, Srinivas Sulugodu; Gupta, Vivek Vijay; Mehta, Dhoom Singh; Gundavarapu, Kalyan C; Luigi, Nibali (2017). "Differential Diagnosis between Chronic versus Aggressive Periodontitis and Staging of Aggressive Periodontitis: A Cross-sectional Study". Contemporary Clinical Dentistry. 8 (4): 594–603. doi: 10.4103/ccd.ccd_623_17 . PMC 5754981 . PMID 29326511.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Armitage, Gary C. (February 2004). "Periodontal diagnoses and classification of periodontal diseases". Periodontology 2000. 34 (1): 9–21. doi:10.1046/j.0906-6713.2002.003421.x. PMID 14717852.

- 1 2 Lang N, Bartold PM, Cullinan M, Jeffcoat M, Mombelli A, Murakami S, et al. (December 1999). "Consensus Report: Aggressive Periodontitis". Annals of Periodontology. 4 (1): 53. doi:10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.53.

- ↑ Bronstein, Diana; Kravchenko, Dmitriy; Suzuki, Jon B. (September 2016). "Managing Aggressive Periodontitis". Decisions in Dentistry. 2 (9): 46–49.

- ↑ Preshaw PM, Alba AL, Herrera D, Jepsen S, Konstantinidis A, Makrilakis K, Taylor R (January 2012). "Periodontitis and diabetes: a two-way relationship". Diabetologia. 55 (1): 21–31. doi:10.1007/s00125-011-2342-y. PMC 3228943 . PMID 22057194.

- ↑ "Periodontitis, aggressive". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ↑ Armitage GC (2004). "The complete periodontal examination". Periodontology 2000. 34: 22–33. doi:10.1046/j.0906-6713.2002.003422.x. PMID 14717853.

- 1 2 Ramachandra, SS; Dopico, J; Donos, N; Nibali, L (1 September 2017). "Disease Staging Index for Aggressive Periodontitis". Oral Health and Preventive Dentistry. 15 (4): 371–378. doi:10.3290/j.ohpd.a38746. PMID 28831460.

- 1 2 Vieira AR, Albandar JM (June 2014). "Role of genetic factors in the pathogenesis of aggressive periodontitis". Periodontology 2000. 65 (1): 92–106. doi:10.1111/prd.12021. PMID 24738588.

- ↑ Schaeken MJ, Creugers TJ, Van der Hoeven JS (September 1987). "Relationship between dental plaque indices and bacteria in dental plaque and those in saliva". Journal of Dental Research. 66 (9): 1499–502. doi:10.1177/00220345870660091701. PMID 3476622. S2CID 38972315.

- ↑ Fredman G, Oh SF, Ayilavarapu S, Hasturk H, Serhan CN, Van Dyke TE (2011). "Impaired phagocytosis in localized aggressive periodontitis: rescue by Resolvin E1". PLOS ONE. 6 (9): e24422. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...624422F. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024422 . PMC 3173372 . PMID 21935407.

- ↑ Shaddox L, Wiedey J, Bimstein E, Magnuson I, Clare-Salzler M, Aukhil I, Wallet SM (February 2010). "Hyper-responsive phenotype in localized aggressive periodontitis". Journal of Dental Research. 89 (2): 143–8. doi:10.1177/0022034509353397. PMC 3096871 . PMID 20042739.

- ↑ Asano, Masahiro; Asahara, Yoji; Kirino, Akinori; Ohishi, Mika; Akimaru, Noriko; Hama, Hideki; Sury, Yono; Shionoya, Akemi; Kido, Jun-ichi; Nagata, Toshihiko (2003). "思春期後に歯槽骨吸収が自然停止した早期発症型歯周炎患者の1症例" [Case Report of an Early-onset Periodontitis Patient Showing Self-Arrest of Alveolar Bone Loss after Puberty]. Nihon Shishubyo Gakkai Kaishi (Journal of the Japanese Society of Periodontology) (in Japanese). 45 (3): 279–288. doi: 10.2329/perio.45.279 .

- ↑ Fine, D. H.; Goldberg, D.; Karol, R. (April 1984). "Caries Levels in Patients With Juvenile Periodontitis". Journal of Periodontology. 55 (4): 242–246. doi:10.1902/jop.1984.55.4.242. PMID 6585543.

- ↑ Sulugodu Ramachandra, Srinivas (April 2014). "Low levels of caries in aggressive periodontitis: A literature review". The Saudi Dental Journal. 26 (2): 47–49. doi:10.1016/j.sdentj.2013.12.002. PMC 4229677 . PMID 25408595.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Albandar JM (June 2014). "Aggressive periodontitis: case definition and diagnostic criteria". Periodontology 2000. 65 (1): 13–26. doi:10.1111/prd.12014. PMID 24738584.

- 1 2 3 4 Albandar JM (June 2014). "Aggressive and acute periodontal diseases". Periodontology 2000. 65 (1): 7–12. doi:10.1111/prd.12013. PMID 24738583.

- 1 2 3 Armitage GC, Cullinan MP (June 2010). "Comparison of the clinical features of chronic and aggressive periodontitis". Periodontology 2000. 53: 12–27. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0757.2010.00353.x. PMID 20403102.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kebschull, Moritz; Dommisch, Henrik (17 July 2018). "Aggressive Periodontitis". Newman and Carranza's Clinical Periodontology. Elsevier. pp. 352–360.e4. ISBN 978-0-323-52300-4.

- ↑ Ramachandra, Srinivas Sulugodu; Hegde, Manjunath; Prasad, Umesh Chandra (2 June 2012). "Gingival enlargement and mesiodens associated with generalized aggressive periodontitis: a case report". Dental Update. 39 (5): 364–369. doi:10.12968/denu.2012.39.5.364. PMID 22852514.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Roshna T, Nandakumar K (2012). "Generalized aggressive periodontitis and its treatment options: case reports and review of the literature". Case Reports in Medicine. 2012: 535321. doi: 10.1155/2012/535321 . PMC 3265097 . PMID 22291715.

- ↑ Highfield J (September 2009). "Diagnosis and classification of periodontal disease". Australian Dental Journal. 54 (Suppl 1): S11-26. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01140.x . PMID 19737262.

- 1 2 3 Preshaw PM (2015-09-15). "Detection and diagnosis of periodontal conditions amenable to prevention". BMC Oral Health. 15 (Suppl 1): S5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-15-S1-S5 . PMC 4580822 . PMID 26390822.

- ↑ Clerehugh V, Kindelan S (2012). "Guidelines for Periodontal Screening and Management of Children and Adolescents Under 18 Years of Age" (PDF). British Society of Periodontology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-25. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ↑ Jonasson G (July 2015). "Five-year alveolar bone level changes in women of varying skeletal bone mineral density and bone trabeculation". Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology. 120 (1): 86–93. doi:10.1016/j.oooo.2015.04.009. PMID 26093684.

- ↑ Melnick M, Shields ED, Bixler D (July 1976). "Periodontosis: a phenotypic and genetic analysis". Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology. 42 (1): 32–41. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(76)90029-3. PMID 1065840.

- ↑ Nibali L, Donos N, Brett PM, Parkar M, Ellinas T, Llorente M, Griffiths GS (December 2008). "A familial analysis of aggressive periodontitis - clinical and genetic findings". Journal of Periodontal Research. 43 (6): 627–34. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0765.2007.01039.x. PMID 18752567.

- ↑ Llorente MA, Griffiths GS (February 2006). "Periodontal status among relatives of aggressive periodontitis patients and reliability of family history report". Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 33 (2): 121–5. doi:10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00887.x. PMID 16441736.

- 1 2 3 Teughels W, Dhondt R, Dekeyser C, Quirynen M (June 2014). "Treatment of aggressive periodontitis". Periodontology 2000. 65 (1): 107–33. doi:10.1111/prd.12020. PMID 24738589.

- ↑ Shahabuddin N, Boesze-Battaglia K, Lally ET (2016). "Trends in Susceptibility to Aggressive Periodontal Disease". International Journal of Dentistry and Oral Health. 2 (4). doi:10.16966/2378-7090.197. PMC 5172390 . PMID 28008419.

- ↑ Mullally BH, Breen B, Linden GJ (April 1999). "Smoking and patterns of bone loss in early-onset periodontitis". Journal of Periodontology. 70 (4): 394–401. doi:10.1902/jop.1999.70.4.394. PMID 10328651.

- ↑ (SDCEP), Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (June 2014). "Prevention and Treatment of Periodontal Diseases in Primary Care, Dental Clinical Guidance" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2021. Retrieved 7 Dec 2017.

- ↑ Aimetti M (2014). "Nonsurgical periodontal treatment". The International Journal of Esthetic Dentistry. 9 (2): 251–67. PMID 24765632.

- ↑ Keestra JA, Grosjean I, Coucke W, Quirynen M, Teughels W (December 2015). "Non-surgical periodontal therapy with systemic antibiotics in patients with untreated aggressive periodontitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Periodontal Research. 50 (6): 689–706. doi:10.1111/jre.12252. PMID 25522248.

- ↑ (BSP), British Society of Periodontology (Mar 2016). "The Good Practitioner's Guide to Periodontology" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 7 Dec 2017.

- ↑ Vohra F, Akram Z, Safii SH, Vaithilingam RD, Ghanem A, Sergis K, Javed F (March 2016). "Role of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in the treatment of aggressive periodontitis: A systematic review". Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy. 13: 139–147. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2015.06.010. PMID 26184762.

- ↑ Collins F. "Periodontal Treatment: The Delivery and Role of Locally Applied Therapeutics" (PDF). Retrieved 7 Dec 2017.

- ↑ Gupta, Vivek Vijay; Ramachandra, Srinivas Sulugodu (2019). "Aggressive periodontitis with a history of orthodontic treatment". Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology. 23 (4): 371–376. doi: 10.4103/jisp.jisp_654_18 . PMC 6628778 . PMID 31367137.

- ↑ Singh, R; Ramachandra, SS (August 2016). "Resective or Regenerative Periodontal Therapy: Considerations during Treatment Planning: A Case Report". The New York State Dental Journal. 82 (4): 46–49. PMID 30561962.

- ↑ Kamma JJ, Baehni PC (June 2003). "Five-year maintenance follow-up of early-onset periodontitis patients". Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 30 (6): 562–72. doi:10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00289.x. PMID 12795796.