Related Research Articles

The Royal Observer Corps (ROC) was a civil defence organisation intended for the visual detection, identification, tracking and reporting of aircraft over Great Britain. It operated in the United Kingdom between 29 October 1925 and 31 December 1995, when the Corps' civilian volunteers were stood down. Composed mainly of civilian spare-time volunteers, ROC personnel wore a Royal Air Force (RAF) style uniform and latterly came under the administrative control of RAF Strike Command and the operational control of the Home Office. Civilian volunteers were trained and administered by a small cadre of professional full-time officers under the command of the Commandant Royal Observer Corps; latterly a serving RAF Air Commodore.

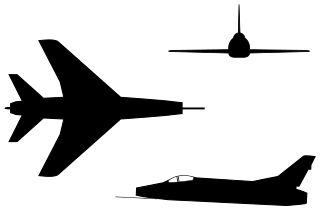

Aircraft recognition is a visual skill taught to military personnel and civilian auxiliaries since the introduction of military aircraft in World War I. It is important for air defense and military intelligence gathering.

The Ground Observer Corps (GOC), sometimes erroneously referred to as the Ground Observation Corps, was the name of two American civil defense organizations during the middle 20th century.

The Volunteer Air Observers Corps (VAOC) was an Australian air defence organisation of World War Two. The VAOC was formed in December 1941 to support the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) with its main roles of sighting and observing aircraft over Australia. The VAOC swiftly established thousands of Observation Posts (OP) across the country and provided information to the RAAF's regional air control posts.

The 104th Fighter Squadron, nicknamed the Fightin' O's, is a unit of the Maryland Air National Guard 175th Wing stationed at Warfield Air National Guard Base, Middle River, Maryland. The 104th is equipped with the Fairchild Republic A-10C Thunderbolt II.

The 102nd Rescue Squadron is a unit of the New York Air National Guard 106th Rescue Wing stationed at Francis S. Gabreski Air National Guard Base, Westhampton Beach, New York. The 102nd is equipped with the HC-130J Combat King II transport aircraft.

The 119th Fighter Squadron is a unit of the New Jersey Air National Guard 177th Fighter Wing located at Atlantic City Air National Guard Base, New Jersey. The 119th is equipped with the F-16 Fighting Falcon aircraft and is the oldest active flying fighter squadron in the Air National Guard.

The 3rd Special Operations Squadron flies MQ-9 Reaper Remotely Piloted Aircraft and is currently located at Cannon Air Force Base, New Mexico. The squadron is under the command of the Air Force Special Operations Command.

Roslyn Air National Guard Station is a closed United States Air Force station. It was located in East Hills, New York, on Long Island. It was originally part of Clarence MacKay's Harbor Hill estate. It was closed in 2000.

The Aircraft Warning Service Observation Tower in Agnew, Washington was built in 1941 as a spotting station for Aircraft Warning Service volunteers watching for intruding Japanese airplanes during World War II. The tower's original site was near Dungeness, but in 1992 the tower was moved to its present location.

The 123d Fighter Squadron is a unit of the Oregon Air National Guard 142d Fighter Wing located at Portland Air National Guard Base, Oregon. The 123d is equipped with the McDonnell Douglas F-15C Eagle.

The Aircraft Warning Corps (AWC) was a World War II United States Army Air Force organization for Continental United States air defense. The corps' information centers networked an area's "Army Radar Stations" which communicated radar tracks by telephone, and the information centers also integrated visual reports processed by Ground Observer Corps filter centers. The AWC notified air defense command posts of the First Air Force, Second Air Force, Third Air Force, and Fourth Air Force. These command posts would deploy interceptors which used command guidance to achieve ground-controlled interception.

Marine Air Control Squadron 7 (MACS-7) was a United States Marine Corps aviation command and control squadron. The squadron provided aerial surveillance and ground-controlled interception and saw action most notably during the Battle of Okinawa in World War II and the Vietnam War. They were last based at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma and fell under the command of Marine Air Control Group 38 (MACG-38) and the 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing.

Air Warning Squadron 2 (AWS-2) was a United States Marine Corps aviation command and control squadron during World War II. The squadron was tasked to provide aerial surveillance and early warning during amphibious assaults. They took part in the Battle of Guam in 1944 and would eventually move to Peleliu in 1945 assuming responsibility for air defense in that sector until the end of the war. The squadron departed Peleliu for the United States in January 1946 and was quickly decommissioned upon its arrival in California. To date, no other Marine Corps squadron has carried the lineage and honors of AWS-2 to include Marine Air Control Squadron 2 (MACS-2).

Air Warning Squadron 6 (AWS-6) was a United States Marine Corps aviation command and control unit that provided aerial surveillance and early warning of enemy aircraft during World War II. The squadron was activated on January 1, 1944 and was one of five Marine Air Warning Squadrons that provided land based radar coverage during the Battle of Okinawa in 1945. AWS-6 remained on Okinawa as part of the garrison force following the Surrender of Japan. The squadron departed Okinawa for the United States in February 1946 and was quickly decommissioned upon its arrival in California. To date, no other Marine Corps squadron has carried the lineage and honors of AWS-6 to include Marine Air Control Squadron 6 (MACS-6).

Air Warning Squadron 3 (AWS-3) was a United States Marine Corps aviation command and control squadron during World War II. The squadron's primary mission was to provide aerial surveillance and early warning of approaching enemy aircraft during amphibious assaults. The squadron participated in the Philippines campaign (1944–1945) in support of the Eighth Army on Mindanao. AWS-3 was decommissioned shortly after the war in October 1945 at Marine Corps Air Station Miramar, California. To date, no other Marine Corps squadron has carried the lineage and honors of AWS-3 to include the former Marine Air Control Squadron 3 (MACS-3).

Assault Air Warning Squadrons were United States Marine Corps aviation command and control units formed during World War II to provide early warning, aerial surveillance, and ground controlled interception during the early phases of amphibious landing. These squadrons were supposed to be fielded lightweight radars and control center gear in order to operate for a limited duration at the beginning of any operation until larger air warning squadrons came ashore. Four of these squadrons were commissioned during the war with one, AWS(AT)-5, taking part in the Battle of Saipan. All four squadrons were decommissioned on November 10, 1944 because the Marine Corps was unable to field the required mobile radars. The "first in" capability that the Assault Air Warning Squadrons were supposed to provide was transferred to the Early Warning Teams that were added to the tables of organization for the regular air warning squadrons.

Air Warning Squadron 4 (AWS-4) was a United States Marine Corps aviation command and control squadron during World War II. The squadron's primary mission was to provide aerial surveillance and early warning of approaching enemy aircraft during amphibious assaults. The squadron participated in the Philippines campaign (1944–1945) in support of the Eighth Army on Mindanao. AWS-4 was decommissioned shortly after the war in October 1945. To date, no other Marine Corps squadron has carried the lineage and honors of AWS-4 to include Marine Air Control Squadron 4 (MACS-4).

The VMF(N)-531 GCI Detachment was a short-lived aviation command and control unit that was part of the United States Marine Corps's first night fighter squadron, VMF(N)-531. This detachment was the Marine Corps' first dedicated GCI detachment utilized in a combat zone. In the early phases of World War II the Marine Corps did not have stand-alone early warning and ground-controlled intercept (GCI) units so these capabilities were initially placed in the headquarters of each Marine Aircraft Group and with individual night fighter squadrons. The detachment was deployed in the South Pacific from August 1943 through August 1944 and was responsible for the interception of numerous Japanese aircraft. Lessons learned from this deployment were instrumental in establishing tactics and procedures for the Marine Corps' newly established Air Warning Program. Upon returning from its first and only deployment, the detachment was dissolved and its members went on to serve as instructors at the 1st Marine Air Warning Group, which was responsible for training new squadrons. Many of them later served in leadership roles in these Air Warning Squadrons as they supported follow on combat operations.

References

- 1 2 3 Aircraft Warning Service Volunteer, June 1944

- ↑ Personal collection of Larry Frederick

- ↑ The Digital Deli, Eyes, Aloft!

- ↑ Letter from Henry L. Stimson, March 31, 1944

- ↑ Letter from Col. Stewart W. Towle, Jr. May 27, 1944.

- ↑ "The Hebron Historical Society of Hebron Connecticut". hebronhistoricalsociety.org. Retrieved 2017-02-11.