Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) is a rare autoimmune disorder characterized by muscle weakness of the limbs.

Neuromyotonia (NMT) is a form of peripheral nerve hyperexcitability that causes spontaneous muscular activity resulting from repetitive motor unit action potentials of peripheral origin. NMT along with Morvan's syndrome are the most severe types in the Peripheral Nerve Hyperexciteability spectrum. Example of two more common and less severe syndromes in the spectrum are Cramp Fasciculation Syndrome and Benign Fasciculation Syndrome. NMT can have both hereditary and acquired forms. The prevalence of NMT is unknown.

Morvan's syndrome is a rare, life-threatening autoimmune disease named after the nineteenth century French physician Augustin Marie Morvan. "La chorée fibrillaire" was first coined by Morvan in 1890 when describing patients with multiple, irregular contractions of the long muscles, cramping, weakness, pruritus, hyperhidrosis, insomnia and delirium. It normally presents with a slow insidious onset over months to years. Approximately 90% of cases spontaneously go into remission, while the other 10% of cases lead to death.

Opsoclonus myoclonus syndrome (OMS), also known as opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia (OMA), is a rare neurological disorder of unknown cause which appears to be the result of an autoimmune process involving the nervous system. It is an extremely rare condition, affecting as few as 1 in 10,000,000 people per year. It affects 2 to 3% of children with neuroblastoma and has been reported to occur with celiac disease and diseases of neurologic and autonomic dysfunction.

Rituximab, sold under the brand name Rituxan among others, is a monoclonal antibody medication used to treat certain autoimmune diseases and types of cancer. It is used for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, pemphigus vulgaris, myasthenia gravis and Epstein–Barr virus-positive mucocutaneous ulcers. It is given by slow intravenous infusion. Biosimilars of Rituxan include Blitzima, Riabni, Ritemvia, Rituenza, Rixathon, Ruxience, and Truxima.

Stiff-person syndrome (SPS), also known as stiff-man syndrome, is a rare neurologic disorder of unclear cause characterized by progressive muscular rigidity and stiffness. The stiffness primarily affects the truncal muscles and is superimposed by spasms, resulting in postural deformities. Chronic pain, impaired mobility, and lumbar hyperlordosis are common symptoms.

Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration (PCD) is a paraneoplastic syndrome associated with a broad variety of tumors including lung cancer, ovarian cancer, breast cancer, Hodgkin’s lymphoma and others. PCD is a rare condition that occurs in less than 1% of cancer patients.

Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), or non-small-cell lung carcinoma, is any type of epithelial lung cancer other than small-cell lung cancer (SCLC). NSCLC accounts for about 85% of all lung cancers. As a class, NSCLCs are relatively insensitive to chemotherapy, compared to small-cell carcinoma. When possible, they are primarily treated by surgical resection with curative intent, although chemotherapy has been used increasingly both preoperatively and postoperatively.

Hashimoto's encephalopathy, also known as steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis (SREAT), is a neurological condition characterized by encephalopathy, thyroid autoimmunity, and good clinical response to corticosteroids. It is associated with Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and was first described in 1966. It is sometimes referred to as a neuroendocrine disorder, although the condition's relationship to the endocrine system is widely disputed. It is recognized as a rare disease by the NIH Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center.

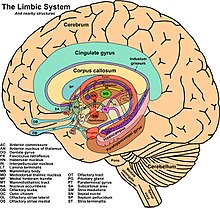

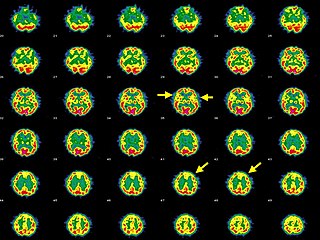

Limbic encephalitis is a form of encephalitis, a disease characterized by inflammation of the brain. Limbic encephalitis is caused by autoimmunity: an abnormal state where the body produces antibodies against itself. Some cases are associated with cancer and some are not. Although the disease is known as "limbic" encephalitis, it is seldom limited to the limbic system and post-mortem studies usually show involvement of other parts of the brain. The disease was first described by Brierley and others in 1960 as a series of three cases. The link to cancer was first noted in 1968 and confirmed by later investigators.

A paraneoplastic syndrome is a syndrome that is the consequence of a tumor in the body. It is specifically due to the production of chemical signaling molecules by tumor cells or by an immune response against the tumor. Unlike a mass effect, it is not due to the local presence of cancer cells.

Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) is a rapid-onset muscle weakness caused by the immune system damaging the peripheral nervous system. Typically, both sides of the body are involved, and the initial symptoms are changes in sensation or pain often in the back along with muscle weakness, beginning in the feet and hands, often spreading to the arms and upper body. The symptoms may develop over hours to a few weeks. During the acute phase, the disorder can be life-threatening, with about 15% of people developing weakness of the breathing muscles and, therefore, requiring mechanical ventilation. Some are affected by changes in the function of the autonomic nervous system, which can lead to dangerous abnormalities in heart rate and blood pressure.

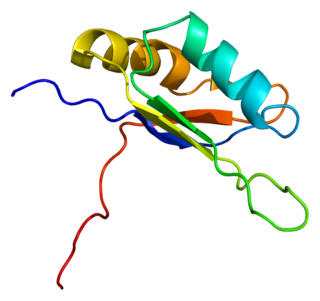

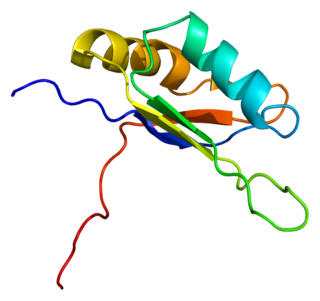

ELAV-like protein 3 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ELAVL3 gene.

Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis is a type of brain inflammation caused by antibodies. Early symptoms may include fever, headache, and feeling tired. This is then typically followed by psychosis which presents with false beliefs (delusions) and seeing or hearing things that others do not see or hear (hallucinations). People are also often agitated or confused. Over time, seizures, decreased breathing, and blood pressure and heart rate variability typically occur. In some cases, patients may develop catatonia.

Bickerstaff brainstem encephalitis is a rare inflammatory disorder of the central nervous system, first described by Edwin Bickerstaff in 1951. It may also affect the peripheral nervous system, and has features in common with both Miller Fisher syndrome and Guillain–Barré syndrome.

Targeted molecular therapy for neuroblastoma involves treatment aimed at molecular targets that have a unique expression in this form of cancer. Neuroblastoma, the second most common pediatric malignant tumor, often involves treatment through intensive chemotherapy. A number of molecular targets have been identified for the treatment of high-risk forms of this disease. Aiming treatment in this way provides a more selective way to treat the disease, decreasing the risk for toxicities that are associated with the typical treatment regimen. Treatment using these targets can supplement or replace some of the intensive chemotherapy that is used for neuroblastoma. These molecular targets of this disease include GD2, ALK, and CD133. GD2 is a target of immunotherapy, and is the most fully developed of these treatment methods, but is also associated with toxicities. ALK has more recently been discovered, and drugs in development for this target are proving to be successful in neuroblastoma treatment. The role of CD133 in neuroblastoma has also been more recently discovered and is an effective target for treatment of this disease.

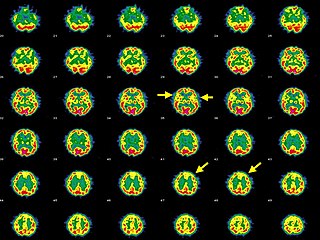

Autoimmune encephalitis (AIE) is a type of encephalitis, and one of the most common causes of noninfectious encephalitis. It can be triggered by tumors, infections, or it may be cryptogenic. The neurological manifestations can be either acute or subacute and usually develop within six weeks. The clinical manifestations include behavioral and psychiatric symptoms, autonomic disturbances, movement disorders, and seizures.

Autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy is a type of immune-mediated autonomic failure that is associated with antibodies against the ganglionic nicotinic acetylcholine receptor present in sympathetic, parasympathetic, and enteric ganglia. Typical symptoms include gastrointestinal dysmotility, orthostatic hypotension, and tonic pupils. Many cases have a sudden onset, but others worsen over time, resembling degenerative forms of autonomic dysfunction. For milder cases, supportive treatment is used to manage symptoms. Plasma exchange, intravenous immunoglobulin, corticosteroids, or immunosuppression have been used successfully to treat more severe cases.

Autoimmune retinopathy (AIR) is a rare disease in which the patient's immune system attacks proteins in the retina, leading to loss of eyesight. The disease is poorly understood, but may be the result of cancer or cancer chemotherapy. The disease is an autoimmune condition characterized by vision loss, blind spots, and visual field abnormalities. It can be divided into cancer-associated retinopathy (CAR) and melanoma-associated retinopathy (MAR). The condition is associated with retinal degeneration caused by autoimmune antibodies recognizing retinal proteins as antigens and targeting them. AIR's prevalence is extremely rare, with CAR being more common than MAR. It is more commonly diagnosed in females in the age range of 50–60.

Anti-VGKC-complex encephalitis are caused by antibodies against the voltage gated potassium channel-complex (VGKC-complex) and are implicated in several autoimmune conditions including limbic encephalitis, epilepsy and neuromyotonia.