The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation and the European Reformation, was a major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and the authority of the Catholic Church. Following the start of the Renaissance, the Reformation marked the beginning of Protestantism.

The relations between the Catholic Church and the state have been constantly evolving with various forms of government, some of them controversial in retrospect. In its history, the Church has had to deal with various concepts and systems of governance, from the Roman Empire to the medieval divine right of kings, from nineteenth- and twentieth-century concepts of democracy and pluralism to the appearance of left- and right-wing dictatorial regimes. The Second Vatican Council's decree Dignitatis humanae stated that religious freedom is a civil right that should be recognized in constitutional law.

The words Popery and Papism are mainly historical pejorative words in the English language for Roman Catholicism, once frequently used by Protestants and Eastern Orthodox Christians to label their Roman Catholic opponents, who differed from them in accepting the authority of the Pope over the Christian Church. The words were popularised during the English Reformation (1532–1559), when the Church of England broke away from the Roman Catholic Church and divisions emerged between those who rejected papal authority and those who continued to follow Rome. The words are recognised as pejorative; they have been in widespread use in Protestant writings until the mid-nineteenth century, including use in some laws that remain in force in the United Kingdom.

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics and opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and its adherents. At various points after the Reformation, some majority Protestant states, including England, Northern Ireland, Prussia, Scotland, and the United States, turned anti-Catholicism, opposition to the authority of Catholic clergy (anti-clericalism), opposition to the authority of the pope (anti-papalism), mockery of Catholic rituals, and opposition to Catholic adherents into major political themes and policies of religious discrimination and religious persecution. Major examples of groups that have targeted Catholics in recent history include Ulster loyalists in Northern Ireland during the Troubles and the second Ku Klux Klan in the United States. The anti-Catholic sentiment which resulted from this trend frequently led to religious discrimination against Catholic communities and individuals and it occasionally led to the religious persecution of them. Historian John Wolffe identifies four types of anti-Catholicism: constitutional-national, theological, popular and socio-cultural.

Christianity is the largest religion in Germany. It was introduced to the area of modern Germany by 300 AD, while parts of that area belonged to the Roman Empire, and later, when Franks and other Germanic tribes converted to Christianity from the fifth century onwards. The area became fully Christianized by the time of Charlemagne in the eighth and ninth century. After the Reformation started by Martin Luther in the early 16th century, many people left the Catholic Church and became Protestant, mainly Lutheran and Calvinist. In the 17th and 18th centuries, German cities also became hubs of heretical and sometimes anti-religious freethinking, challenging the influence of religion and contributing to the spread of secular thinking about morality across Germany and Europe.

The history of religion in the Netherlands has been characterized by considerable diversity of religious thought and practice. From 1600 until the second half of the 20th century, the north and west had embraced the Protestant Reformation and were Calvinist. The southeast was predominately Catholic. Associated with immigration from Arab world of the 20th century, Muslims and other minority religions were concentrated in ethnic neighborhoods in the cities.

Protestantism originated from the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century. The term Protestant comes from the Protestation at Speyer in 1529, where the nobility protested against enforcement of the Edict of Worms which subjected advocates of Lutheranism to forfeit of all their property. However, the theological underpinnings go back much further, as Protestant theologians of the time cited both Church Fathers and the Apostles to justify their choices and formulations. The earliest origin of Protestantism is controversial; with some Protestants today claiming origin back to people in the early church deemed heretical such as Jovinian and Vigilantius.

Ireland during the period of 1536–1691 saw the first full conquest of the island by England and its colonization with mostly Protestant settlers from Great Britain. This would eventually establish two central themes in future Irish history: subordination of the country to London-based governments and sectarian animosity between Catholics and Protestants. The period saw Irish society outside of the Pale transform from a locally driven, intertribal, clan-based Gaelic structure to a centralised, monarchical, state-governed society, similar to those found elsewhere in Europe. The period is bounded by the dates 1536, when King Henry VIII deposed the FitzGerald dynasty as Lords Deputies of Ireland, and 1691, when the Catholic Jacobites surrendered at Limerick, thus confirming Protestant dominance in Ireland. This is sometimes called the early modern period.

Religion in Austria is predominantly Christianity, adhered to by 68.2% of the country's population according to the 2021 national survey conducted by Statistics Austria. Among Christians, 80.9% were Catholics, 7.2% were Orthodox Christians, 5.6% were Protestants, while the remaining 6.2% were other Christians, belonging to other denominations of the religion or not affiliated to any denomination. In the same census, 8.3% of the Austrians declared that their religion was Islam, 1.2% declared to believe in other non-Christian religions, and 22.4% declared they did not belong to any religion, denomination or religious community.

Christianity is the largest religion in Europe. Christianity has been practiced in Europe since the first century, and a number of the Pauline Epistles were addressed to Christians living in Greece, as well as other parts of the Roman Empire.

Protestantism is the largest religious demographic in the United Kingdom.

Religion in Eritrea consists of a number of faiths. The two major religions in Eritrea are Christianity and Islam. However, the number of adherents of each faith is subject to debate. Estimates of the Christian share of the population range from 47% and 63%, while estimates of the Muslim share of the population range from 37% to 52%.

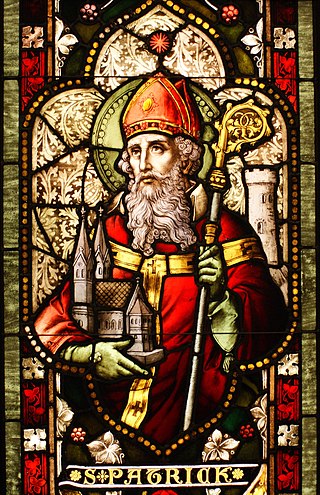

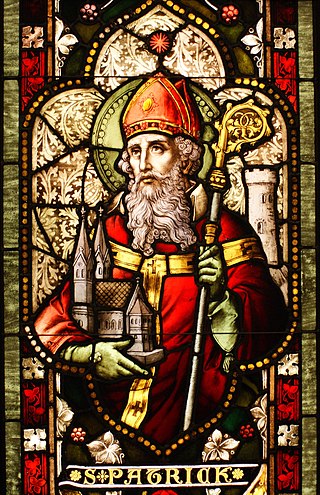

Christianity is, and has been the largest religion in Ireland since the 5th century. After a pagan past of Antiquity, missionaries, most famously including Saint Patrick, converted the Irish tribes to Christianity in quick order, producing a great number of saints in the Early Middle Ages, and a faith interwoven with Irish identity for centuries since − though less so in recent times.

Christianity was introduced to North America as it was colonized by Europeans beginning in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Spanish, French, and British brought Roman Catholicism to the colonies of New Spain, New France and Maryland respectively, while Northern European peoples introduced Protestantism to Massachusetts Bay Colony, New Netherland, Virginia colony, Carolina Colony, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Lower Canada. Among Protestants, adherents to Anglicanism, Methodism, the Baptist Church, Congregationalism, Presbyterianism, Lutheranism, Quakerism, Mennonite and the Moravian Church were the first to settle in the US, spreading their faith in the new country.

In 16th-century Christianity, Protestantism came to the forefront and marked a significant change in the Christian world.

Anti-Catholicism in the United Kingdom dates back to Roman times. Attacks on the Church from a Protestant angle mostly began with the English and Irish Reformations which were launched by King Henry VIII and the Scottish Reformation which was led by John Knox. Within England, the Act of Supremacy 1534 declared the English crown to be "the only supreme head on earth of the Church in England" in place of the Pope. Any act of allegiance to the latter was considered treasonous because the papacy claimed both spiritual and political power over its followers. Ireland was brought under direct English control starting in 1536 during the Tudor conquest of Ireland. The Scottish Reformation in 1560 abolished Catholic ecclesiastical structures and rendered Catholic practice illegal in Scotland. Today, anti-Catholicism remains common in the United Kingdom, with particular relevance in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

The history of modern Christianity concerns the Christian religion from the beginning of the 15th century to the end of World War II. It can be divided into the early modern period and the late modern period. The history of Christianity in the early modern period coincides with the Age of Exploration, and is usually taken to begin with the Protestant Reformation c. 1517–1525 and ending in the late 18th century with the onset of the Industrial Revolution and the events leading up to the French Revolution of 1789. It includes the Protestant Reformation, the Counter-Reformation and the Catholic Church and the Age of Discovery. Christianity expanded throughout the world during the Age of Exploration. Christianity has thus become the world's largest religion.

Sectarianism can be defined as a practice that is created over a period of time through consistent social, cultural and political habits leading to the formation of group solidarity that is dependent upon practices of inclusion and exclusion. Sectarian discrimination focuses on the exclusion aspect of sectarianism and can be defined as 'hatred arising from attaching importance to perceived differences between subdivisions within a group', for example the different denominations of a religion or the factions of a political belief.

Sectarian violence among Christians is a recurring phenomenon, in which Christians engage in a form of communal violence known as sectarian violence. This form of violence can frequently be attributed to differences of religious beliefs between sects of Christianity (sectarianism). Sectarian violence among Christians was common, especially during late antiquity, and the years surrounding the protestant reformation, in which a German monk who was named Martin Luther disputed some of the Catholic Church's practices; particularly the doctrine of Indulgences, and it was crucial in the formation of a new sect of Christianity known as Protestantism. During the latter half of the Renaissance was when sectarianism related violence was most common among Christians. Conflicts like the European wars of religion or Dutch Revolt ravaged Western Europe. In France there were the French Wars of Religion and in the United Kingdom anti-Catholic hate was heightened by the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. And while sectarian violence may seem like an archaic footnote today, sectarian violence among Christians still persists in the modern world with groups such as the Ku Klux Klan perpetuating violence among Catholics.

Catholic–Protestant relations refers to the social, political and theological relations and dialogue between the Catholics and Protestants.