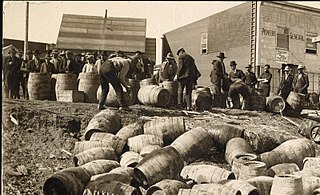

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage, transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic beverages. The word is also used to refer to a period of time during which such bans are enforced.

The Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution established the prohibition of alcohol in the United States. The amendment was proposed by Congress on December 18, 1917, and ratified by the requisite number of states on January 16, 1919. The Eighteenth Amendment was repealed by the Twenty-first Amendment on December 5, 1933—it is the only constitutional amendment in American history to be repealed.

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting temperance or complete abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and its leaders emphasize alcohol's negative effects on people's health, personalities and family lives. Typically the movement promotes alcohol education and it also demands the passage of new laws against the sale of alcohol, either regulations on the availability of alcohol, or the complete prohibition of it. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the temperance movement became prominent in many countries, particularly in English-speaking, Scandinavian, and majority Protestant ones, and it eventually led to national prohibitions in Canada, Norway, Finland, and the United States, as well as provincial prohibition in India. A number of temperance organizations exist that promote temperance and teetotalism as a virtue.

Westerville is a city in Franklin and Delaware counties in the U.S. state of Ohio. A northeastern suburb of Columbus as well as the home of Otterbein University, the population was 39,190 at the 2020 census.

Mary Hunt was an American activist in the United States temperance movement promoting total abstinence and prohibition of alcohol. She gained the power to accept or reject children's textbooks based on their representation of her views of the danger of alcohol. On her death there were questions asked regarding the finances of the organisation.

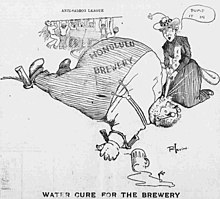

Ernest Hurst Cherrington was a leading temperance journalist. He became active in the Anti-Saloon League and was appointed editor of the organization's publishing house, the American Issue Publishing Company. He edited and contributed to the writing of The Standard Encyclopedia of the Alcohol Problem, a comprehensive six-volume work. In addition, he was active in establishing the World League Against Alcoholism.

Howard Hyde Russell was an American lawyer and clergyman, the founder of the Anti-Saloon League.

The World League Against Alcoholism (WLAA) was organized by the Anti-Saloon League, whose goal became establishing prohibition not only in the United States but throughout the entire world.

The American Issue Publishing Company, incorporated in 1909, was the holding company of the Anti-Saloon League of America. Its printing presses operated 24 hours a day and it employed 200 people in the small town of Westerville, Ohio, where the company had its headquarters. Within the first three years of its existence the publishing house was producing about 250,000,000 book pages per month, and the quantity increased yearly. This dwarfed the output of the National Temperance Society and Publishing House, which took over half a century to print one billion pages.

In the United States, the nationwide ban on alcoholic beverages, was repealed by the passage of the Twenty-first Amendment to the United States Constitution on December 5, 1933.

The Crusaders was an organization founded to promote the repeal of prohibition in the United States. The executive board consisted of fifty members, including Alfred Sloan, Jr., Sewell Avery, Cleveland Dodge, and Wallage Alexander. They wanted the government to create stronger laws regarding drunkenness.

The American Temperance Society (ATS), also known as the American Society for the Promotion of Temperance, was a society established on February 13, 1826, in Boston, Massachusetts. Within five years there were 2,220 local chapters in the U.S. with 170,000 members who had taken a pledge to abstain from drinking distilled beverages, though not including wine and beer; it permitted the medicinal use of alcohol as well. Within ten years, there were over 8,000 local groups and more than 1,250,000 members who had taken the pledge.

The Westerville Public Library is a public library that serves the community of Westerville, Ohio, a suburb of Columbus, Ohio. As a school district library, its geographic boundaries are defined by the Westerville City School District which is located in both Franklin County and Delaware County. All Ohio residents can apply for a Westerville Public Library card.

Wayne Bidwell Wheeler was an American attorney and longtime leader of the Anti-Saloon League. The leading advocate of the prohibitionist movement in the late 1800s and early 1900s, he played a major role in the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which outlawed the manufacture, distribution, and sale of alcoholic beverages.

The Prohibition era was the period from 1920 to 1933 when the United States prohibited the production, importation, transportation and sale of alcoholic beverages. The alcohol industry was curtailed by a succession of state legislatures, and finally ended nationwide under the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified on January 16, 1919. Prohibition ended with the ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment, which repealed the Eighteenth Amendment on December 5, 1933.

A dry state was a state in the United States in which the manufacture, distribution, importation, and sale of alcoholic beverages was prohibited or tightly restricted. Some states, such as North Dakota, entered the United States as dry states, and others went dry after the passage of prohibition legislation or the Volstead Act. No state remains completely dry, but some states do contain dry counties.

In the United States, the temperance movement, which sought to curb the consumption of alcohol, had a large influence on American politics and American society in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, culminating in the prohibition of alcohol, through the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, from 1920 to 1933. Today, there are organizations that continue to promote the cause of temperance.

The Temperance movement began over 40 years before the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was introduced. Across the country different groups began lobbying for temperance by arguing that alcohol was morally corrupting and hurting families economically, when men would drink their family's money away. This temperance movement paved the way for some women to join the Prohibition movement, which they often felt was necessary due to their personal experiences dealing with drunk husbands and fathers, and because it was one of the few ways for women to enter politics in the era. One of the most notable groups that pushed for Prohibition was the Woman's Christian Temperance Union. On the other end of the spectrum was the Women's Organization for National Prohibition Reform, who were instrumental in getting the 18th Amendment repealed. The latter organization argued that Prohibition was a breach of the rights of American citizens and frankly ineffective due to the prevalence of bootlegging.

Suessa Baldridge Blaine was an American writer of temperance pageants. She was connected with the Federated Woman's Clubs and organizations.