Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage, transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic beverages. The word is also used to refer to a period of time during which such bans are enforced.

The Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution established the prohibition of alcohol in the United States. The amendment was proposed by Congress on December 18, 1917, and ratified by the requisite number of states on January 16, 1919. The Eighteenth Amendment was repealed by the Twenty-first Amendment on December 5, 1933—it is the only constitutional amendment in American history to be repealed.

The Twenty-first Amendment to the United States Constitution repealed the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which had mandated nationwide prohibition on alcohol. The Twenty-first Amendment was proposed by the 72nd Congress on February 20, 1933, and was ratified by the requisite number of states on December 5, 1933. It is unique among the 27 amendments of the U.S. Constitution for being the only one to repeal a prior amendment, as well as being the only amendment to have been ratified by state ratifying conventions.

The Blaine Act, formally titled Joint Resolution Proposing the Twenty-First Amendment to the United States Constitution, is a joint resolution adopted by the United States Congress on February 20, 1933, initiating repeal of the 18th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which established Prohibition in the United States. Repeal was finalized when the 21st Amendment to the Constitution was ratified by the required minimum number of states on December 5, 1933.

The Bureau of Prohibition was the United States federal law enforcement agency formed to enforce the National Prohibition Act of 1919, commonly known as the Volstead Act, which enforced the 18th Amendment to the United States Constitution regarding the prohibition of the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcoholic beverages. When it was first established in 1920, it was a unit of the Bureau of Internal Revenue. On April 1, 1927, it became an independent entity within the Department of the Treasury, changing its name from the Prohibition Unit to the Bureau of Prohibition. In 1930, it became part of the Department of Justice. By 1933, with the repeal of Prohibition imminent, it was briefly absorbed into the FBI, or "Bureau of Investigation" as it was then called, and became the Bureau's "Alcohol Beverage Unit," though, for practical purposes it continued to operate as a separate agency. Very shortly after that, once repeal became a reality, and the only federal laws regarding alcoholic beverages being their taxation, it was switched back to Treasury, where it was renamed the Alcohol Tax Unit.

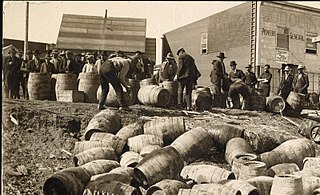

Rum-running, or bootlegging, is the illegal business of smuggling alcoholic beverages where such transportation is forbidden by law. Smuggling usually takes place to circumvent taxation or prohibition laws within a particular jurisdiction. The term rum-running is more commonly applied to smuggling over water; bootlegging is applied to smuggling over land.

In the United States, the nationwide ban on alcoholic beverages, was repealed by the passage of the Twenty-first Amendment to the United States Constitution on December 5, 1933.

Wayne Bidwell Wheeler was an American attorney and longtime leader of the Anti-Saloon League. The leading advocate of the prohibitionist movement in the late 1800s and early 1900s, he played a major role in the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which outlawed the manufacture, distribution, and sale of alcoholic beverages.

The Webb–Kenyon Act was a 1913 law of the United States that regulated the interstate transport of alcoholic beverages. It was meant to provide federal support for the prohibition efforts of individual states in the face of charges that state regulation of alcohol usurped the federal government's exclusive constitutional right to regulate interstate commerce.

The alcohol laws of Kansas are among the strictest in the United States, in sharp contrast to its neighboring state of Missouri, and similar to its other neighboring state of Oklahoma. Legislation is enforced by the Kansas Division of Alcoholic Beverage Control.

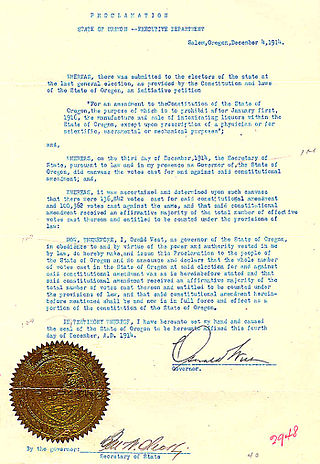

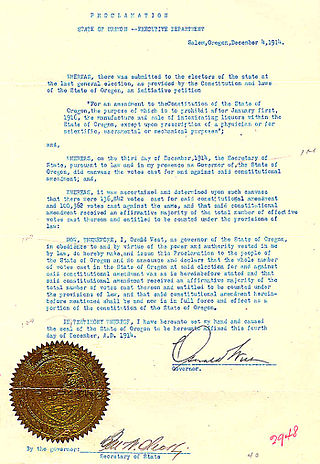

The U.S. state of Oregon has an extensive history of laws regulating the sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages, dating back to 1844. It has been an alcoholic beverage control state, with the Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission holding a monopoly over the sale of all distilled beverages, since Prohibition. Today, there are thriving industries producing beer, wine, and liquor in the state. Alcohol may be purchased between 7 a.m. and 2:30 a.m for consumption at the premise it was sold at, or between 6 a.m. and 2:30 a.m. if it is bought and taken off premise. In 2020, Oregon began allowing the sale of alcohol via home delivery services. As of 2007, consumption of spirits was on the rise while beer consumption held steady. That same year, 11% of beer sold in Oregon was brewed in-state, the highest figure in the United States.

The Prohibition era was the period from 1920 to 1933 when the United States prohibited the production, importation, transportation and sale of alcoholic beverages. The alcohol industry was curtailed by a succession of state legislatures, and finally ended nationwide under the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified on January 16, 1919. Prohibition ended with the ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment, which repealed the Eighteenth Amendment on December 5, 1933.

Alcohol laws are laws relating to manufacture, use, being under the influence of and sale of alcohol or alcoholic beverages. Common alcoholic beverages include beer, wine, (hard) cider, and distilled spirits. Definition of alcoholic beverage varies internationally, e.g., the United States defines an alcoholic beverage as "any beverage in liquid form which contains not less than one-half of one percent of alcohol by volume". Alcohol laws can restrict those who can produce alcohol, those who can buy it, when one can buy it, labelling and advertising, the types of alcoholic beverage that can be sold, where one can consume it, what activities are prohibited while intoxicated, and where one can buy it. In some cases, laws have even prohibited the use and sale of alcohol entirely.

Rum-running in Windsor, Ontario, Canada, was a major activity in the early part of the 20th century. In 1916, the State of Michigan, in the United States, banned the sale of alcohol, three years before prohibition became the national law in 1919. From that point forward, the City of Windsor, Ontario was a major site for alcohol smuggling and gang activity.

The Cullen–Harrison Act, named for its sponsors, Senator Pat Harrison and Representative Thomas H. Cullen, enacted by the United States Congress on March 21, 1933, and signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt the following day, legalized the sale in the United States of beer with an alcohol content of 3.2% and wine of similarly low alcohol content, thought to be too low to be intoxicating, effective April 7, 1933. Upon signing the legislation, Roosevelt made his famous remark, "I think this would be a good time for a beer."

A dry state was a state in the United States in which the manufacture, distribution, importation, and sale of alcoholic beverages was prohibited or tightly restricted. Some states, such as North Dakota, entered the United States as dry states, and others went dry after the passage of prohibition legislation or the Volstead Act. No state remains completely dry, but some states do contain dry counties.

Lambert v. Yellowley, 272 U.S. 581 (1926), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that reaffirmed the National Prohibition Act's limitation on the dispensation of alcoholic medicines. The five-to-four decision, written by Justice Louis D. Brandeis, affirmed the dismissal of a suit in which New York City physician Samuel Lambert sought to prevent Edward Yellowley, the acting federal prohibition director, from enforcing the Prohibition Act so as to preclude him from prescribing alcoholic medicines. The decision affirmed the police powers of the individual states, as well as the power of the Necessary and Proper Clause of the United States Constitution, which was cited in upholding the Prohibition Act's limitations as a necessary and proper implementation of the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Oklahoma Beer Act of 1933 is a United States public law legalizing the manufacture, possession, and sale of low-point beer in the State of Oklahoma. The Act of Congress cites the federal statute is binding with the cast of legal votes by the State of Oklahoma constituents or legislative action by the Oklahoma Legislature.

Medicinal Liquor Prescriptions Act of 1933 is a United States federal statute establishing prescription limitations for physicians possessing a permit to dispense medicinal liquor. The public law seek to abolish the use of the medicinal liquor prescription form introducing medicinal liquor revenue stamps as a substitution for official prescription blanks.

The Consequences of Prohibition did not just include effects on people's drinking habits but also on the worldwide economy, the people's trust of the government, and the public health system. Alcohol, from the rise of the temperance movement to modern day restrictions around the world, has long been a source of turmoil. When alcoholic beverages were first banned under the Volstead Act in 1919, the United States government had little idea of the severity of the consequences. It was first thought that a ban on alcohol would increase the moral character of society, but a ban on alcohol had vast unintended consequences.