Beauty is commonly described as a feature of objects that makes these objects pleasurable to perceive. Such objects include landscapes, sunsets, humans and works of art. Beauty, together with art and taste, is the main subject of aesthetics, one of the major branches of philosophy. As a positive aesthetic value, it is contrasted with ugliness as its negative counterpart. Along with truth and goodness it is one of the transcendentals, which are often considered the three fundamental concepts of human understanding.

The halo effect is the tendency for positive impressions of a person, company, brand or product in one area to positively influence one's opinion or feelings in other areas. Halo effect is “the name given to the phenomenon whereby evaluators tend to be influenced by their previous judgments of performance or personality.” The halo effect which is a cognitive bias can possibly prevent someone from accepting a person, a product or a brand based on the idea of an unfounded belief on what is good or bad.

Interpersonal attraction as a part of social psychology is the study of the attraction between people which leads to the development of platonic or romantic relationships. It is distinct from perceptions such as physical attractiveness, and involves views of what is and what is not considered beautiful or attractive.

Physical attractiveness is the degree to which a person's physical features are considered aesthetically pleasing or beautiful. The term often implies sexual attractiveness or desirability, but can also be distinct from either. There are many factors which influence one person's attraction to another, with physical aspects being one of them. Physical attraction itself includes universal perceptions common to all human cultures such as facial symmetry, sociocultural dependent attributes and personal preferences unique to a particular individual.

Cuteness is a subjective term describing a type of attractiveness commonly associated with youth and appearance, as well as a scientific concept and analytical model in ethology, first introduced by Konrad Lorenz. Lorenz proposed the concept of baby schema (Kindchenschema), a set of facial and body features that make a creature appear "cute" and activate ("release") in others the motivation to care for it. Cuteness may be ascribed to people as well as things that are regarded as attractive or charming.

Facial symmetry is one specific measure of bodily symmetry. Along with traits such as averageness and youthfulness it influences judgments of aesthetic traits of physical attractiveness and beauty. For instance, in mate selection, people have been shown to have a preference for symmetry.

A psychological adaptation is a functional, cognitive or behavioral trait that benefits an organism in its environment. Psychological adaptations fall under the scope of evolved psychological mechanisms (EPMs), however, EPMs refer to a less restricted set. Psychological adaptations include only the functional traits that increase the fitness of an organism, while EPMs refer to any psychological mechanism that developed through the processes of evolution. These additional EPMs are the by-product traits of a species’ evolutionary development, as well as the vestigial traits that no longer benefit the species’ fitness. It can be difficult to tell whether a trait is vestigial or not, so some literature is more lenient and refers to vestigial traits as adaptations, even though they may no longer have adaptive functionality. For example, xenophobic attitudes and behaviors, some have claimed, appear to have certain EPM influences relating to disease aversion, however, in many environments these behaviors will have a detrimental effect on a person's fitness. The principles of psychological adaptation rely on Darwin's theory of evolution and are important to the fields of evolutionary psychology, biology, and cognitive science.

The fusiform face area is a part of the human visual system that is specialized for facial recognition. It is located in the inferior temporal cortex (IT), in the fusiform gyrus.

The psychology of art is the scientific study of cognitive and emotional processes precipitated by the sensory perception of aesthetic artefacts, such as viewing a painting or touching a sculpture. It is an emerging multidisciplinary field of inquiry, closely related to the psychology of aesthetics, including neuroaesthetics.

Koinophilia is an evolutionary hypothesis proposing that during sexual selection, animals preferentially seek mates with a minimum of unusual or mutant features, including functionality, appearance and behavior. Koinophilia intends to explain the clustering of sexual organisms into species and other issues described by Darwin's Dilemma. The term derives from the Greek, koinos, "common", "that which is shared", and philia, "fondness".

Sexual selection in humans concerns the concept of sexual selection, introduced by Charles Darwin as an element of his theory of natural selection, as it affects humans. Sexual selection is a biological way one sex chooses a mate for the best reproductive success. Most compete with others of the same sex for the best mate to contribute their genome for future generations. This has shaped human evolution for many years, but reasons why humans choose their mates are not fully understood. Sexual selection is quite different in non-human animals than humans as they feel more of the evolutionary pressures to reproduce and can easily reject a mate. The role of sexual selection in human evolution has not been firmly established although neoteny has been cited as being caused by human sexual selection. It has been suggested that sexual selection played a part in the evolution of the anatomically modern human brain, i.e. the structures responsible for social intelligence underwent positive selection as a sexual ornamentation to be used in courtship rather than for survival itself, and that it has developed in ways outlined by Ronald Fisher in the Fisherian runaway model. Fisher also stated that the development of sexual selection was "more favourable" in humans.

The Kewpie doll effect is a term used in developmental psychology derived from research in ethology to help explain how a child's physical features, such as lengthened forehead and rounded face, motivate the infant's caregiver to take care of them. The child's physical features are said to resemble a Kewpie doll.

The processing fluency theory of aesthetic pleasure is a theory in psychological aesthetics on how people experience beauty. Processing fluency is the ease with which information is processed in the human mind.

Mate preferences in humans refers to why one human chooses or chooses not to mate with another human and their reasoning why. Men and women have been observed having different criteria as what makes a good or ideal mate. A potential mate's socioeconomic status has also been seen as having a noticeable effect, especially in developing areas where social status is more emphasized.

Developmental homeostasis is a process in which animals develop more or less normally, despite defective genes and deficient environments. It is an organisms ability to overcome certain circumstances in order to develop normally. This can be either a physical or mental circumstance that interferes with either a physical or mental trait. Many species have a specific norm, where those who fit that norm prosper while those who don't are killed or find it difficult to thrive. It is important that the animal be able to interact with the other group members effectively. Animals must learn their species' norms early to live a normal, successful life for that species.

Lookism is a term that describes the discriminatory treatment of people who are considered physically unattractive. It occurs in a variety of settings, including dating, social environments, and workplaces. Lookism has received less cultural attention than other forms of discrimination and typically does not have the legal protections that other forms often have, but it is still widespread and significantly affects people's opportunities in terms of romantic relationships, job opportunities, and other realms of life.

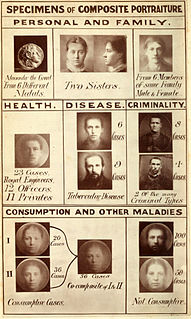

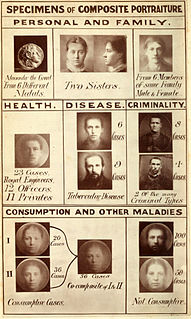

Composite portraiture is a technique invented by Sir Francis Galton in the 1880s after a suggestion by Herbert Spencer for registering photographs of human faces on the two eyes to create an "average" photograph of all those in the photographed group.

Mate value is derived from Charles Darwin's theory of evolution and sexual selection, as well as the social exchange theory of relationships. Mate value is defined as the sum of traits that are perceived as desirable, representing genetic quality and/or fitness (biology), an indication of a potential mate's reproductive success. Based on mate desirability and mate preference, mate value underpins mate selection and the formation of romantic relationships.

Female intrasexual competition is competition between women over a potential mate. Such competition might include self-promotion, derogation of other women, and direct and indirect aggression toward other women. Factors that influence female intrasexual competition include the genetic quality of available mates, hormone levels, and interpersonal dynamics.

The ovulatory shift hypothesis holds that women experience evolutionarily adaptive changes in subconscious thoughts and behaviors related to mating during different parts of the ovulatory cycle. It suggests that what women want, in terms of men, changes throughout the menstrual cycle. Two meta-analyses published in 2014 reached opposing conclusions on whether the existing evidence was robust enough to support the prediction that women's mate preferences change across the cycle. A newer 2018 review does not show women changing the type of men they desire at different times in their fertility cycle.