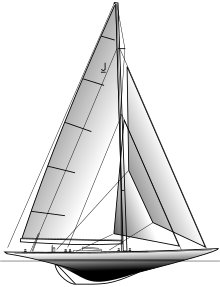

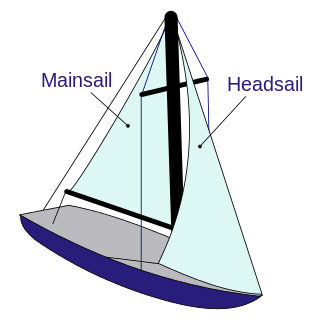

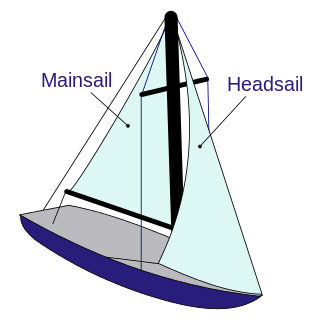

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sails fore and aft, or as a gaff-rig with triangular foresail(s) and a gaff rigged mainsail.

A schooner is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schooner also has a square topsail on the foremast, to which may be added a topgallant. Differing definitions leave uncertain whether the addition of a fore course would make such a vessel a brigantine. Many schooners are gaff-rigged, but other examples include Bermuda rig and the staysail schooner.

A sailboat or sailing boat is a boat propelled partly or entirely by sails and is smaller than a sailing ship. Distinctions in what constitutes a sailing boat and ship vary by region and maritime culture.

A sailing vessel's rig is its arrangement of masts, sails and rigging. Examples include a schooner rig, cutter rig, junk rig, etc. A rig may be broadly categorized as "fore-and-aft", "square", or a combination of both. Within the fore-and-aft category there is a variety of triangular and quadrilateral sail shapes. Spars or battens may be used to help shape a given kind of sail. Each rig may be described with a sail plan—formally, a drawing of a vessel, viewed from the side.

A jib is a triangular sail that sets ahead of the foremast of a sailing vessel. Its tack is fixed to the bowsprit, to the bows, or to the deck between the bowsprit and the foremost mast. Jibs and spinnakers are the two main types of headsails on a modern boat.

The Bermuda sloop is a historical type of fore-and-aft rigged single-masted sailing vessel developed on the islands of Bermuda in the 17th century. Such vessels originally had gaff rigs with quadrilateral sails, but evolved to use the Bermuda rig with triangular sails. Although the Bermuda sloop is often described as a development of the narrower-beamed Jamaica sloop, which dates from the 1670s, the high, raked masts and triangular sails of the Bermuda rig are rooted in a tradition of Bermudian boat design dating from the earliest decades of the 17th century. It is distinguished from other vessels with the triangular Bermuda rig, which may have multiple masts or may not have evolved in hull form from the traditional designs.

A jibe (US) or gybe (Britain) is a sailing maneuver whereby a sailing vessel reaching downwind turns its stern through the wind, which then exerts its force from the opposite side of the vessel. Because the mainsail boom can swing across the cockpit quickly, jibes are potentially dangerous to person and rigging compared to tacking. Therefore, accidental jibes are to be avoided while the proper technique must be applied so as to control the maneuver. For square-rigged ships, this maneuver is called wearing ship.

A spinnaker is a sail designed specifically for sailing off the wind on courses between a reach to downwind. Spinnakers are constructed of lightweight fabric, usually nylon, and are often brightly colored. They may be designed to perform best as either a reaching or a running spinnaker, by the shaping of the panels and seams. They are attached at only three points and said to be flown.

A mainsail is a sail rigged on the main mast of a sailing vessel.

A cutter is a name for various types of watercraft. It can apply to the rig of a sailing vessel, to a governmental enforcement agency vessel, to a type of ship's boat which can be used under sail or oars, or, historically, to a type of fast-sailing vessel introduced in the 18th century, some of which were used as small warships.

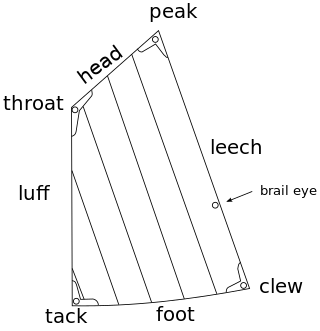

Gaff rig is a sailing rig in which the sail is four-cornered, fore-and-aft rigged, controlled at its peak and, usually, its entire head by a spar (pole) called the gaff. Because of the size and shape of the sail, a gaff rig will have running backstays rather than permanent backstays.

Running rigging is the rigging of a sailing vessel that is used for raising, lowering, shaping and controlling the sails on a sailing vessel—as opposed to the standing rigging, which supports the mast and bowsprit. Running rigging varies between vessels that are rigged fore and aft and those that are square-rigged.

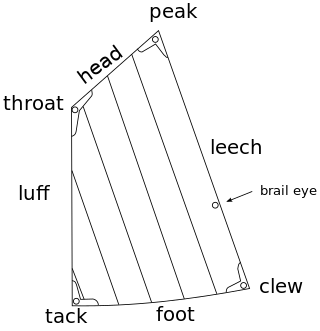

Sail components include the features that define a sail's shape and function, plus its constituent parts from which it is manufactured. A sail may be classified in a variety of ways, including by its orientation to the vessel and its shape,. Sails are typically constructed out of flexible material that is shaped by various means, while in use, to offer an appropriate airfoil, according to the strength and apparent direction of the wind. A variety of features and fittings allow the sail to be attached to lines and spars.

The spritsail is a four-sided, fore-and-aft sail that is supported at its highest points by the mast and a diagonally running spar known as the sprit. The foot of the sail can be stretched by a boom or held loose-footed just by its sheets. A spritsail has four corners: the throat, peak, clew, and tack. The Spritsail can also be used to describe a rig that uses a spritsail.

A fractional rig on a sailing vessel consists of a foresail, such as a jib or genoa sail, that does not reach all the way to the top of the mast.

The junk rig, also known as the Chinese lugsail, Chinese balanced lug sail, or sampan rig, is a type of sail rig in which rigid members, called battens, span the full width of the sail and extend the sail forward of the mast.

The Bermuda Fitted Dinghy is a type of racing-dedicated sail boat used for competitions between the yacht clubs of Bermuda. Although the class has only existed for about 130 years, the boats are a continuance of a tradition of boat and ship design in Bermuda that stretches back to the earliest decades of the 17th century.

A sail is a tensile structure, which is made from fabric or other membrane materials, that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails may be made from a combination of woven materials—including canvas or polyester cloth, laminated membranes or bonded filaments, usually in a three- or four-sided shape.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to sailing:

A sail plan is a drawing of a sailing craft, viewed from the side, depicting its sails, the spars that carry them and some of the rigging that supports the rig. By extension, "sail plan" describes the arrangement of sails on a craft. A sailing craft may be waterborne, an iceboat, or a sail-powered land vehicle.