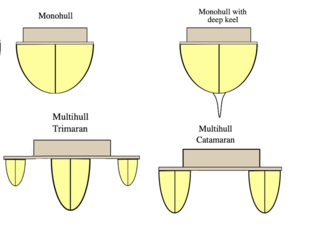

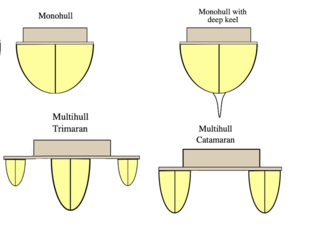

A multihull is a boat or ship with more than one hull, whereas a vessel with a single hull is a monohull. The most common multihulls are catamarans, and trimarans. There are other types, with four or more hulls, but such examples are very rare and tend to be specialised for particular functions.

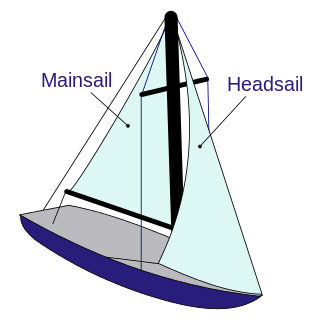

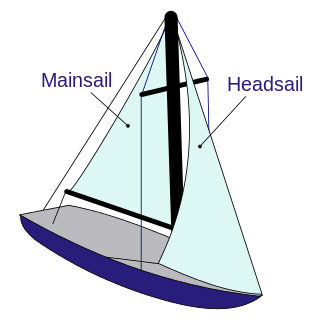

A sailboat or sailing boat is a boat propelled partly or entirely by sails and is smaller than a sailing ship. Distinctions in what constitutes a sailing boat and ship vary by region and maritime culture.

A catamaran is a watercraft with two parallel hulls of equal size. The distance between a catamaran's hulls imparts resistance to rolling and overturning. Catamarans typically have less hull volume, smaller displacement, and shallower draft (draught) than monohulls of comparable length. The two hulls combined also often have a smaller hydrodynamic resistance than comparable monohulls, requiring less propulsive power from either sails or motors. The catamaran's wider stance on the water can reduce both heeling and wave-induced motion, as compared with a monohull, and can give reduced wakes.

An outrigger is a projecting structure on a boat, with specific meaning depending on types of vessel. Outriggers may also refer to legs on a wheeled vehicle that are folded out when it needs stabilization, for example on a crane that lifts heavy loads.

Outrigger boats are various watercraft featuring one or more lateral support floats known as outriggers, which are fastened to one or both sides of the main hull. They can range from small dugout canoes to large plank-built vessels. Outrigger boats can also vary in their configuration, from the ancestral double-hull configuration (catamarans), to single-outrigger vessels prevalent in the Pacific Islands and Madagascar, to the double-outrigger vessels (trimarans) prevalent in Island Southeast Asia. They are traditionally fitted with Austronesian sails, like the crab claw sails and tanja sails, but in modern times are often fitted with petrol engines.

Proas are various types of multi-hull outrigger sailboats of the Austronesian peoples. The terms were used for native Austronesian ships in European records during the Colonial era indiscriminately, and thus can confusingly refer to the double-ended single-outrigger boats of Oceania, the double-outrigger boats of Island Southeast Asia, and sometimes ships with no outriggers or sails at all.

The term beachcat is an informal name for one of the most common types of small recreational sailboats, minimalist 14 to 20 foot catamarans, almost always with a cloth "trampoline" stretched between the two hulls, typically made of fiberglass or more recently rotomolded plastic. The name comes from the fact that they are designed to be sailed directly off a sand beach, unlike most other small boats which are launched from a ramp. The average 8 foot width of the beachcat means it can also sit upright on the sand and is quite stable in this position, unlike a monohull of the same size. The Hobie 14 and Hobie 16 are two of the earliest boats of this type that achieved widespread popularity, and popularized the term as well as created the template for this type of boat.

The vinta is a traditional outrigger boat from the Philippine island of Mindanao. The boats are made by Sama-Bajau, Tausug and Yakan peoples living in the Sulu Archipelago, Zamboanga peninsula, and southern Mindanao. Vinta are characterized by their colorful rectangular lug sails (bukay) and bifurcated prows and sterns, which resemble the gaping mouth of a crocodile. Vinta are used as fishing vessels, cargo ships, and houseboats. Smaller undecorated versions of the vinta used for fishing are known as tondaan.

The Astus 14.1 is a 14 ft (4.18m) trimaran dinghy aimed at recreational sailing and racing. The trimaran design is unusual for a boat of this size but is said to combine the features of other types of design: pointing ability of a monohull dinghy, reaching ability of a catamaran, and planing ability of a skiff. The stability provided by the floats makes the boat accessible to beginners and single-handed racers.

Austal Limited is an Australian-based global ship building company and defence prime contractor that specialises in the design, construction and support of defence and commercial vessels. Austal's product range includes naval vessels, high-speed ferries, and supply or crew transfer vessels for offshore windfarms and oil and gas platforms.

Telstar trimarans is a line of trimarans most recently built by the Performance Cruising Inc shipyard in Annapolis, Maryland.

VPLP design is a French-based naval architectural firm founded by Marc Van Peteghem and Vincent Lauriot-Prévost, responsible for designing some of the world's most innovative racing boats. Their designs presently hold many of the World Speed Sailing records.

James Wharram was a British multihull pioneer and designer of catamarans.

Camakau are a traditional watercraft of Fiji. Part of the broader Austronesian tradition, they are similar to catamarans, outrigger canoes, or smaller versions of the drua, but are larger than a takia. These vessels were built primarily for the purposes of travelling between islands and for trade. These canoes are single hulled, with an outrigger and a cama, a float, with both ends of the hull being symmetrical. They were very large, capable of travelling open ocean, and have been recorded as being up to 70 ft in length.

The Ocean Bird is a class of trimaran sailboat designed by John Westell and produced by Honnor Marine Ltd. at Totnes, Teignmouth in the 1970s, featuring fold-in lateral floats on a webless steel-beam frame chosen to provide stability against heeling, yet allow a compact footprint in harbour.

Bangka are various native watercraft of the Philippines. It originally referred to small double-outrigger dugout canoes used in rivers and shallow coastal waters, but since the 18th century, it has expanded to include larger lashed-lug ships, with or without outriggers. Though the term used is the same throughout the Philippines, "bangka" can refer to a very diverse range of boats specific to different regions. Bangka was also spelled as banca, panca, or panga in Spanish. It is also known archaically as sakayan.

The F-31 Sport Cruiser is a family of American trailerable trimaran sailboats that was designed by New Zealander Ian Farrier and first built in 1991.

Polynesian multihull terminology, such as "ama", "aka" and "vaka" are multihull terms that have been widely adopted beyond the South Pacific where these terms originated. This Polynesian terminology is in common use in the Americas and the Pacific but is almost unknown in Europe, where the English terms "hull" and "outrigger" form normal parlance. Outriggers, catamarans, and outrigger boats are a common heritage of all Austronesian peoples and predate the Micronesian and Polynesian expansion into the Pacific. They are also the dominant forms of traditional ships in Island Southeast Asian and Malagasy Austronesian cultures, where local terms are used.

Sakman, better known in western sources as flying proas, are traditional sailing outrigger boats of the Chamorro people of the Northern Marianas. They are characterized by a single outrigger and a crab claw sail. They are the largest native sailing ships (ladjak) of the Chamorro people. Followed by the slightly smaller lelek and the medium-sized duding. They are similar to other traditional sailing ships of Micronesia, like the wa, baurua, and the walap. These ships were once used for trade and transportation between islands.

Austronesian vessels are the traditional seafaring vessels of the Austronesian peoples of Taiwan, Maritime Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar. They also include indigenous ethnic minorities in Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, Hainan, the Comoros, and the Torres Strait Islands.