Feeding

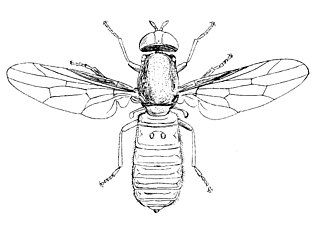

Food habits of most species are largely unknown but broad statements may be made. Diptera are important pollinators and plant pests.

Detritivores

Many Diptera are detritivores. Typical are Dryomyza anilis and, notably, Musca domestica .

Flower feeders

Many adult Brachycera feed on flowers notably hover fly which obtain all their protein requirements by feeding on pollen. The Calyptratae exhibit flower feeding in all families except Hippoboscidae Nycterebidae and Glossinidae and in the Acalyptratae the Conopidae are well known flower feeders. Other flower feeding Brachycerous families are Empididae, Stratiomyidae (soldier flies) and the Acroceridae like various members of the Nemestrinidae (tangle-veined flies), Bombyliidae (bee flies) and Tabanidae (horse-fly) are nectar feeders with exceptionally long proboscises, sometimes longer than the entire bodily length of the insect. Flower feeding Nematocera include Bibionidae (March flies) and some species in Tipulidae (Crane flies) and other families. [5] [6]

- Syrphidae

- Bombylius- note the proboscis

- Tachinidae

- Tipiludae (Nematocera)

Predators

Adult Asilidae, Empididae and Scathophagidae feed on other insects, including smaller Diptera, Dolichopodidae and some Ephydridae feed on a variety of animal prey.

- Tachypeza nubila: Empididae with prey

- Dysmachus fuscipennis: Asilidae with beetle prey

- Cordilura: Scathophagidae hunting

- Ochthera an Ephydridae with raptorial forelegs

Both male and female mosquitoes feed on nectar and plant juices, but in many species the mouthparts of the females are adapted for piercing the skin of animal hosts and feed on blood as ectoparasites. The most important function of blood meals is to obtain proteins as materials for egg production. For females to risk their lives on blood sucking while males abstain, is not a strategy limited to the mosquitoes; it also occurs in some other families, such as the Tabanidae. Most female horse flies feed on mammal blood, but some species are known to feed on birds, amphibians or reptiles. Other bloodfeeding Diptera are Ceratopogonidae Phlebotominae Hippoboscidae, Hydrotaea and Philornis downsi (Muscidae), Spaniopsis and Symphoromyia Rhagionidae. There are no known acalyptrates that are obligate blood-feeders.

- Haemotopota pluvialis feeding

- Phlebotomus pappatasi after a blood meal

- Sheep ked, Melophagus ovinus, a highly specialised blood-feeding dipteran ectoparasite

Larvae

The larvae of Diptera feed on a diverse array of nutrients ; often these are different from those of adults, for instance the larvae of Syrphidae in which family the adults are flower-feeding are saprotrophs, eating decaying plant or animal matter, or insectivores, eating aphids, thrips, and other plant-sucking insects.

Larval Diptera feed in leaf-litter, in leaves, stems, roots, flower and seed heads of plants, moss, fungi, rotting wood, rotting fruit or other organic matter such as slime, flowing sap, and rotting cacti, carrion, dung, detritus in mammal bird or wasp nests, fine organic material including insect frass and micro-organisms. Many Diptera larvae are predatory, sometimes on the larvae of other Diptera.

Many Agromyzidae are leaf miners. Some Tephritidae are leaf miners or gall formers. The larvae of all Oestridae oestrids are obligate parasites of mammals. (Oestridae include the highest proportion of species whose larvae live as obligate parasites within the bodies of mammals. Most other species prone to cause myiasis are members of related families, such as the Calliphoridae. There are roughly 150 known species worldwide.) Tachinidae larvae are parasitic on other insects. Conopidae larvae are endoparasites of bees and wasps or of cockroaches and calyptrate Diptera, Pyrgotidae larvae are endoparasites of adult scarab beetles. Sciomyzidae larvae are exclusively associated with freshwater and terrestrial snails, or slugs. They feed on snails as predators, parasitoids, or scavengers. Females search out snails for oviposition. Known Odiniidae larvae live in the tunnels of wood-boring larvae of Coleoptera, Lepidoptera, and other Diptera and function as scavengers or predators of the host larvae. Oedoparena larvae feed on barnacles. The larvae of Acroceridae and some Bombyliidae are hypermetamorphic.

- : Phytomyza angelicastri: Agromyzidae leaf mine

- A young mule heavily infestated with Gasterophilus haemorrhoidalis larvae

- Delia radicum Athomyiidae larvae feeding on cauliflower

- Damage by gall midges (Cecidomyiidae) on pear leaves

Milichiidae especially Pholeomyia and Milichiella Milichiidae are kleptoparasites of predatory invertebrates, and accordingly are commonly known as freeloader flies or jackal flies.