Birch bark tar (sometimes referred to as birch bark pitch) is a substance that is synthesized by dry distillation of birch tree bark.

Birch bark tar (sometimes referred to as birch bark pitch) is a substance that is synthesized by dry distillation of birch tree bark.

Birch bark tar is mainly composed of triterpenoid compounds of the lupane and oleanane family, which can be used as biomarkers to identify birch bark tar in the archaeological record. The most characteristic molecules are betulin and lupeol, which are also present in birch bark. [1] [2] Some of these molecules degrade into other lupane and oleanane skeleton triperpenes. The most commonly found additional molecules are lupenone, betulone, lupa-2,20(29)-dien-28-ol, lupa-2,20(29)-diene and allobetulin. [3] [4] [5]

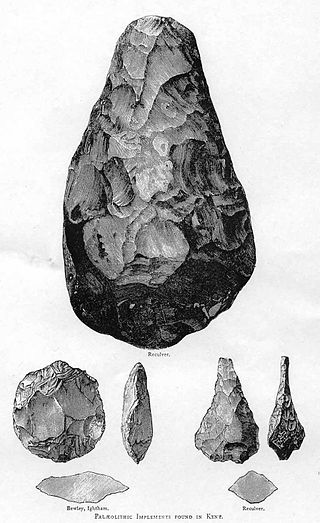

Birch bark tar use as an adhesive began in the Middle Paleolithic. Neanderthals produced tar through dry distillation of birch bark as early as 200,000 years ago. [6] A 2019 study demonstrated that birch bark tar production can be a simpler, more discoverable process by directly burning birch bark under overhanging stone surfaces in open-air conditions. [7] However, at Königsaue (Germany), Neanderthals did not make tar with this method but rather employed a technically more demanding underground production method. [8] A find from the Dutch North Sea [9] and two tools from the Italian site Campitello show that Neanderthals used birch bark tar as a backing on small 'domestic' stone tools.

Birch bark tar also has been used as a disinfectant, in leather dressing, and in medicine.[ citation needed ]

A piece of 5,000-year-old chewing gum made from birch bark tar, and still bearing tooth imprints, was found in Kierikki, Finland. [10] Genetic material left in the gum enabled novel research to identify population movements, types of food consumed, and types of oral bacteria found on their teeth. [11]

A different chewing gum sample, dated to 5,700 years old, was found in southern Denmark. A complete human genome and oral microbiome was sequenced from chewed birch bark tar. Researchers identified that the individual who chewed the gum was a female who was closely related genetically to hunter-gatherers from mainland Europe. [12]

Fletching on arrows were fastened with birch bark tar, and rawhide lashing and birch bark tar were used to fix axe blades in the Mesolithic period.

Birch bark tar was more frequently discovered in archaeological contexts dating from the Neolithic to the Iron Age. For example, birch bark tar was identified to serve as an adhesive to repair [13] [14] [15] [16] and decorate/paint ceramic vessels, [17] as a sealing/waterproofing agent. [18] [19] A well-known example of birch bark tar hafting during the copper age is Ötzi’s hafted arrow points and copper axe. [20] Multiple discoveries show that birch bark tar was also used to assemble metal artefacts, such as pendants and other ornaments, on both a functional and decorative level. [21] [22] During the Roman Era, birch bark tar is mostly replaced by wood tar, [23] [24] but birch bark tar is still used, for example, to decorate hinges and other bone objects. [25]

Russia leather is a water-resistant leather, oiled with birch bark oil after tanning. This leather was a major export good from seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Russia, as the availability of birch bark oil limited its geographical production. [26] The oil impregnation also deterred insect attack and gave a distinctive and pleasant aroma that was seen as a mark of quality in leather.

Birch bark tar is also one of the components of Vishnevsky liniment. [27]

Birch bark tar oil is an effective repellent of gastropods. [28] The repellent effect lasts about two weeks. [28] The repellent effect of birch bark tar oil mixed with petroleum jelly and applied to a fence can last up to several months. [28]

Birch bark tar oil has strong antiseptic properties, [29] owing to a large amount of phenol derivatives and terpenoid derivatives.

Birch bark tar oil was used in the eighteenth century alongside civet and castoreum and many other aromatic substances to scent the fine Spanish leather Peau d'Espagne. At the turn of the twentieth century, birch bark tar had become a specialty fragrance material in perfumery as a base note to impart a leathery, smoky note in fragrances, especially from the leather and tobacco genre, and to a lesser extent in Chypres, especially Cuir de Russie perfumes and fragrance bases, typically together with castoreum and isobutyl quinoline. It is used as an ingredient in some soaps, i.e. the scent of Imperial Leather soap, though other tars (i.e. from pine, coal) with an equally phenolic and smoky odour are more commonly used in soaps as a medicating agent.

Adhesive, also known as glue, cement, mucilage, or paste, is any non-metallic substance applied to one or both surfaces of two separate items that binds them together and resists their separation.

The Mesolithic or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymously, especially for outside northern Europe, and for the corresponding period in the Levant and Caucasus. The Mesolithic has different time spans in different parts of Eurasia. It refers to the final period of hunter-gatherer cultures in Europe and the Middle East, between the end of the Last Glacial Maximum and the Neolithic Revolution. In Europe it spans roughly 15,000 to 5,000 BP; in the Middle East roughly 20,000 to 10,000 BP. The term is less used of areas farther east, and not at all beyond Eurasia and North Africa.

Tannins are a class of astringent, polyphenolic biomolecules that bind to and precipitate proteins and various other organic compounds including amino acids and alkaloids.

Chewing gum is a soft, cohesive substance designed to be chewed without being swallowed. Modern chewing gum is composed of gum base, sweeteners, softeners/plasticizers, flavors, colors, and, typically, a hard or powdered polyol coating. Its texture is reminiscent of rubber because of the physical-chemical properties of its polymer, plasticizer, and resin components, which contribute to its elastic-plastic, sticky, chewy characteristics.

Electron ionization is an ionization method in which energetic electrons interact with solid or gas phase atoms or molecules to produce ions. EI was one of the first ionization techniques developed for mass spectrometry. However, this method is still a popular ionization technique. This technique is considered a hard ionization method, since it uses highly energetic electrons to produce ions. This leads to extensive fragmentation, which can be helpful for structure determination of unknown compounds. EI is the most useful for organic compounds which have a molecular weight below 600. Also, several other thermally stable and volatile compounds in solid, liquid and gas states can be detected with the use of this technique when coupled with various separation methods.

Cinnamaldehyde is an organic compound with the formula or C₆H₅CH=CHCHO. Occurring naturally as predominantly the trans (E) isomer, it gives cinnamon its flavor and odor. It is a phenylpropanoid that is naturally synthesized by the shikimate pathway. This pale yellow, viscous liquid occurs in the bark of cinnamon trees and other species of the genus Cinnamomum. The essential oil of cinnamon bark is about 90% cinnamaldehyde. Cinnamaldehyde decomposes to styrene because of oxidation as a result of bad storage or transport conditions. Styrene especially forms in high humidity and high temperatures. This is the reason why cinnamon contains small amounts of styrene.

A toothpick is a small thin stick of wood, plastic, bamboo, metal, bone or other substance with at least one and sometimes two pointed ends to insert between teeth to remove detritus, usually after a meal. Toothpicks are also used for festive occasions to hold or spear small appetizers or as a cocktail stick, and can be decorated with plastic frills or small paper umbrellas or flags.

Chewing or mastication is the process by which food is crushed and ground by the teeth. It is the first step in the process of digestion, allowing a greater surface area for digestive enzymes to break down the foods.

Wintergreen is a group of aromatic plants. The term wintergreen once commonly referred to plants that remain green throughout the winter. The term evergreen is now more commonly used for this characteristic.

An insect repellent is a substance applied to the skin, clothing, or other surfaces to discourage insects from landing or climbing on that surface. Insect repellents help prevent and control the outbreak of insect-borne diseases such as malaria, Lyme disease, dengue fever, bubonic plague, river blindness, and West Nile fever. Pest animals commonly serving as vectors for disease include insects such as flea, fly, and mosquito; and ticks (arachnids).

Birch bark or birchbark is the bark of several Eurasian and North American birch trees of the genus Betula.

Eucalyptol is a monoterpenoid colorless liquid, and a bicyclic ether. It has a fresh camphor-like odor and a spicy, cooling taste. It is insoluble in water, but miscible with organic solvents. Eucalyptol makes up about 70–90% of eucalyptus oil. Eucalyptol forms crystalline adducts with hydrohalic acids, o-cresol, resorcinol, and phosphoric acid. Formation of these adducts is useful for purification.

Spruce gum is a chewing material made from the resin of spruce trees. In North America, spruce resin was chewed by Native Americans and was later introduced to the early American pioneers and was sold commercially by the 19th century, by John B. Curtis among others. It has also been used as an adhesive. Indigenous women in North America used spruce gum to caulk seams of birch-bark canoes.

The oldest undisputed examples of figurative art are known from Europe and from Sulawesi, Indonesia, dated about 35,000 years old . Together with religion and other cultural universals of contemporary human societies, the emergence of figurative art is a necessary attribute of full behavioral modernity.

Sibudu Cave is a rock shelter in a sandstone cliff in northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. It is an important Middle Stone Age site occupied, with some gaps, from 77000 years ago to 38000 years ago.

The Wezmeh Cave is an archaeological site near Islamabad Gharb, western Iran, around 470 km (290 mi) southwest of the capital Tehran. The site was discovered in 1999 and excavated in 2001 by a team of Iranian archaeologists under the leadership of Dr. Kamyar Abdi. Wezmeh cave was re-excavated by a team under direction of Fereidoun Biglari in 2019.

Neanderthals are an extinct group of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. The type specimen, Neanderthal 1, was found in 1856 in the Neander Valley in present-day Germany.

Almost everything about Neanderthal behaviour remains controversial. From their physiology, Neanderthals are presumed to have been omnivores, but animal protein formed the majority of their dietary protein, showing them to have been carnivorous apex predators and not scavengers. Although very little is known of their social organization, it appears patrilines would make up the nucleus of the tribe, and women would seek out partners in neighbouring tribes once reaching adolescence, presumably to avoid inbreeding. An analysis based on finger-length ratios suggests that Neanderthals were more sexually competitive and promiscuous than modern-day humans.

Russia leather is a particular form of bark-tanned cow leather. It is distinguished from other types of leather by a processing step that takes place after tanning, where birch oil is worked into the rear face of the leather. This produces a leather that is hard-wearing, flexible and resistant to water. The oil impregnation also deters insect damage. This leather was a major export good from Russia in the 17th and 18th centuries because of its high quality, its usefulness for a range of purposes, and the difficulty of replicating its manufacture elsewhere. It was an important item of trade for the Muscovy Company. In German-speaking countries, this leather was also known by the name Juchten or Juften.

In archaeology, Organic Residue Analysis (ORA) refers to the study of micro-remains trapped in or adhered to artifacts from the past. These organic residues can include lipids, proteins, starches, and sugars. By analyzing these residues, ORA can reveal insights into ancient dietary behaviors, agricultural practices, housing organization, technological advancements, and trade interactions. Furthermore, it provides information on the use of cosmetics, arts, crafts, medicine, and burial preparations in ancient societies.