Nutmeg is the seed, or the ground spice derived from that seed, of several tree species of the genus Myristica; fragrant nutmeg or true nutmeg is a dark-leaved evergreen tree cultivated for two spices derived from its fruit: nutmeg, from its seed, and mace, from the seed covering. It is also a commercial source of nutmeg essential oil and nutmeg butter. Indonesia is the main producer of nutmeg and mace, and the true nutmeg tree is native to its islands.

Cloves are the aromatic flower buds of a tree in the family Myrtaceae, Syzygium aromaticum. They are native to the Maluku Islands, or Moluccas, in Indonesia, and are commonly used as a spice, flavoring, or fragrance in consumer products, such as toothpaste, soaps, or cosmetics. Cloves are available throughout the year owing to different harvest seasons across various countries.

Black pepper is a flowering vine in the family Piperaceae, cultivated for its fruit, which is usually dried and used as a spice and seasoning. The fruit is a drupe (stonefruit) which is about 5 mm (0.20 in) in diameter, dark red, and contains a stone which encloses a single pepper seed. Peppercorns and the ground pepper derived from them may be described simply as pepper, or more precisely as black pepper, green pepper, or white pepper.

Mulled wine, also known as spiced wine, is an alcoholic drink usually made with red wine, along with various mulling spices and sometimes raisins, served hot or warm. It is a traditional drink during winter, especially around Christmas. It is usually served at Christmas markets in Europe, primarily in Germany, Czech Republic, Austria, Switzerland, Slovenia, Croatia, Hungary, Romania, Nordics, Baltics and eastern France. There are non-alcoholic versions of it. Vodka-spiked mulled wine can be found in Polish Christmas markets, where mulled wine is commonly used as a mixer.

Allspice, also known as Jamaica pepper, myrtle pepper, pimenta, or pimento, is the dried unripe berry of Pimenta dioica, a midcanopy tree native to the Greater Antilles, southern Mexico, and Central America, now cultivated in many warm parts of the world. The name allspice was coined as early as 1621 by the English, who valued it as a spice that combined the flavours of cinnamon, nutmeg, and clove.

Garam masala is a blend of ground spices originating from the Indian subcontinent. It is common in Indian, Pakistani, Nepalese, Bangladeshi, Sri Lankan and Caribbean cuisines. It is used alone or with other seasonings. The specific fixings differ by district, but it regularly incorporates a blend of flavors like cardamom, cinnamon, cumin, cloves and peppercorns. Garam masala can be found in a wide range of dishes, including marinades, pickles, stews, and curries.

Indian cuisine consists of a variety of regional and traditional cuisines native to the Indian subcontinent. Given the diversity in soil, climate, culture, ethnic groups, and occupations, these cuisines vary substantially and use locally available spices, herbs, vegetables, and fruits.

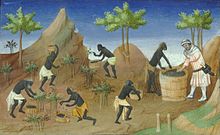

The spice trade involved historical civilizations in Asia, Northeast Africa and Europe. Spices such as cinnamon, cassia, cardamom, ginger, pepper, nutmeg, star anise, clove, and turmeric were known and used in antiquity and traded in the Eastern World. These spices found their way into the Near East before the beginning of the Christian era, with fantastic tales hiding their true sources.

Spice mixes are blended spices or herbs. When a certain combination of herbs or spices is called for in a recipe, it is convenient to blend these ingredients beforehand. Blends such as chili powder, curry powder, herbes de Provence, garlic salt, and other seasoned salts are traditionally sold pre-made by grocers, and sometimes baking blends such as pumpkin pie spice are also available. These spice mixes are also easily made by the home cook for later use.

Biryani is a mixed rice dish, mainly popular in South Asia. It is made with rice, some type of meat and spices. To cater to vegetarians, in some cases, it is prepared by substituting vegetables or paneer for the meat. Sometimes eggs and/or potatoes are also added.

Iraqi cuisine is a Middle Eastern cuisine that has its origins in the ancient Near East culture of the fertile crescent. Tablets found in ancient ruins in Iraq show recipes prepared in the temples during religious festivals—the first cookbooks in the world. Ancient Mesopotamia was home to a sophisticated and highly advanced civilization, in all fields of knowledge, including the culinary arts.

Chettinad cuisine is the cuisine of a community called the Nattukotai Chettiars, or Nagarathars, from the Chettinad region in Sivaganga district of Tamil Nadu state in India. Chettinad cuisine is perhaps the most renowned fare in the Tamil Nadu repertoire. It uses a variety of spices and the dishes are made with fresh ground masalas. Chettiars also use a variety of sun-dried meats and salted vegetables, reflecting the dry environment of the region. Most of the dishes are eaten with rice and rice based accompaniments such as dosas, appams, idiyappams, adais and idlis. The Chettiars, through their mercantile contacts with Burma, learnt to prepare a type of rice pudding made with sticky red rice. The chefs of manapatti village near Singampunari are experts in cooking Chettinad cuisine. They always used to cook in bulk orders for marriage functions, political functions, etc. though manapatti cooking is portrayed as madurai cuisine because it is located near to madurai district, it comes under chettinad cuisine only and it also comes under the chettinad region of sivagangai district. The entire village people is famous in the art of cooking.

Massaman curry is a rich, flavourful, and mildly spicy Thai curry. It is a fusion dish, combining ingredients from three sources: Persia, the Indian Subcontinent, and the Malay Archipelago with ingredients more commonly used in native Thai cuisine to make massaman curry paste. The substance of the dish is usually based on chicken or other meat, potatoes, onions, and peanuts. The richness comes from the coconut milk and cream used as a base, as for many Thai curries.

Qâlat daqqa, or Tunisian Five Spices, is a spice blend originating from Tunisia. It is made of cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, peppercorns, and grains of paradise mixed and ground, depending on its use, between a coarse grind and a fine powder. This spice blend is used to as both an aromatic and seasoning for meats and vegetable dishes. The flavor of the mixture is described as being "sweet and warm".

Mizrahi Jewish cuisine is an assortment of cooking traditions that developed among the Jews of the Middle East, North Africa, Asia, and Arab countries. Mizrahi Jews have also been known as Oriental Jews.

Curry paste is a mixture of ingredients in the consistency of a paste used in the preparation of a curry. There are different varieties of curry paste depending from the region and also within the same cuisine.

Grains of Selim are the seeds of a shrubby tree, Xylopia aethiopica, found in Africa. The seeds have a musky flavor and are used as a spice in a manner similar to black pepper, and as a flavouring agent that defines café Touba, the dominant style of coffee in Senegal. It is also known as Senegal pepper, Ethiopian pepper, and (historically) Moor pepper and Negro pepper. It also has many names in native languages of Africa, the most common of which is diarr in the Wolof language. It is called 'Etso' in the Ewe language of Ghana and Togo. It is sometimes referred to as African pepper or Guinea pepper, but these are ambiguous terms that may refer to Ashanti pepper and grains of paradise, among others.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to herbs and spices:

Bumbu is the Indonesian word for a blend of spices and for pastes and it commonly appears in the names of spice mixtures, sauces and seasoning pastes. The official Indonesian language dictionary describes bumbu as "various types of herbs and plants that have a pleasant aroma and flavour — such as ginger, turmeric, galangal, nutmeg and pepper — used to enhance the flavour of the food."