The Cushitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They are spoken primarily in the Horn of Africa, with minorities speaking Cushitic languages to the north in Egypt and Sudan, and to the south in Kenya and Tanzania. As of 2012, the Cushitic languages with over one million speakers were Oromo, Somali, Beja, Afar, Hadiyya, Kambaata, and Sidama.

Nubians are a Nilo-Saharan ethnic group indigenous to the region which is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt. They originate from the early inhabitants of the central Nile valley, believed to be one of the earliest cradles of civilization. In the southern valley of Egypt, Nubians differ culturally and ethnically from Egyptians, although they intermarried with members of other ethnic groups, especially Arabs. They speak Nubian languages as a mother tongue, part of the Northern Eastern Sudanic languages, and Arabic as a second language.

Medjay was a demonym used in various ways throughout ancient Egyptian history to refer initially to a nomadic group from Nubia and later as a generic term for desert-ranger police.

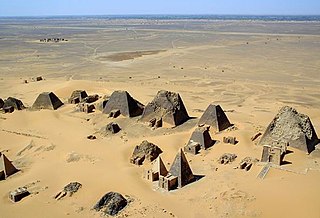

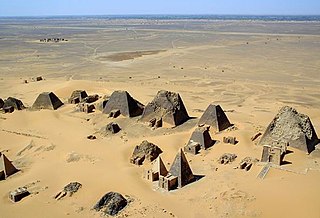

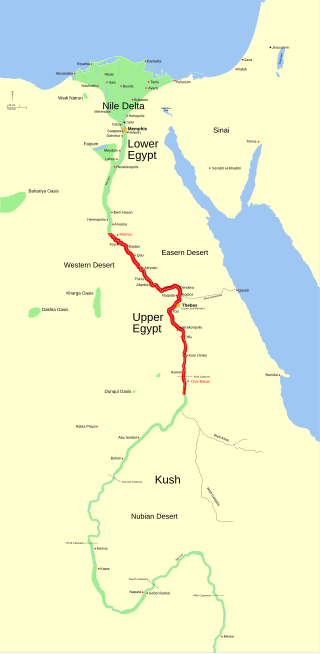

The Nubian pyramids were built by the rulers of the ancient Kushite kingdoms. The area of the Nile valley known as Nubia, which lies in northern present-day Sudan, was the site of three Kushite kingdoms during antiquity. The capital of the first was at Kerma. The second was centered on Napata. The third kingdom was centered on Meroë. The pyramids are built of granite and sandstone.

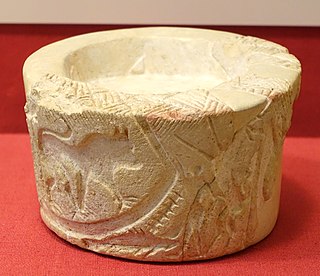

Kerma was the capital city of the Kerma culture, which was located in present-day Sudan at least 5,500 years ago. Kerma is one of the largest archaeological sites in ancient Nubia. It has produced decades of extensive excavations and research, including thousands of graves and tombs and the residential quarters of the main city surrounding the Western/Lower Deffufa.

Prehistoric Egypt and Predynastic Egypt is the period of time starting at the first human settlement and ending at the First Dynasty of Egypt around 3100 BC.

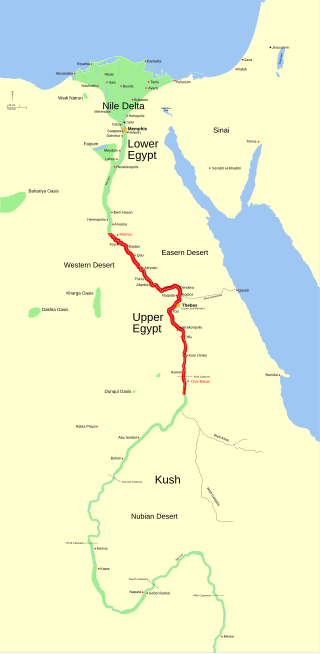

Lower Nubia is the northernmost part of Nubia, roughly contiguous with the modern Lake Nasser, which submerged the historical region in the 1960s with the construction of the Aswan High Dam. Many ancient Lower Nubian monuments, and all its modern population, were relocated as part of the International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia; Qasr Ibrim is the only major archaeological site which was neither relocated nor submerged. The intensive archaeological work conducted prior to the flooding means that the history of the area is much better known than that of Upper Nubia. According to David Wengrow, the A-Group Nubian polity of the late 4th millenninum BCE is poorly understood since most of the archaeological remains are submerged underneath Lake Nasser.

The Kingdom of Kerma or the Kerma culture was an early civilization centered in Kerma, Sudan. It flourished from around 2500 BC to 1500 BC in ancient Nubia. The Kerma culture was based in the southern part of Nubia, or "Upper Nubia", and later extended its reach northward into Lower Nubia and the border of Egypt. The polity seems to have been one of a number of Nile Valley states during the Middle Kingdom of Egypt. In the Kingdom of Kerma's latest phase, lasting from about 1700 to 1500 BC, it absorbed the Sudanese kingdom of Sai and became a sizable, populous empire rivaling Egypt. Around 1500 BC, it was absorbed into the New Kingdom of Egypt, but rebellions continued for centuries. By the eleventh century BC, the more-Egyptianized Kingdom of Kush emerged, possibly from Kerma, and regained the region's independence from Egypt.

The former Kingdom of Kerma in Nubia, was a province of ancient Egypt from the 16th century BCE to eleventh century BCE. During this period, the polity was ruled by a viceroy who reported directly to the Egyptian Pharaoh.

George Andrew Reisner Jr. was an American archaeologist of Ancient Egypt, Nubia and Palestine.

The A-Group culture was an ancient culture that flourished between the First and Second Cataracts of the Nile in Lower Nubia. It lasted from c. 3800 BC to c. 3100 BC.

The National Museum of Sudan or Sudan National Museum, abbreviated SNM, is a two-story building, constructed in 1955 and established as national museum in 1971.

The Naqada culture is an archaeological culture of Chalcolithic Predynastic Egypt, named for the town of Naqada, Qena Governorate. A 2013 Oxford University radiocarbon dating study of the Predynastic period suggests a beginning date sometime between 3,800 and 3,700 BC.

Nubian architecture is diverse and ancient. Permanent villages have been found in Nubia, which date from 6000 BC. These villages were roughly contemporary with the walled town of Jericho in Palestine.

Nubia is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the first cataract of the Nile and the confluence of the Blue and White Niles, or more strictly, Al Dabbah. It was the seat of one of the earliest civilizations of ancient Africa, the Kerma culture, which lasted from around 2500 BC until its conquest by the New Kingdom of Egypt under Pharaoh Thutmose I around 1500 BC, whose heirs ruled most of Nubia for the next 400 years. Nubia was home to several empires, most prominently the Kingdom of Kush, which conquered Egypt in the eighth century BC during the reign of Piye and ruled the country as its 25th Dynasty.

The Kingdom of Kush, also known as the Kushite Empire, or simply Kush, was an ancient kingdom in Nubia, centered along the Nile Valley in what is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt.

Egypt has a long and involved demographic history. This is partly due to the territory's geographical location at the crossroads of several major cultural areas: North Africa, the Middle East, the Mediterranean and Sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, Egypt has experienced several invasions and being part of many regional empires during its long history, including by the Canaanites, the Ancient Libyans, the Assyrians, the Kushites, the Persians, the Greeks, the Romans, and the Arabs.

El-Kurru was the first of the three royal cemeteries used by the Kushite royals of Napata, also referred to as Egypt's 25th Dynasty, and is home to some of the royal Nubian Pyramids. It is located between the 3rd and 4th cataracts of the Nile about 1 mile (1.6 km) west of the river in what is now Northern state, Sudan. El-Kurru was first excavated by George Reisner in 1918 and 1919 and after his death his assistant Dows Dunham took over his work and published the excavation report on El-Kurru in 1950. The El Kurru cemetery was primarily used from about 860 BC until 650 BC. The first tomb with a name attached to it is that of King Piye dating to about 750 BC, the sixteen earlier tombs possibly belong to Piye's royal predecessors. The last 25th dynasty king, Tantamani, was buried at El Kurru around 650 BC. The subsequent Napatan rulers chose to be buried at the royal cemetery at Nuri instead. However, in the mid-4th century the 20th king, whose name is unknown, chose to have his tomb, as well as that of his queen, built at El Kurru.

Qustul is an archaeological cemetery located on the eastern bank of the Nile in Lower Nubia, just opposite of Ballana near the Sudan frontier. The site has archaeological records from the A-Group culture, the New Kingdom of Egypt and the X-Group culture.

Kushite religion is the traditional belief system and pantheon of deities associated with the Ancient Nubians, who founded the Kingdom of Kush in the land of Nubia in present-day Sudan.