Related Research Articles

Jefferson Parish is a parish in the U.S. state of Louisiana. As of the 2020 census, the population was 440,781. Its parish seat is Gretna, its largest community is Metairie, and its largest incorporated city is Kenner. Jefferson Parish is included in the Greater New Orleans area.

The Louisiana State Penitentiary is a maximum-security prison farm in Louisiana operated by the Louisiana Department of Public Safety & Corrections. It is named "Angola" after the former slave plantation that occupied this territory. The plantation was named after the country of Angola from which many slaves originated before arriving in Louisiana.

Clarence Raymond Joseph Nagin Jr. is an American former politician who was the 60th Mayor of New Orleans, Louisiana, from 2002 to 2010. A Democrat, Nagin became internationally known in 2005 in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

Hurricane Katrina was a devastating and deadly Category 5 Atlantic hurricane that caused 1,836 fatalities and damages estimated between $97.4 billion to $145.5 billion in late August 2005, particularly in the city of New Orleans and its surrounding area. At the time, it was the costliest tropical cyclone on record, later tied by Hurricane Harvey in 2017. Katrina was the twelfth tropical cyclone, the fifth hurricane, and the third major hurricane of the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season. It was also the fourth-most intense Atlantic hurricane to make landfall in the contiguous United States, gauged by barometric pressure.

As the center of Hurricane Katrina passed southeast of New Orleans on August 29, 2005, winds downtown were in the Category 1 range with frequent intense gusts. The storm surge caused approximately 23 breaches in the drainage canal and navigational canal levees and flood walls. As mandated in the Flood Control Act of 1965, responsibility for the design and construction of the city’s levees belongs to the United States Army Corps of Engineers and responsibility for their maintenance belongs to the Orleans Levee Board. The failures of levees and flood walls during Katrina are considered by experts to be the worst engineering disaster in the history of the United States. By August 31, 2005, 80% of New Orleans was flooded, with some parts under 15 feet (4.6 m) of water. The famous French Quarter and Garden District escaped flooding because those areas are above sea level. The major breaches included the 17th Street Canal levee, the Industrial Canal levee, and the London Avenue Canal flood wall. These breaches caused the majority of the flooding, according to a June 2007 report by the American Society of Civil Engineers. The flood disaster halted oil production and refining which increased oil prices worldwide.

The article covers the Hurricane Katrina effects by region, within the United States and Canada. The effects of Hurricane Katrina, in late August 2005, were catastrophic and widespread. It was one of the deadliest natural disasters in U.S. history, leaving at least 1,836 people dead, and a further 135 missing. The storm was large and had an effect on several different areas of North America.

Criticism of the government response to Hurricane Katrina was a major political dispute in the United States in 2005 that consisted primarily of condemnations of mismanagement and lack of preparation in the relief effort in response to Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath. Specifically, there was a delayed response to the flooding of New Orleans, Louisiana.

The disaster recovery response to Hurricane Katrina in late 2005 included U.S. federal government agencies such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the United States Coast Guard (USCG), state and local-level agencies, federal and National Guard soldiers, non-governmental organizations, charities, and private individuals. Tens of thousands of volunteers and troops responded or were deployed to the disaster; most in the affected area but also throughout the U.S. at shelters set up in at least 19 states.

This article contains a historical timeline of the events of Hurricane Katrina on August 23–30, 2005 and its aftermath.

Hurricane Katrina struck the United States on August 29, 2005, causing over a thousand deaths and extreme property damage, particularly in New Orleans. The incident affected numerous areas of governance, including disaster preparedness and environmental policy.

New Orleans Union Passenger Terminal (NOUPT) is an intermodal facility in New Orleans, Louisiana, US. Located at 1001 Loyola Avenue, it is served by Amtrak, Greyhound Lines, Megabus, and NORTA with direct connections to the Rampart–St. Claude Streetcar Line.

The Angola Three are three African-American former prison inmates who were held for decades in solitary confinement while imprisoned at Louisiana State Penitentiary. The latter two were indicted in April 1972 for the killing of a prison corrections officer; they were convicted in January 1974. Wallace and Woodfox served more than 40 years each in solitary, the "longest period of solitary confinement in American prison history".

The New Orleans Police Department (NOPD) has primary responsibility for law enforcement in New Orleans, Louisiana. The department's jurisdiction covers all of Orleans Parish, while the city is divided into eight police districts.

Nathan Burl Cain is the commissioner of the Mississippi Department of Corrections and the former warden at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola in West Feliciana Parish, north of Baton Rouge, Louisiana. He worked there for twenty-one years, from January 1995 until his resignation in 2016.

The Louisiana Superdome was used as a "shelter of last resort" for those in New Orleans unable to evacuate from the city when Hurricane Katrina struck on August 29, 2005.

The Department of Public Safety and Corrections (DPS&C) is a state law enforcement agency responsible for the incarceration of inmates and management of facilities at state prisons within the state of Louisiana. The agency is headquartered in Baton Rouge. The agency comprises two major areas: Public Safety Services and Corrections Services. The secretary, who is appointed by the governor of Louisiana, serves as the department's chief executive officer. The Corrections Services deputy secretary, undersecretary, and assistant secretaries for the Office of Adult Services and the Office of Youth Development report directly to the secretary. Headquarters administration consists of centralized divisions that support the management and operations of the adult and juvenile institutions, adult and juvenile probation and parole district offices, and all other services provided by the department.

Prison rape or jail rape is sexual assault of people while they are incarcerated. The phrase is commonly used to describe rape of inmates by other inmates, or to describe rape of inmates by staff. It is a significant if controversial part of what is studied under the wider concept of prison sexuality.

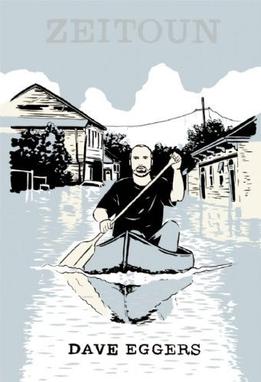

Zeitoun is a nonfiction book written by Dave Eggers and published by McSweeney's in 2009. It tells the story of Abdulrahman Zeitoun, the Syrian-American owner of a painting and contracting company in New Orleans, Louisiana, who chose to ride out Hurricane Katrina in his Uptown home.

Orleans Parish Prison is the city jail for New Orleans, Louisiana. First opened in 1837, it is operated by the Orleans Parish Sheriff's Office. Most of the prisoners—1,300 of the 1,500 or so as of June 2016—are awaiting trial.

Marlowe Parker is an artist who was an inmate at the Louisiana State Penitentiary (Angola) in West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana. Parker exhibited and sold his artwork during the Angola Rodeo art shows. Burl Cain, the warden of Angola, said in 2012 that Parker is "probably one of our best artists." Harry Connick Jr. is one of Parker's fans. Parker named Clementine Hunter and his stepfather, an artist and former Angola prisoner named Gilbert Green, as his influences. Parker is incarcerated due to a 25-year drug-related sentence. Parker had family members living in New Orleans.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brendan McCarthy (June 23, 2010). "Justice system failings in wake of Hurricane Katrina left wounds that remain unhealed". The Times-Picayune . Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- 1 2 "'Camp Greyhound' home to 220 looting suspects". The Washington Times. September 9, 2005. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- 1 2 Greta van Susteren, Burl Cain (September 8, 2005). "New Orleans' Makeshift Jail". Fox News . Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Brandon L. Garrett & Tania Tetlow, Criminal Justice Collapse: The Constitution After Hurricane Katrina, 56 Duke Law Journal 127-178 (2006)

- 1 2 3 4 Marina Sideris, Amnesty Working Group: Amnesty for Prisoners of Katrina. Report of the Critical Resistance, 2007, pages 8-12

- 1 2 Kevin Johnson (8 September 2005). "'Camp Greyhound' outpost of law and order". USA Today . Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Jeff Brady (September 9, 2005). "New Orleans Housing Prisoners in Bus Station". National Public Radio . Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- 1 2 Ed Pilkington (March 11, 2010). "The amazing true story of Zeitoun". The Guardian . Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ↑ Seema Jilani (May 17, 2011). "Haunted by the nightmare of Katrina". The Guardian . Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ↑ "At the Train Station, New Orleans' Newest Jail is Open For Business". KOMO-TV . New Orleans, Louisiana. September 6, 2005. Archived from the original on November 19, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ↑ Susannah Rosenblatt, James Rainey (September 27, 2005). "Katrina Takes a Toll on Truth, News Accuracy". LA Times. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ↑ Peter Berkowitz (September 9, 2005). ""We Went into the Mall and Began 'Looting'":A Letter on Race, Class, and Surviving the Hurricane". Monthly Report online. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Witnesses: New Orleans cops took Rolex watches, jewelry". CNN. September 25, 2005. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ↑ James Gill (November 20, 2016). "James Gill: Still fighting Hurricane Katrina's demons". New Orleans Advocate. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- 1 2 James Fox (April 14, 2011). "No limits to the law in NoLa". New Statesman. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ↑ Dan Berger (August 14, 2009). "Constructing crime, framing disaster. Routines of criminalization and crisis in Hurricane Katrina". Punishment & Society. 11 (4): 491–510. doi:10.1177/1462474509341139. S2CID 143933941.