Hunter is a village in Greene County, New York, United States. The population was 429 at the 2020 census. The village is in the northwestern part of the town of Hunter on New York State Route 23A.

Hunter is a town located in Greene County, New York, United States. The population was 3,035 at the time of the 2020 census. The town contains two villages, one named Hunter on the west, and the second called Tannersville, as well as a number of hamlets such as Haines Falls, Platte Clove, Lanesville and Edgewood. Additionally, there are three residential parks location within town limits: Onteora Park, Twilight Park and Elka Park. The town is on the southern border of Greene County and abuts the towns of Woodstock and Saugerties, located in Ulster County.

A cripple is a person or animal with a physical disability, particularly one who is unable to walk because of an injury or illness. The word was recorded as early as 950 AD, and derives from the Proto-Germanic krupilaz. The German and Dutch words Krüppel and kreupel are cognates.

The disability rights movement is a global social movement that seeks to secure equal opportunities and equal rights for all people with disabilities.

Disability studies is an academic discipline that examines the meaning, nature, and consequences of disability. Initially, the field focused on the division between "impairment" and "disability", where impairment was an impairment of an individual's mind or body, while disability was considered a social construct. This premise gave rise to two distinct models of disability: the social and medical models of disability. In 1999 the social model was universally accepted as the model preferred by the field. However, in recent years, the division between the social and medical models has been challenged. Additionally, there has been an increased focus on interdisciplinary research. For example, recent investigations suggest using "cross-sectional markers of stratification" may help provide new insights on the non-random distribution of risk factors capable of exacerbating disablement processes. Such risk factors can be acute or chronic stressors, which can increase cumulative risk factors The decline of immune function with age and decrease of inter-personal relationships which can impact cognitive function with age.

Independent living (IL), as seen by its advocates, is a philosophy, a way of looking at society and disability, and a worldwide movement of disabled people working for equal opportunities, self-determination, and self-respect. In the context of eldercare, independent living is seen as a step in the continuum of care, with assisted living being the next step.

Edward Verne Roberts was an American activist. He was the first wheelchair user to attend the University of California, Berkeley. He was a pioneering leader of the disability rights movement.

The American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities (ACCD) was, in the mid-1970s to early 1980s, a national consumer-led disability rights organization called, by nationally syndicated columnist Jack Anderson and others, "the handicapped lobby". Created, governed, and administered by individuals with disabilities—which made it a novelty at the time—ACCD rose to prominence in 1977 when it mounted a successful 10-city "sit in" to force the federal government to issue long-overdue rules to carry out Section 504, the world's first disability civil rights provisions. ACCD also earned a place of honor in the disability rights movement when it helped to secure federal funding for what is now a national network of 600 independent living centers and helped to pave the way for accessible Public Transit in the U.S. After a brief and often tumultuous history, ACCD closed its doors in 1983.

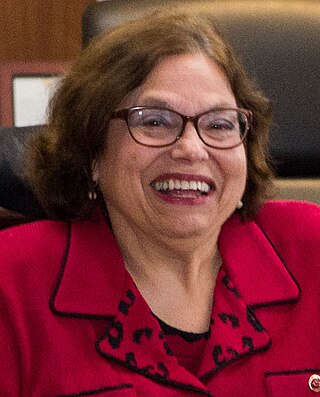

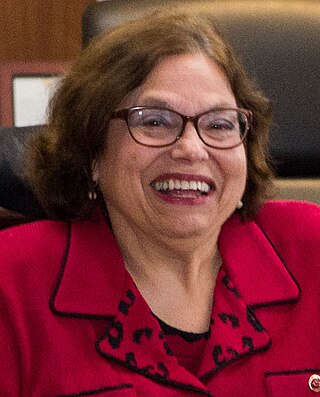

Judith Ellen "Judy" Heumann was an American disability rights activist, known as the "Mother of the Disability Rights Movement". She was recognized internationally as a leader in the disability community. Heumann was a lifelong civil rights advocate for people with disabilities. Her work with governments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), nonprofits, and various other disability interest groups significantly contributed to the development of human rights legislation and policies benefiting children and adults with disabilities. Through her work in the World Bank and the State Department, Heumann led the mainstreaming of disability rights into international development. Her contributions extended the international reach of the independent living movement.

Disabled In Action of Metropolitan New York (DIA) is a civil rights organization, based in New York City, committed to ending discrimination against people with disabilities through litigation and demonstrations. It was founded in 1970 by Judith E. Heumann and her friends Denise McQuade, Bobbi Linn, Frieda Tankas, Fred Francis, Pat Figueroa, possibly Larry Weissberger, Susan Marcus, Jimmy Lynch and Roni Stier (all of whom were disabled). Heumann had met some of the others at Camp Jened, a camp for children with disabilities. Disabled In Action is a democratic, not-for-profit, tax-exempt, membership organization. Disabled In Action consists primarily of and is directed by people with disabilities.

The depiction of disability in the media plays a major role in molding the public perception of disability. Perceptions portrayed in the media directly influence the way people with disabilities are treated in current society. "[Media platforms] have been cited as a key site for the reinforcement of negative images and ideas in regard to people with disabilities."

Lives Worth Living is a 2011 documentary film directed by Eric Neudel and produced by Alison Gilkey, and broadcast by PBS through ITVS, as part of the Independent Lens series. The film is the first television chronicle of the history of the American disability rights movement from the post-World War II era until the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990.

Dom Ławniczak Evans is a Polish-Irish-American filmmaker, streamer, public speaker, and social activist who focuses on LGBT rights and disability rights.

The 504 Sit-in was a disability rights protest that began on April 5, 1977. People with disabilities and the disability community occupied federal buildings in the United States in order to push the issuance of long-delayed regulations regarding Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Prior to the 1990 enactment of the Americans with Disabilities Act, the Rehabilitation Act was the most important disability rights legislation in the United States.

Crip, slang for cripple, is a term in the process of being reclaimed by disabled people. Wright State University suggests that the current community definition of crip includes people who experience any form of disability, such as one or more impairments with physical, mental, learning, and sensory, though the term primarily targets physical and mobility impairment. People might identify as a crip for many reasons. Some of these reasons are to show pride, to talk about disability rights, or avoid ranking types of disability.

Marilyn E. Saviola was an American disability rights activist, executive director of the Center for the Independence of the Disabled in New York from 1983 to 1999, and vice president of Independence Care System after 2000. Saviola, a polio survivor from Manhattan, New York, is known nationally within the disability rights movement for her advocacy for people with disabilities and had accepted many awards and honors for her work.

Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution is a 2020 American documentary film directed, written, and co-produced by Nicole Newnham and James LeBrecht. Barack and Michelle Obama served as executive producers under their Higher Ground Productions banner.

James LeBrecht is a filmmaker, sound designer, and disability rights activist. He currently lives in Oakland, California.

Stacey Park Milbern was a Korean-American Disability Justice activist. She helped create the Disability Justice movement and advocated for fair treatment of disabled people.