Hate speech is a legal term with varied meaning. It has no single, consistent definition. It is defined by the Cambridge Dictionary as "public speech that expresses hate or encourages violence towards a person or group based on something such as race, religion, sex, or sexual orientation". The Encyclopedia of the American Constitution states that hate speech is "usually thought to include communications of animosity or disparagement of an individual or a group on account of a group characteristic such as race, color, national origin, sex, disability, religion, or sexual orientation". There is no single definition of what constitutes "hate" or "disparagement". Legal definitions of hate speech vary from country to country.

Defamation is a communication that injures a third party's reputation and causes a legally redressable injury. The precise legal definition of defamation varies from country to country. It is not necessarily restricted to making assertions that are falsifiable, and can extend to concepts that are more abstract than reputation – like dignity and honour. In the English-speaking world, the law of defamation traditionally distinguishes between libel and slander. It is treated as a civil wrong, as a criminal offence, or both.

Strategic lawsuits against public participation, or strategic litigation against public participation, are lawsuits intended to censor, intimidate, and silence critics by burdening them with the cost of a legal defense until they abandon their criticism or opposition.

Although Australia is considered to have, in general, both freedom of speech and a free and independent media, certain subject-matter is subject to various forms of government censorship. These include matters of national security, judicial non-publication or suppression orders, defamation law, the federal Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth), film and literature classification, and advertising restrictions.

Censorship in the United Kingdom was at different times more or less widely applied to various forms of expression such as the press, cinema, entertainment venues, literature, theatre and criticism of the monarchy. While there is no general right to free speech in the UK, British citizens have a negative right to freedom of expression under the common law, and since 1998, freedom of expression is guaranteed according to Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, as applied in British law through the Human Rights Act.

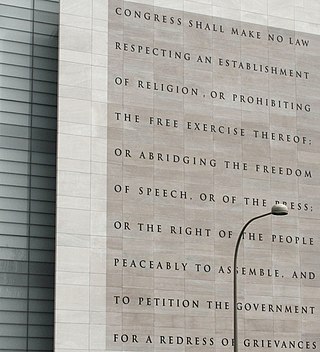

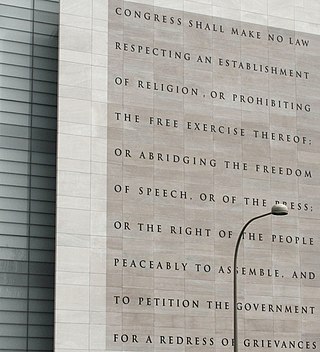

In the United States, freedom of speech and expression is strongly protected from government restrictions by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, many state constitutions, and state and federal laws. Freedom of speech, also called free speech, means the free and public expression of opinions without censorship, interference and restraint by the government. The term "freedom of speech" embedded in the First Amendment encompasses the decision what to say as well as what not to say. The Supreme Court of the United States has recognized several categories of speech that are given lesser or no protection by the First Amendment and has recognized that governments may enact reasonable time, place, or manner restrictions on speech. The First Amendment's constitutional right of free speech, which is applicable to state and local governments under the incorporation doctrine, prevents only government restrictions on speech, not restrictions imposed by private individuals or businesses unless they are acting on behalf of the government. However, It can be restricted by time, place and manner in limited circumstances. Some laws may restrict the ability of private businesses and individuals from restricting the speech of others, such as employment laws that restrict employers' ability to prevent employees from disclosing their salary to coworkers or attempting to organize a labor union.

Prior restraint is censorship imposed, usually by a government or institution, on expression, that prohibits particular instances of expression. It is in contrast to censorship that establishes general subject matter restrictions and reviews a particular instance of expression only after the expression has taken place.

Section 2 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms ("Charter") is the section of the Constitution of Canada that lists what the Charter calls "fundamental freedoms" theoretically applying to everyone in Canada, regardless of whether they are a Canadian citizen, or an individual or corporation. These freedoms can be held against actions of all levels of government and are enforceable by the courts. The fundamental freedoms are freedom of expression, freedom of religion, freedom of thought, freedom of belief, freedom of peaceful assembly and freedom of association.

A speech code is any rule or regulation that limits, restricts, or bans speech beyond the strict legal limitations upon freedom of speech or press found in the legal definitions of harassment, slander, libel, and fighting words. Such codes are common in the workplace, in universities, and in private organizations. The term may be applied to regulations that do not explicitly prohibit particular words or sentences. Speech codes are often applied for the purpose of suppressing hate speech or forms of social discourse thought to be disagreeable to the implementers.

Funding Evil: How Terrorism is Financed and How to Stop It is a book written by counterterrorism researcher Dr. Rachel Ehrenfeld, director of the American Center for Democracy and the Economic Warfare Institute. It was published by Bonus Books of Los Angeles, California in August 2003.

Canadian defamation law refers to defamation law as it stands in both common law and civil law jurisdictions in Canada. As with most Commonwealth jurisdictions, Canada follows English law on defamation issues.

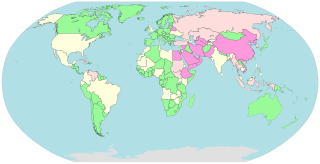

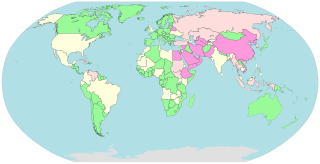

Freedom of speech is the concept of the inherent human right to voice one's opinion publicly without fear of censorship or punishment. "Speech" is not limited to public speaking and is generally taken to include other forms of expression. The right is preserved in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and is granted formal recognition by the laws of most nations. Nonetheless, the degree to which the right is upheld in practice varies greatly from one nation to another. In many nations, particularly those with authoritarian forms of government, overt government censorship is enforced. Censorship has also been claimed to occur in other forms and there are different approaches to issues such as hate speech, obscenity, and defamation laws.

California Education Code 48907 (1977), also known as the California Student Free Expression Law, acts as a counter to the Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier (1988) Supreme Court ruling, which limited the freedom of speech granted to public high school newspapers. The Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier decision held that public school curricular student newspapers that have not been established as "forums for student expression" are subject to a lower level of First Amendment protection than independent student expression or newspapers established as forums for student expression. Ed Code 48907 affirms the right of high school newspapers to publish whatever they choose, so long as the content isn't explicitly obscene, libelous, or slanderous, and doesn’t incite students to violate any laws or school regulations. The newspaper content must also pass the minimal disruption test set forth in the Supreme Court ruling on Tinker v. Des Moines (1969). In contrast with Hazelwood, which limited First Amendment protection to only those high school newspapers that had, through practice or policy, been established as forums for student expression, Ed Code 48907 affirms the right of all newspapers to the freedom of expression.

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recognised as a human right in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and international human rights law by the United Nations. Many countries have constitutional law that protects free speech. Terms like free speech, freedom of speech, and freedom of expression are used interchangeably in political discourse. However, in a legal sense, the freedom of expression includes any activity of seeking, receiving, and imparting information or ideas, regardless of the medium used.

Speech crimes are certain kinds of speech that are criminalized by promulgated laws or rules. Criminal speech is a direct preemptive restriction on freedom of speech, and the broader concept of freedom of expression.

Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition, 535 U.S. 234 (2002), is a U.S. Supreme Court case that struck down two overbroad provisions of the Child Pornography Prevention Act of 1996 because they abridged "the freedom to engage in a substantial amount of lawful speech". The case was brought against the U.S. government by the Free Speech Coalition, a "California trade association for the adult-entertainment industry", along with Bold Type, Inc., a "publisher of a book advocating the nudist lifestyle"; Jim Gingerich, who paints nudes; and Ron Raffaelli, a photographer who specialized in erotic images. By striking down these two provisions, the Court rejected an invitation to increase the amount of speech that would be categorically outside the protection of the First Amendment.

Freedom of expression in Canada is protected as a "fundamental freedom" by section 2 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms; however, in practice the Charter permits the government to enforce "reasonable" limits censoring speech. Hate speech, obscenity, and defamation are common categories of restricted speech in Canada. During the 1970 October Crisis, the War Measures Act was used to limit speech from the militant political opposition.

British Chiropractic Association (BCA) v Singh was an influential libel action in England and Wales, widely credited as a catalytic event in the libel reform campaign which saw all parties at the 2010 general election making manifesto commitments to libel reform, and passage of the Defamation Act 2013 by the British Parliament in April 2013.

This list of Internet censorship and surveillance in Africa provides information on the types and levels of Internet censorship and surveillance that is occurring in countries in Africa.

Collateral censorship is a type of censorship where the fear of legal liability is used to incentivize a private party who is acting as an intermediary to censor the speech of another private party. Examples of intermediaries include publishers, journalists, and online service providers. Regardless of the merits of the speech in question, holding intermediaries liable may induce them to censor a large amount of additional speech in an attempt to avoid liability. Also, an intermediary is likely to be more willing to censor than the original speaker would be, since it is not as invested in promoting the speech in question.