The history of Madagascar is distinguished clearly by the early isolation of the landmass from the ancient supercontinent of Pangaea, containing amongst others the African continent and the Indian subcontinent, and by the island's late colonization by human settlers from the Sunda islands and from East Africa. These two factors facilitated the evolution and survival of thousands of endemic plant and animal species, some of which have gone extinct or are currently threatened with extinction. Trade in the Indian Ocean at the time of first colonization of Madagascar was dominated by Indonesian ships, probably of Borobudur ship and K'un-lun po types.

Antananarivo, also known by its colonial shorthand form Tana, is the capital and largest city of Madagascar. The administrative area of the city, known as Antananarivo-Renivohitra, is the capital of Analamanga region. The city sits at 1,280 m (4,199 ft) above sea level in the center of the island, the highest national capital by elevation among the island countries. It has been the country's largest population center since at least the 18th century. The presidency, National Assembly, Senate and Supreme Court are located there, as are 21 diplomatic missions and the headquarters of many national and international businesses and NGOs. It has more universities, nightclubs, art venues, and medical services than any city on the island. Several national and local sports teams, including the championship-winning national rugby team, the Makis, are based here.

Radama I "the Great" (1793–1828) was the first Malagasy sovereign to be recognized as King of Madagascar (1810–1828) by a European state, Great Britain. He came to power at the age of 17 following the death of his father, King Andrianampoinimerina.

Ranavalona I, also known as Ranavalo-Manjaka I and the “Mad Monarch of Madagascar” was sovereign of the Kingdom of Madagascar from 1828 to 1861. After positioning herself as queen following the death of her young husband, Radama I, Ranavalona pursued a policy of isolationism and self-sufficiency, reducing economic and political ties with European powers, repelling a French attack on the coastal town of Foulpointe, and taking vigorous measures to eradicate the small but growing Malagasy Christian movement initiated under Radama I by members of the London Missionary Society.

Radama II was the son and heir of Queen Ranavalona I and ruled from 1861 to 1863 over the Kingdom of Madagascar, which controlled virtually the entire island. Radama's rule, although brief, was a pivotal period in the history of the Kingdom of Madagascar. Under the unyielding and often harsh 33-year rule of his mother, Queen Ranavalona I, Madagascar had successfully preserved its cultural and political independence from European colonial designs. Rejecting the queen's policy of isolationism and persecution of Christians, Radama II permitted religious freedom and re-opened Madagascar to European influence. Under the terms of the Lambert Charter, which Radama secretly contracted in 1855 with French entrepreneur Joseph-François Lambert while Ranavalona still ruled, the French were awarded exclusive rights to the exploitation of large tracts of valuable land and other lucrative resources and projects. This agreement, which was later revoked by Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony, was key to establishing France's claim over Madagascar as a protectorate and, in 1896, as a colony.

Rasoherina was Queen of Madagascar from 1863 to 1868, succeeding her husband Radama II following his presumed assassination.

Ranavalona II was Queen of Madagascar from 1868 to 1883, succeeding Queen Rasoherina, her first cousin. She is best remembered for Christianizing the royal court during her reign.

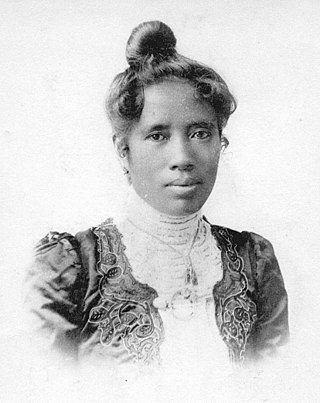

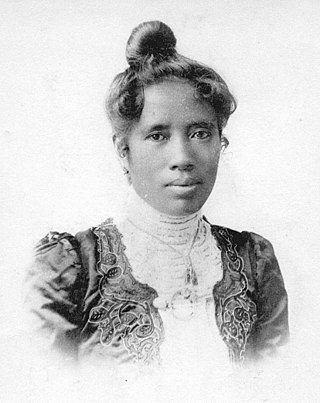

Ranavalona III was the last sovereign of the Kingdom of Madagascar. She ruled from 30 July 1883 to 28 February 1897 in a reign marked by ultimately futile efforts to resist the colonial designs of the government of France. As a young woman, she was selected from among several Andriana qualified to succeed Queen Ranavalona II upon her death. Like both preceding queens, Ranavalona entered a political marriage with a member of the Hova elite named Rainilaiarivony, who largely oversaw the day-to-day governance of the kingdom and managed its foreign affairs in his role as prime minister. Ranavalona tried to stave off colonization by strengthening trade and diplomatic relations with foreign powers throughout her reign, but French attacks on coastal port towns and an assault on the capital city of Antananarivo led to the capture of the royal palace in 1895, ending the sovereignty and political autonomy of the centuries-old kingdom.

The Merina people are the largest ethnic group in Madagascar. They are the "highlander" Malagasy ethnic group of the African island and one of the country's eighteen official ethnic groups. Their origins are mixed, predominantly with Austronesians arriving before the 5th century AD, then many centuries later with mostly Bantu Africans, but also some other ethnic groups. They speak the Merina dialect of the official Malagasy language of Madagascar.

The Malagasy Protectorate was a French protectorate in what is now Madagascar. Through the protectorate, France attempted to control the foreign affairs of the Kingdom of Imerina through its representative at Antananarivo. France declared the island a protectorate in 1882 after reaching an agreement with Britain, which had been the first European power to establish a lasting influence and presence on the island that dated back to the arrival of London Missionary Society missionaries around 1820; Britain agreed to sanction French claims to Madagascar in exchange for French recognition of its claims to Zanzibar. The French justified the establishment of a protectorate on the basis of land claims over outlying islands like Nosy Be and Nosy Boraha and a treaty signed with a local leader of the western coastal Sakalava people. It was further justified through documents signed by King Radama II, including a letter he was possibly tricked into signing that entreated Napoleon III to support a coup d'état against Ranavalona I, and land ownership agreements with French industrialist Joseph-François Lambert that were revoked upon Radama's assassination in 1863. It ended in 1897 as Madagascar became a French colony.

Rainilaiarivony was a Malagasy politician who served as the prime minister of Madagascar from 1864 to 1895, succeeding his older brother Rainivoninahitriniony, who had held the post for thirteen years. His career mirrored that of his father Rainiharo, a renowned military man who became prime minister during the reign of Queen Ranavalona I.

The Franco-Hova Wars, also known as the Franco-Malagasy Wars, were two French military interventions in Madagascar between 1883 and 1896 that overthrew the ruling monarchy of the Merina Kingdom, and resulted in Madagascar becoming a French colony. The term "Hova" referred to a social class within the Merina class structure.

The Rova of Antananarivo is a royal palace complex (rova) in Madagascar that served as the home of the sovereigns of the Kingdom of Imerina in the 17th and 18th centuries, as well as of the rulers of the Kingdom of Madagascar in the 19th century. Its counterpart is the nearby fortified village of Ambohimanga, which served as the spiritual seat of the kingdom in contrast to the political significance of the Rova in the capital. Located in the central highland city of Antananarivo, the Rova occupies the highest point on Analamanga, formerly the highest of Antananarivo's many hills. Merina king Andrianjaka, who ruled Imerina from around 1610 until 1630, is believed to have captured Analamanga from a Vazimba king around 1610 or 1625 and erected the site's first fortified royal structure. Successive Merina kings continued to rule from the site until the fall of the monarchy in 1896, frequently restoring, modifying or adding royal structures within the compound to suit their needs.

Education in Madagascar has a long and distinguished history. Formal schooling began with medieval Arab seafarers, who established a handful of Islamic primary schools (kuttabs) and developed a transcription of the Malagasy language using Arabic script, known as sorabe. These schools were short-lived, and formal education was only to return under the 19th-century Kingdom of Madagascar when the support of successive kings and queens produced the most developed public school system in precolonial Sub-Saharan Africa. However, formal schools were largely limited to the central highlands around the capital of Antananarivo and were frequented by children of the noble class andriana. Among other segments of the island's population, traditional education predominated through the early 20th century. This informal transmission of communal knowledge, skills and norms was oriented toward preparing children to take their place in a social hierarchy dominated by community elders and particularly the ancestors (razana), who were believed to oversee and influence events on earth.

The KingdomofMerina, or Kingdom of Madagascar, officially the Kingdom of Imerina, was a pre-colonial state off the coast of Southeast Africa that, by the 18th century, dominated most of what is now Madagascar. It spread outward from Imerina, the Central Highlands region primarily inhabited by the Merina ethnic group with a spiritual capital at Ambohimanga and a political capital 24 km (15 mi) west at Antananarivo, currently the seat of government for the modern state of Madagascar. The Merina kings and queens who ruled over greater Madagascar in the 19th century were the descendants of a long line of hereditary Merina royalty originating with Andriamanelo, who is traditionally credited with founding Imerina in 1540.

The First Madagascar expedition was the beginning of the Franco-Hova War and consisted of a French military expedition against the Merina Kingdom on the island of Madagascar in 1883. It was followed by the Second Madagascar expedition in 1895.

James Cameron (1799–1875) was a 19th-century British artisan missionary with a background in carpentry who, over the course of twenty-three years of service in Madagascar with the London Missionary Society, played a major role in the Christianisation and industrialisation of that island state, then under the rule of the Merina monarchy.

David Griffiths, was a Welsh Christian missionary and translator in Madagascar. He translated the Bible and other books into the Malagasy language. The Malagasy Bible of 1835 was among the first Bibles to be printed in an African language.

The Menalamba rebellion was an uprising in Madagascar by the Sakalava people that emerged in central Madagascar in response to the French capture of the royal palace in the capital city of Antananarivo in September 1895. it spread rapidly in 1896, threatening the capital, but French forces were successful in securing the surrender of many rebel groups in 1897. Elements of the rebellion continued sporadically until 1903.

St. Lawrence Anglican Cathedral Ambohimanoro is an Anglican cathedral in Madagascar's capital of Antananarivo. Located in the upper part of the city, the cathedral was built on the hill of Ambohimanoro, near the Andohalo square, and has now been designated as a national heritage by the Malagasy government. It is one of the first permanent Anglican churches built on the island.

![Ambatonakanga Church, Madagascar (London LMS], 1869, p. 48) Ambatonakanga Church, Madagascar (LMS, 1869, p.48).jpg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/27/Ambatonakanga_Church%2C_Madagascar_%28LMS%2C_1869%2C_p.48%29.jpg/220px-Ambatonakanga_Church%2C_Madagascar_%28LMS%2C_1869%2C_p.48%29.jpg)