The Slavey are a First Nations indigenous peoples of the Dene group, indigenous to the Great Slave Lake region, in Canada's Northwest Territories, and extending into northeastern British Columbia and northwestern Alberta.

The Chipewyan are a Dene Indigenous Canadian people of the Athabaskan language family, whose ancestors are identified with the Taltheilei Shale archaeological tradition. They are part of the Northern Athabascan group of peoples, and hail from what is now Western Canada.

Chipewyan or Dënesųłinë́, often simply called Dëne, is the language spoken by the Chipewyan people of northwestern Canada. It is categorized as part of the Northern Athabaskan language family. It has nearly 12,000 speakers in Canada, mostly in Saskatchewan, Alberta, Manitoba and the Northwest Territories. It has official status only in the Northwest Territories, alongside 8 other aboriginal languages: Cree, Tlicho, Gwich'in, Inuktitut, Inuinnaqtun, Inuvialuktun, North Slavey and South Slavey.

The Dene people are an indigenous group of First Nations who inhabit the northern boreal and Arctic regions of Canada. The Dene speak Northern Athabaskan languages. Dene is the common Athabaskan word for "people". The term "Dene" has two uses:

A tribal council is an association of First Nations bands in Canada, generally along regional, ethnic or linguistic lines.

First Nations in Alberta are a group of people who live in the Canadian province of Alberta. The First Nations are peoples recognized as Indigenous peoples or Plains Indians in Canada excluding the Inuit and the Métis. According to the 2011 Census, a population of 116,670 Albertans self-identified as First Nations. Specifically there were 96,730 First Nations people with registered Indian Status and 19,945 First Nations people without registered Indian Status. Alberta has the third largest First Nations population among the provinces and territories. From this total population, 47.3% of the population lives on an Indian reserve and the other 52.7% live in urban centres. According to the 2011 Census, the First Nations population in Edmonton totalled at 31,780, which is the second highest for any city in Canada. The First Nations population in Calgary, in reference to the 2011 Census, totalled at 17,040. There are 48 First Nations or "bands" in Alberta, belonging to nine different ethnic groups or "tribes" based on their ancestral languages.

Patuanak is a community in northern Saskatchewan, Canada. It is the administrative headquarters of the Dene First Nations reserve near Churchill River and the north end of Lac Île-à-la-Crosse. In Dene, it sounds similar to Boni Cheri (Bëghą́nı̨ch’ërë).

Treaty 10 was an agreement established beginning 19 August 1906, between King Edward VII and various First Nation band governments in northern Saskatchewan and a small portion of eastern Alberta. There were no Alberta-based First Nations groups signing on, but there were two First Nation bands from Manitoba, despite their location outside the designated treaty area. It is notable that despite appeals from peoples of unceded areas of Northern Manitoba and the Northwest Territories for treaty negotiations to begin, the government did not enter into the treaty process for almost 20 years. In 1879, Natives of Stanley, Lac la Ronge, and Pelican Narrows petitioned for a treaty due to the threat of starvation. In 1905, the granting of Saskatchewan with Provincial status galvanized the government to settle the issue of land rights in order to free up land for future government use. The Canadian government signed Treaty 10 with the First Nations. The territory covered almost 220,000 square kilometers and included Cree and Chipewyan First Nation tribe population. Like the other treaties, it requires the First Nations to surrender their Aboriginal Title for land claim and rights.

The Chipewyan Prairie First Nation is a First Nations band government located in northeast Alberta south of Fort McMurray.

The Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation is a band government. It represents local people of the Denesuline (Chipewyan) ethnic group. It controls eight Indian reserves: Chipewyan 201 and Chipewyan 201A through Chipewyan 201G, near Fort Chipewyan, Alberta. The band is party to Treaty 8, and is a member of the Athabasca Tribal Council.

The Northlands Denesuline First Nation is a First Nations band government in northwestern Manitoba, Canada. This Dene or Denesuline population were part of a larger group once called the "Caribou-eaters".

Black Lake is a Denesuline First Nations band government in the boreal forest of northern Saskatchewan, Canada. It is located on the northwest shore of Black Lake where the Fond du Lac River leaves the lake to flow to Lake Athabasca.

Hatchet Lake Denesuline Nation is a Denesuline First Nation in northern Saskatchewan. The main settlement, Wollaston Lake, is an unincorporated community on Wollaston Lake in the boreal forest of north-eastern Saskatchewan, Canada.

Thanadelthur "Thanadeltth'er" was a woman of the Chipewyan Dënesųłı̨ne nation who served as a guide and interpreter for the Hudson's Bay Company. She was instrumental in forging a peace agreement between the Dënesųłı̨ne (Chipewyan) and the Cree people. She was trilingual, able to speak English, Chipewyan, and Cree.

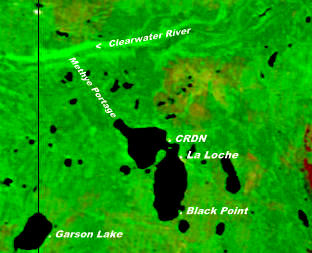

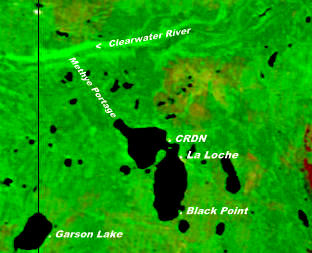

The Clearwater River Dene Nation is a Dene First Nations band government in the boreal forest area of northern Saskatchewan, Canada. It maintains offices in the village of Clearwater River situated on the eastern shore of Lac La Loche. The Clearwater River Dene Nation reserve of Clearwater River shares its southern border with the village of La Loche.

The Buffalo River Dene Nation is a Dene First Nations band government in Saskatchewan, Canada. The band's main community, Dillon, is located on the western shore of Peter Pond Lake at the mouth of the Dillon River, and is accessed by Highway 925 from Highway 155.

The Beaver Lake Cree Nation is a First Nations band government located 105 kilometres (65 mi) northeast of Edmonton, Alberta, representing people of the Cree ethno-linguistic group in the area around Lac La Biche, Alberta, where the band office is currently located. Their treaty area is Treaty 6. The Intergovernmental Affairs office consults with persons on the Government treaty contacts list. There are two parcels of land reserved for the band by the Canadian Crown, Beaver Lake Indian Reserve No. 131 and Blue Quills First Nation Indian Reserve. The latter reserve is shared by six bands; Beaver Lake Cree Nations, Cold Lake First Nations, Frog Lake First Nation, Heart Lake First Nation, Kehewin Cree Nation, Saddle Lake Cree Nation.

The English River Dene Nation is a Dene First Nation band government in Patuanak, Saskatchewan, Canada. Their reserve is in the northern section of the province. Its territories are in the boreal forest of the Canadian Shield. This First Nation is a member of the Meadow Lake Tribal Council (MLTC).

Birch Narrows Dene Nation is a Dene First Nation band government in the boreal forest region of northern Saskatchewan, Canada. It is affiliated with the Meadow Lake Tribal Council (MLTC).

Smith's Landing First Nation is a band government headquartered at Fort Smith, Northwest Territories, Canada. Members of the band call themselves, in the Dene Suline language, the Thebati Dene Suhne.