John Hancock was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He is remembered for his large and stylish signature on the United States Declaration of Independence, so much so that in the United States, John Hancock or Hancock has become a colloquialism for a person's signature. He also signed the Articles of Confederation, and used his influence to ensure that Massachusetts ratified the United States Constitution in 1788.

The Declaration of Independence, formally titled The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, is the founding document of the United States. On July 4, 1776, it was adopted unanimously by the 56 delegates to the Second Continental Congress, who had convened at the Pennsylvania State House, later renamed Independence Hall, in the colonial era capital of Philadelphia. The declaration explains to the world why the Thirteen Colonies regarded themselves as independent sovereign states no longer subject to British colonial rule.

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. The Continental Congress refers to both the First and Second Congresses of 1774–1781 and at the time, also described the Congress of the Confederation of 1781–1789. The Confederation Congress operated as the first federal government until being replaced following ratification of the U.S. Constitution. Until 1785, the Congress met predominantly at what is today Independence Hall in Philadelphia, though it was relocated temporarily on several occasions during the Revolutionary War and the fall of Philadelphia.

1776 is a musical with music and lyrics by Sherman Edwards and a book by Peter Stone. The show is based on the events leading up to the signing of the Declaration of Independence, telling a story of the efforts of John Adams to persuade his colleagues to vote for American independence and to sign the document. The show premiered on Broadway in 1969 where it received acclaim and won three Tony Awards, including Best Musical. The original production starred William Daniels as Adams, Ken Howard as Thomas Jefferson and Howard Da Silva as Benjamin Franklin.

The Olive Branch Petition was adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 5, 1775, and signed on July 8 in a final attempt to avoid war between Great Britain and the Thirteen Colonies in America. The Congress had already authorized the invasion of Canada more than a week earlier, but the petition affirmed American loyalty to Great Britain and entreated King George III to prevent further conflict. It was followed by the July 6 Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms, however, which made its success unlikely in London. In August 1775, the colonies were formally declared to be in rebellion by the Proclamation of Rebellion, and the petition was rejected by the British government; King George had refused to read it before declaring the colonists traitors.

The Second Continental Congress was the late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolution and the Revolutionary War, which established American independence from the British Empire. The Congress constituted a new federation that it first named the United Colonies, and in 1776, renamed the United States of America. The Congress began convening in Philadelphia, on May 10, 1775, with representatives from 12 of the 13 colonies, after the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

The Founding Fathers of the United States, commonly referred to as the Founding Fathers, were a group of late-18th-century American revolutionary leaders who united the Thirteen Colonies, oversaw the War of Independence from Great Britain, established the United States of America, and crafted a framework of government for the new nation.

Independence Day, known colloquially as the Fourth of July, is a federal holiday in the United States commemorating the Declaration of Independence, which was ratified by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, establishing the United States of America.

Timothy Matlack was an American politician, military officer and businessman who was chosen in 1776 to inscribe the original United States Declaration of Independence on vellum.. A brewer and beer bottler who emerged as a popular and powerful leader in the American Revolutionary War, Matlack served as Secretary of Pennsylvania during the conflict and a delegate to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia in 1780. Matlack was known for his excellent penmanship, and his handwritten copy of the Declaration is on public display in the Rotunda of the Charters of Freedom at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C.

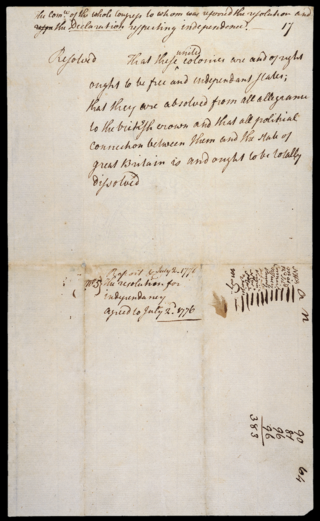

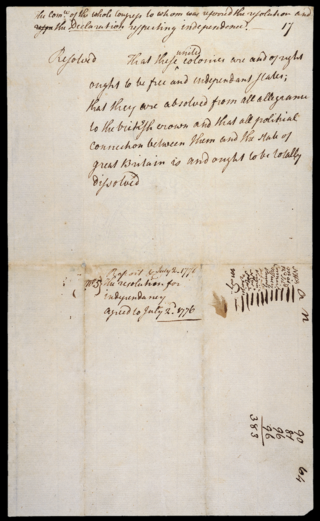

The Lee Resolution, also known as "The Resolution for Independence", was the formal assertion passed by the Second Continental Congress on July 2, 1776, which resolved that the Thirteen Colonies, then referred to as the United Colonies, were "free and independent States" and separate from the British Empire, which created what became the United States. News of this act was published that evening in The Pennsylvania Evening Post and the next day in The Pennsylvania Gazette. The Declaration of Independence, which officially announced and explained the case for independence, was approved two days later, on July 4, 1776.

John Dunlap was an early American printer who emigrated from Ulster, Ireland and who printed the first copies of the United States Declaration of Independence and was one of the most successful Irish/American printers of his era. He served in the Continental Army under George Washington during the American Revolutionary War.

The United Colonies was the name used by the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia to describe the proto-state comprising the Thirteen Colonies in 1775 and 1776, before and as independence was declared. Continental currency banknotes displayed the name 'The United Colonies' from May 1775 until February 1777, and the name was being used as a colloquial phrase to refer to the colonies as a whole before the Second Congress met, although the precise place or date of its origin is unknown.

Declaration of Independence is a 12-by-18-foot oil-on-canvas painting by the American artist John Trumbull depicting the presentation of the draft of the Declaration of Independence to Congress. It was based on a much smaller version of the same scene, presently held by the Yale University Art Gallery. Trumbull painted many of the figures in the picture from life, and visited Independence Hall to depict the chamber where the Second Continental Congress met. The oil-on-canvas work was commissioned in 1817, purchased in 1819, and placed in the United States Capitol rotunda in 1826.

1776 is a 1972 American historical musical comedy drama film directed by Peter H. Hunt and written by Peter Stone, based on his book for the 1969 Broadway musical of the same name, with music and lyrics by Sherman Edwards. Set in Philadelphia in the summer of 1776, it is a fictionalized account of the events leading up to the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The film stars William Daniels, Howard da Silva, Donald Madden, John Cullum, Ken Howard and Blythe Danner.

The physical history of the United States Declaration of Independence spans from its original drafting in 1776 into the discovery of historical documents in modern time. This includes a number of drafts, handwritten copies, and published broadsides. The Declaration of Independence states that the Thirteen Colonies were now the "United Colonies" which "are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States"; and were no longer a part of the British Empire.

The signing of the United States Declaration of Independence occurred primarily on August 2, 1776, at the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia, later to become known as Independence Hall. The 56 delegates to the Second Continental Congress represented the 13 colonies, 12 of which voted to approve the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. The New York delegation abstained because they had not yet received instructions from Albany to vote for independence. The Declaration proclaimed the signatory colonies were now "free and independent States", no longer colonies of the Kingdom of Great Britain and, thus, no longer a part of the British Empire. The signers’ names are grouped by state, with the exception of John Hancock, as President of the Continental Congress; the states are arranged geographically from south to north, with Button Gwinnett from Georgia first, and Matthew Thornton from New Hampshire last.

The Memorial to the 56 Signers of the Declaration of Independence is a memorial depicting the signatures of the 56 signatories to the United States Declaration of Independence. It is located in the Constitution Gardens on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The memorial is accessible to the public by crossing a wooden bridge onto a small island set in the lake between Constitution Avenue and the Reflecting Pool, not far from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

The Augusta Declaration, or the Memorial of Augusta County Committee, May 10, 1776, was a statement presented to the Fifth Virginia Convention in Williamsburg, Virginia on May 10, 1776. The Declaration announced the necessity of the Thirteen Colonies to form a permanent and independent union of states and national government separate from Great Britain, with whom the Colonies were at war.

The United States Constitution was first printed by Dunlap & Claypoole in 1787, during the Constitutional Convention. From the original printing, 13 original copies are known to exist.

In the first half of 1776, the Thirteen Colonies individually declared independence from the British Empire. On July 4, the Declaration of Independence marked the beginning of the United States.