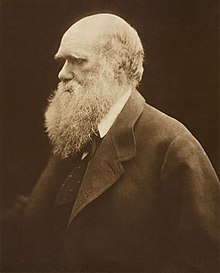

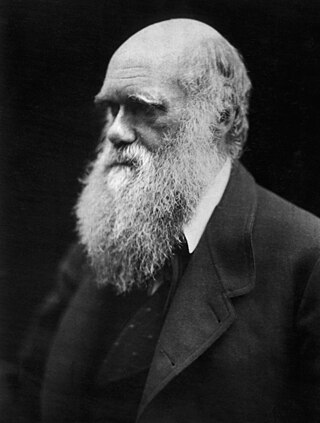

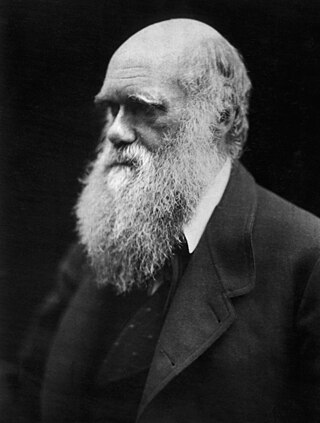

Darwinism is a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others, stating that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural selection of small, inherited variations that increase the individual's ability to compete, survive, and reproduce. Also called Darwinian theory, it originally included the broad concepts of transmutation of species or of evolution which gained general scientific acceptance after Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, including concepts which predated Darwin's theories. English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley coined the term Darwinism in April 1860.

Evolutionism is a term used to denote the theory of evolution. Its exact meaning has changed over time as the study of evolution has progressed. In the 19th century, it was used to describe the belief that organisms deliberately improved themselves through progressive inherited change (orthogenesis). The teleological belief went on to include cultural evolution and social evolution. In the 1970s, the term "Neo-Evolutionism" was used to describe the idea that "human beings sought to preserve a familiar style of life unless change was forced on them by factors that were beyond their control."

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a scientific discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from an evolutionary perspective. This subfield of anthropology systematically studies human beings from a biological perspective.

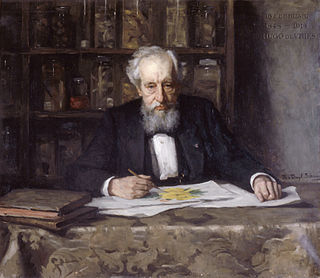

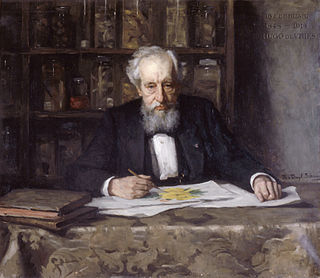

The modern synthesis was the early 20th-century synthesis of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution and Gregor Mendel's ideas on heredity into a joint mathematical framework. Julian Huxley coined the term in his 1942 book, Evolution: The Modern Synthesis.

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley was an English evolutionary biologist, eugenicist, and internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentieth century modern synthesis. He was secretary of the Zoological Society of London (1935–1942), the first Director of UNESCO, a founding member of the World Wildlife Fund, the president of the British Eugenics Society (1959-1962), and the first President of the British Humanist Association.

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes that produced the diversity of life on Earth. It is also defined as the study of the history of life forms on Earth. Evolution holds that all species are related and gradually change over generations. In a population, the genetic variations affect the phenotypes of an organism. These changes in the phenotypes will be an advantage to some organisms, which will then be passed onto their offspring. Some examples of evolution in species over many generations are the peppered moth and flightless birds. In the 1930s, the discipline of evolutionary biology emerged through what Julian Huxley called the modern synthesis of understanding, from previously unrelated fields of biological research, such as genetics and ecology, systematics, and paleontology.

Darwin Day is a celebration to commemorate the birthday of Charles Darwin on 12 February 1809. The day is used to highlight Darwin's contributions to science and to promote science in general. Darwin Day is celebrated around the world.

Orthogenesis, also known as orthogenetic evolution, progressive evolution, evolutionary progress, or progressionism, is an obsolete biological hypothesis that organisms have an innate tendency to evolve in a definite direction towards some goal (teleology) due to some internal mechanism or "driving force". According to the theory, the largest-scale trends in evolution have an absolute goal such as increasing biological complexity. Prominent historical figures who have championed some form of evolutionary progress include Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and Henri Bergson.

Sociocultural evolution, sociocultural evolutionism or social evolution are theories of sociobiology and cultural evolution that describe how societies and culture change over time. Whereas sociocultural development traces processes that tend to increase the complexity of a society or culture, sociocultural evolution also considers process that can lead to decreases in complexity (degeneration) or that can produce variation or proliferation without any seemingly significant changes in complexity (cladogenesis). Sociocultural evolution is "the process by which structural reorganization is affected through time, eventually producing a form or structure that is qualitatively different from the ancestral form".

George Ledyard Stebbins Jr. was an American botanist and geneticist who is widely regarded as one of the leading evolutionary biologists of the 20th century. Stebbins received his Ph.D. in botany from Harvard University in 1931. He went on to the University of California, Berkeley, where his work with E. B. Babcock on the genetic evolution of plant species, and his association with a group of evolutionary biologists known as the Bay Area Biosystematists, led him to develop a comprehensive synthesis of plant evolution incorporating genetics.

Mutationism is one of several alternatives to evolution by natural selection that have existed both before and after the publication of Charles Darwin's 1859 book On the Origin of Species. In the theory, mutation was the source of novelty, creating new forms and new species, potentially instantaneously, in sudden jumps. This was envisaged as driving evolution, which was thought to be limited by the supply of mutations.

Peter J. Bowler is a historian of biology who has written extensively on the history of evolutionary thought, the history of the environmental sciences, and on the history of genetics. His 1984 book, Evolution: The History of an Idea is a standard textbook on the history of evolution; a 25th anniversary edition came in 2009. His 1983 book The Eclipse of Darwinism: Anti-Darwinian Evolution Theories in the Decades Around 1900 describes the scientific predominance of other evolutionary theories which led many to minimise the significance of natural selection, in the first part of the twentieth century before genetics was reconciled with natural selection in the modern synthesis.

Evolution: The Modern Synthesis, a popularising 1942 book by Julian Huxley, set out his vision of the modern synthesis of evolutionary biology of the mid-20th century. It was enthusiastically reviewed in academic biology journals.

Julian Huxley used the phrase "the eclipse of Darwinism" to describe the state of affairs prior to what he called the "modern synthesis". During the "eclipse", evolution was widely accepted in scientific circles but relatively few biologists believed that natural selection was its primary mechanism. Historians of science such as Peter J. Bowler have used the same phrase as a label for the period within the history of evolutionary thought from the 1880s to around 1920, when alternatives to natural selection were developed and explored—as many biologists considered natural selection to have been a wrong guess on Charles Darwin's part, or at least to be of relatively minor importance.

Mongoloid is an obsolete racial grouping of various peoples indigenous to large parts of Asia, the Americas, and some regions in Europe and Oceania. The term is derived from a now-disproven theory of biological race. In the past, other terms such as "Mongolian race", "yellow", "Asiatic" and "Oriental" have been used as synonyms.

Evolutionary thought, the recognition that species change over time and the perceived understanding of how such processes work, has roots in antiquity—in the ideas of the ancient Greeks, Romans, Chinese, Church Fathers as well as in medieval Islamic science. With the beginnings of modern biological taxonomy in the late 17th century, two opposed ideas influenced Western biological thinking: essentialism, the belief that every species has essential characteristics that are unalterable, a concept which had developed from medieval Aristotelian metaphysics, and that fit well with natural theology; and the development of the new anti-Aristotelian approach to modern science: as the Enlightenment progressed, evolutionary cosmology and the mechanical philosophy spread from the physical sciences to natural history. Naturalists began to focus on the variability of species; the emergence of palaeontology with the concept of extinction further undermined static views of nature. In the early 19th century prior to Darwinism, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829) proposed his theory of the transmutation of species, the first fully formed theory of evolution.

Although biological evolution has been vocally opposed by some religious groups, many other groups accept the scientific position, sometimes with additions to allow for theological considerations. The positions of such groups are described by terms including "theistic evolution", "theistic evolutionism" or "evolutionary creation". Of all the religious groups included on the chart, Buddhists are the most accepting of evolution. Theistic evolutionists believe that there is a God, that God is the creator of the material universe and all life within, and that biological evolution is a natural process within that creation. Evolution, according to this view, is simply a tool that God employed to develop human life. According to the American Scientific Affiliation, a Christian organization of scientists:

A theory of theistic evolution (TE) — also called evolutionary creation — proposes that God's method of creation was to cleverly design a universe in which everything would naturally evolve. Usually the "evolution" in "theistic evolution" means Total Evolution — astronomical evolution and geological evolution plus chemical evolution and biological evolution — but it can refer only to biological evolution.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to evolution:

Cultural evolution is an evolutionary theory of social change. It follows from the definition of culture as "information capable of affecting individuals' behavior that they acquire from other members of their species through teaching, imitation and other forms of social transmission". Cultural evolution is the change of this information over time.

Monad to Man: the concept of progress in evolutionary biology is a 1996 book about the longstanding idea that evolution is progressive by the philosopher of biology Michael Ruse. It analyses the connection between ideas of progress in culture generally and its application in evolutionary biology.