A gill is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are kept moist. The microscopic structure of a gill presents a large surface area to the external environment. Branchia is the zoologists' name for gills.

Aquatic respiration is the process whereby an aquatic organism exchanges respiratory gases with water, obtaining oxygen from oxygen dissolved in water and excreting carbon dioxide and some other metabolic waste products into the water.

Aquatic insects or water insects live some portion of their life cycle in the water. They feed in the same ways as other insects. Some diving insects, such as predatory diving beetles, can hunt for food underwater where land-living insects cannot compete.

The American water shrew or northern water shrew is a shrew found in the nearctic faunal region located throughout the mountain ranges of the northern United States and in Canada and Alaska. The organism resides in semi-aquatic habitats, and is known for being the smallest mammalian diver.

Cybaeidae is a family of spiders first described by Nathan Banks in 1892. The diving bell spider or water spider Argyroneta aquatica was previously included in this family, but is now in the family Dictynidae.

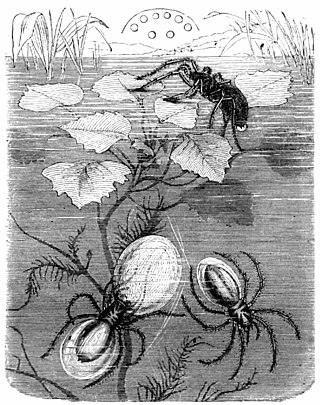

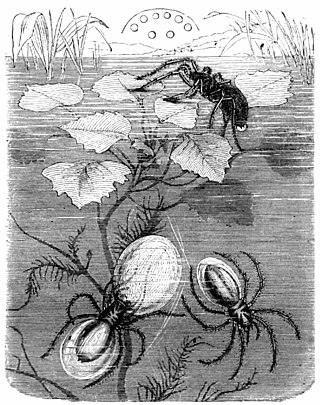

The raft spider, scientific name Dolomedes fimbriatus, is a large semi-aquatic spider of the family Pisauridae found throughout north-western and central Europe. It is one of only two species of the genus Dolomedes found in Europe, the other being the slightly larger Dolomedesplantarius which is endangered in the UK.

Misumena vatia is a species of crab spider with a holarctic distribution. In North America, it is called the goldenrod crab spider or flower (crab) spider, as it is commonly found hunting in goldenrod sprays and milkweed plants. They are called crab spiders because of their unique ability to walk sideways as well as forwards and backwards. Both males and females of this species progress through several molts before reaching their adult sizes, though females must molt more to reach their larger size. Females can grow up to 10 mm (0.39 in) while males are quite small, reaching 5 mm (0.20 in) at most. Misumena vatia are usually yellow or white or a pattern of these two colors. They may also present with pale green or pink instead of yellow, again, in a pattern with white. They have the ability to change between these colors based on their surroundings through the molting process. They have a complex visual system, with eight eyes, that they rely on for prey capture and for their color-changing abilities. Sometimes, if Misumena vatia consumes colored prey, the spider itself will take on that color.

Spider behavior refers to the range of behaviors and activities performed by spiders. Spiders are air-breathing arthropods that have eight legs and chelicerae with fangs that inject venom. They are the largest order of arachnids and rank seventh in total species diversity among all other groups of organisms which is reflected in their large diversity of behavior.

The anatomy of spiders includes many characteristics shared with other arachnids. These characteristics include bodies divided into two tagmata, eight jointed legs, no wings or antennae, the presence of chelicerae and pedipalps, simple eyes, and an exoskeleton, which is periodically shed.

Spider cannibalism is the act of a spider consuming all or part of another individual of the same species as food. It is most commonly seen as an example of female sexual cannibalism where a female spider kills and eats a male before, during, or after copulation. Cases of non-sexual cannibalism or male cannibalism of females both occur but are notably rare.

Saltonia is a monotypic genus of North American cribellate araneomorph spiders in the family Dictynidae containing the single species, Saltonia incerta. It was first described by R. V. Chamberlin & Wilton Ivie in 1942, and has only been found in United States. Originally placed with the funnel weavers, it was moved to the Dictynidae in 1967.

Ancylometes is a genus of Central and South American semiaquatic wandering spiders first described by Philipp Bertkau in 1880. Originally placed with the nursery web spiders, it was moved to the Ctenidae in 1967. The genus name is derived in part from Ancient Greek "ἀγκύλος", meaning "crooked, bent".

Notonecta glauca is a species of aquatic insect, and a type of backswimmer. This species is found in large parts of Europe, North Africa, and east through Asia to Siberia and China. In much of its range it is the most common backswimmer species. It is also the most widespread and abundant of the four British backswimmers. Notonecta glauca are Hemiptera predators, that are approximately 13–16 mm in length. Females have a larger body size compared to males. These water insects swim and rest on their back and are found under the water surface. Notonecta glauca supports itself under the water surface by using their front legs and mid legs and the back end of its abdomen and rest them on the water surface; They are able to stay under the water surface by water tension, also known as the air-water interface. They use the hind legs as oars; these legs are fringed with hair and, when at rest, are extended laterally like a pair of sculls in a boat. Notonecta glauca will either wait for its prey to pass by or will swim and actively hunt its prey. When the weather is warm, usually in the late summer and autumn, they will fly between ponds. Notonecta glauca reproduce in the spring.

The Japanese water spider is a subspecies of the water spider. In Japanese it is called the mizugumo. The Japanese water spider is almost exactly like its European cousin. The only distinction between the two is that the Japanese water spider has larger genitalia. Like its cousin, the Japanese water spider lives under water by constructing diving bells, underwater spheres which contain oxygen, which they live in.

The six-spotted fishing spider is an arachnid from the nursery web spider family Pisauridae. This species is from the genus Dolomedes, or the fishing spiders. Found in wetland habitats throughout North America, these spiders are usually seen scampering along the surface of ponds and other bodies of water. They are also referred to as dock spiders because they can sometimes be witnessed quickly vanishing through the cracks of boat docks. D. triton gets its scientific name from the Greek mythological god Triton, who is the messenger of the big sea and the son of Poseidon.

Spiders are air-breathing arthropods that have eight limbs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and rank seventh in total species diversity among all orders of organisms. Spiders are found worldwide on every continent except for Antarctica, and have become established in nearly every land habitat. As of November 2023, 51,673 spider species in 136 families have been recorded by taxonomists. However, there has been debate among scientists about how families should be classified, with over 20 different classifications proposed since 1900.

Desis marina, the intertidal spider, is a spider species found in New Zealand, New Caledonia, and the Chatham Islands.

Desis bobmarleyi is an underwater spider species found in the shores of north eastern Queensland, Australia. It is known to build air chambers from silk. D. bobmarleyi is named in honour of the Jamaican singer-songwriter Bob Marley. As an intertidal species the name was inspired by Marley's song "High Tide or Low Tide". In April 2018 the World Register of Marine Species named it one of the top 10 most remarkable species discovered in 2017. The spider is an araneomorph. D. bobmarleyi is a recent discovery, which is important to note when examining its data. Additionally, because it is part of the genus Desis, it is considered a fully aquatic animal which is interesting because of its evolutionary history. The trnL2 and trnN genes, which are seen in marine spiders that are a part of the genus, must have experienced some kind of rearrangement that allowed for the development of its current traits. The long hairs on its legs and abdomen trap an air bubble which allows it to breathe while submerged.

Anolis aquaticus, commonly known as the water anole, is a semi-aquatic species of anole, a lizard in the family Dactyloidae, native to southwestern Costa Rica and far southwestern Panama. The species demonstrates adaptations that allows it to spend periods of time underwater up to approximately a quarter of an hour, forming an air bubble which clings to its head and serves to recycle the animal's air supply while it spends time beneath the surface. Although highly unusual, similar adaptions and behavior are found in other species of semi-aquatic anoles.

Dolomedes dondalei is a species of large fishing spider endemic to the main islands of New Zealand. It is a nocturnal hunter, feeling the water surface for vibrations, and catches insects and even small fishes – the only New Zealand Dolomedes species able to do so.