The Huilliche, Huiliche or Huilliche-Mapuche are the southern partiality of the Mapuche macroethnic group in Chile and Argentina. Located in the Zona Sur, they inhabit both Futahuillimapu and, as the Cunco or Veliche subgroup, the northern half of Chiloé Island. The Huilliche are the principal indigenous people of those regions. According to Ricardo E. Latcham the term Huilliche started to be used in Spanish after the second founding of Valdivia in 1645, adopting the usage of the Mapuches of Araucanía for the southern Mapuche tribes. Huilliche means 'southerners' A genetic study showed significant affinities between Huilliches and indigenous peoples east of the Andes, which suggests but does not prove a partial origin in present-day Argentina.

This is a timeline of Chilean history, comprising important legal and territorial changes and political events in Chile and its predecessor states. To read about the background to these events, see History of Chile. See also the list of governors and presidents of Chile.

Osorno is a city and commune in southern Chile and capital of Osorno Province in the Los Lagos Region. It had a population of 145,475, as of the 2002 census. It is located 945 kilometres (587 mi) south of the national capital of Santiago, 105 kilometres (65 mi) north of the regional capital of Puerto Montt and 260 kilometres (160 mi) west of the Argentine city of San Carlos de Bariloche, connected via International Route 215 through the Cardenal Antonio Samoré Pass. It is a gateway for land access to the far south regions of Aysén and Magallanes, which would otherwise be accessible only by sea or air from the rest of the country.

The Fort System of Valdivia is a series of Spanish colonial fortifications at Corral Bay, Valdivia and Cruces River established to protect the city of Valdivia, in southern Chile. During the period of Spanish rule (1645–1820), it was one of the biggest systems of fortification in the Americas. It was also a major supply source for Spanish ships that crossed the Strait of Magellan.

The Destruction of the Seven Cities is a term used in Chilean historiography to refer to the destruction or abandonment of seven major Spanish outposts in southern Chile around 1600, caused by the Mapuche and Huilliche uprising of 1598. The Destruction of the Seven Cities, in traditional historiography, marks the end of the Conquest period and the beginning of the proper colonial period.

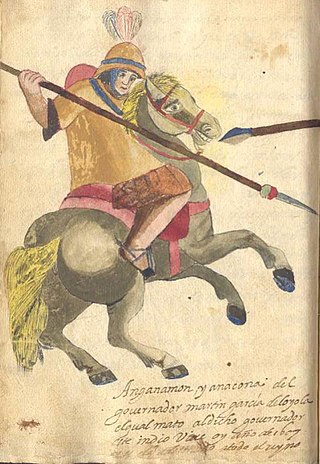

The Conquest of Chile is a period in Chilean historiography that starts with the arrival of Pedro de Valdivia to Chile in 1541 and ends with the death of Martín García Óñez de Loyola in the Battle of Curalaba in 1598, and the destruction of the Seven Cities in 1598–1604 in the Araucanía region.

Cuncos, Juncos or Cunches is a poorly known subgroup of Huilliche people native to coastal areas of southern Chile and the nearby inland. Mostly a historic term, Cuncos are chiefly known for their long-running conflict with the Spanish during the colonial era of Chilean history.

Valdivia is one of the few cities in southern Chile with a more less continuous and well documented history from its foundation in the 16th century onwards.

In Chilean historiography, Colonial Chile is the period from 1600 to 1810, beginning with the Destruction of the Seven Cities and ending with the onset of the Chilean War of Independence. During this time, the Chilean heartland was ruled by Captaincy General of Chile. The period was characterized by a lengthy conflict between Spaniards and native Mapuches known as the Arauco War. Colonial society was divided in distinct groups including Peninsulars, Criollos, Mestizos, Indians and Black people.

The history of Chiloé, an archipelago in Chile's south, has been marked by its geographic and political isolation. The archipelago has been described by Renato Cárdenas, historian at the Chilean National Library, as “a distinct enclave, linked more to the sea than the continent, a fragile society with a strong sense of solidarity and a deep territorial attachment.”

As an archaeological culture, the Mapuche people of southern Chile and Argentina have a long history which dates back to 600–500 BC. The Mapuche society underwent great transformations after Spanish contact in the mid–16th century. These changes included the adoption of Old World crops and animals and the onset of a rich Spanish–Mapuche trade in La Frontera and Valdivia. Despite these contacts Mapuche were never completely subjugated by the Spanish Empire. Between the 18th and 19th century Mapuche culture and people spread eastwards into the Pampas and the Patagonian plains. This vast new territory allowed Mapuche groups to control a substantial part of the salt and cattle trade in the Southern Cone.

In Colonial times the Spanish Empire diverted significant resources to fortify the Chilean coast as consequence of Dutch and English raids. The Spanish attempts to block the entrance of foreign ships to the eastern Pacific proved fruitless due to the failure to settle the Strait of Magellan and the discovery of the Drake Passage. As result of this the Spanish settlement at Chiloé Archipelago became a centre from where the west coast of Patagonia was protected from foreign powers. In face of the international wars that involved the Spanish Empire in the second half of the 18th century the Crown was unable to directly protect peripheral colonies like Chile leading to local government and militias assuming the increased responsibilities.

In Colonial times the Spanish Empire diverted significant resources to fortify the Chilean coast as a consequence of Dutch and English raids. During the 16th century the Spanish strategy was to complement the fortification work in its Caribbean ports with forts in the Strait of Magellan. As attempts at settling and fortifying the Strait of Magellan were abandoned the Spanish began to fortify the Captaincy General of Chile and other parts of the west coast of the Americas. The coastal fortifications and defense system was at its peak in the mid-18th century.

The Governorate of Chiloé was political and military subdivision of the Spanish Empire that existed, with a 1784–1789 interregnum,from 1567 to 1848. The Governorate of Chiloé depended on the Captaincy General of Chile until the late 18th century when it was made dependent directly on the Viceroyalty of Peru. The administrative change was done simultaneously as the capital of the archipelago was moved from Castro to Ancud in 1768. The last Royal Governor of Chiloé, Antonio de Quintanilla, depended directly on the central government in Madrid.

Juan Manqueante was a Mapuche cacique from Mariquina in the mid-17th century. While he is a historical figure there are many legends and tales associated to him. In local lore Manqueante is considered him the most notable person born in the lands of Mariquina. There is a street in San José named after him.

The battle of Río Bueno was fought in 1654 between the Spanish Army of Arauco and indigenous Cuncos and Huilliches of Fütawillimapu in southern Chile. The battle took place against a background of a long-running enmity between the Cuncos and Spanish, dating back to the destruction of Osorno in 1603. More immediate causes were the killing of Spanish shipwreck survivors and looting of the cargo by Cuncos, which led to Spanish desires for a punishment, combined with the prospects of lucrative slave raiding.

The Mapuche uprising of 1655 was a series of coordinated Mapuche attacks against Spanish settlements and forts in colonial Chile. It was the worst military crisis in Chile in decades, and contemporaries even considered the possibility of a civil war among the Spanish. The uprising marks the beginning of a ten-year period of warfare between the Spanish and the Mapuche.

The Antonio de Vea expedition of 1675–1676 was a Spanish naval expedition to the fjords and channels of Patagonia aimed to find whether rival colonial powers—specifically, the English—were active in the region. While this was not the first Spanish expedition to the region, it was the largest up to then, involving 256 men, one ocean-going ship, two long boats and nine dalcas. The expedition dispelled suspicion about English bases in Patagonia. Spanish authorities' knowledge of western Patagonia was greatly improved by the expedition, yet Spanish interest in the area waned thereafter until the 1740s.

The Huilliche uprising of 1792 was an indigenous uprising against the Spanish penetration into Futahuillimapu, territory in southern Chile that had been de facto free of Spanish rule since 1602. The first part of the conflict was a series of Huilliche attacks on Spanish settlers and the mission in the frontier next to Bueno River. Following this a militia in charge of Tomás de Figueroa departed from Valdivia ravaging Huilliche territory in a quest to subdue anti-Spanish elements in Futahuillimapu.

The 1651 wreckage of San José and the subsequent killings and looting carried out by indigenous Cuncos was a defining event in Colonial Chile that contributed to Spanish-Cunco tensions that led to the Battle of Río Bueno and the Mapuche uprising of 1655.