Vorticism was a London-based modernist art movement formed in 1914 by the writer and artist Wyndham Lewis. The movement was partially inspired by Cubism and was introduced to the public by means of the publication of the Vorticist manifesto in Blast magazine. Familiar forms of representational art were rejected in favour of a geometric style that tended towards a hard-edged abstraction. Lewis proved unable to harness the talents of his disparate group of avant-garde artists; however, for a brief period Vorticism proved to be an exciting intervention and an artistic riposte to Marinetti's Futurism and the post-impressionism of Roger Fry's Omega Workshops.

Futurism was an artistic and social movement that originated in Italy, and to a lesser extent in other countries, in the early 20th century. It emphasized dynamism, speed, technology, youth, violence, and objects such as the car, the airplane, and the industrial city. Its key figures included the Italians Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Fortunato Depero, Gino Severini, Giacomo Balla, and Luigi Russolo. Italian Futurism glorified modernity and according to its doctrine, aimed to liberate Italy from the weight of its past. Important Futurist works included Marinetti's 1909 Manifesto of Futurism, Boccioni's 1913 sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, Balla's 1913–1914 painting Abstract Speed + Sound, and Russolo's The Art of Noises (1913).

Umberto Boccioni was an influential Italian painter and sculptor. He helped shape the revolutionary aesthetic of the Futurism movement as one of its principal figures. Despite his short life, his approach to the dynamism of form and the deconstruction of solid mass guided artists long after his death. His works are held by many public art museums, and in 1988 the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City organized a major retrospective of 100 pieces.

Events from the year 1912 in art.

Giacomo Balla was an Italian painter, art teacher and poet best known as a key proponent of Futurism. In his paintings, he depicted light, movement and speed. He was concerned with expressing movement in his works, but unlike other leading futurists he was not interested in machines or violence with his works tending towards the witty and whimsical.

Gino Severini was an Italian painter and a leading member of the Futurist movement. For much of his life he divided his time between Paris and Rome. He was associated with neo-classicism and the "return to order" in the decade after the First World War. During his career he worked in a variety of media, including mosaic and fresco. He showed his work at major exhibitions, including the Rome Quadrennial, and won art prizes from major institutions.

Gerardo Dottori was an Italian Futurist painter. He signed the Futurist Manifesto of Aeropainting in 1929. He was associated with the city of Perugia most of his life, living in Milan for six months as a student and in Rome from 1926-39. Dottori's' principal output was the representation of landscapes and visions of Umbria, mostly viewed from a great height. Among the most famous of these are Umbrian Spring and Fire in the City, both from the early 1920s; this last one is now housed in the Museo civico di Palazzo della Penna in Perugia, with many of Dottori's other works. His work was part of the art competitions at the 1932 Summer Olympics and the 1936 Summer Olympics.

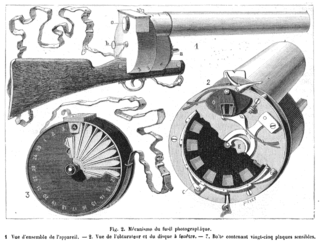

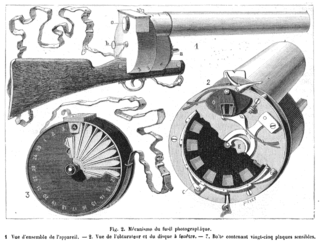

The chronophotographic gun is one of the ancestors of the movie camera. It was invented in 1882 by Étienne-Jules Marey, a French scientist and chronophotographer. It could shoot 12 images per second and it was the first invention to capture moving images on the same chronomatographic plate using a metal shutter.

Aeropittura (Aeropainting) was a major expression of the second generation of Italian Futurism, from 1929 through the early 1940s. The technology and excitement of flight, directly experienced by most aeropainters, offered aeroplanes and aerial landscape as new subject matter.

Anson Conger Goodyear was an American manufacturer, businessman, author, and philanthropist and member of the Goodyear family. He is best known as one of the founding members and first president of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Benedetta Cappa was an Italian futurist artist who has had retrospectives at the Walker Art Center and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Her work fits within the second phase of Italian Futurism.

Girl Running on a Balcony is a 1912 painting by Giacomo Balla, one of the forerunners of the Italian movement called Futurism. The piece indicates the artist's growing interests in creative nuances which would later formally be realized as part of the Futurist movement. The artist was heavily influenced by northern Italians' use of Divisionism and the French's better-known pointillism. Created with oil on canvas just on the brink of World War I, the Futurist movement is embodied by a dark optimism for a future of speed, turbulence, chaos, and new beginnings. Most of Giacaomo Balla's pieces allude to the wonder of dynamic movement, and this painting is no exception. The oil painting is now in the Museo del Novecento, in Milan.

Dynamism of a Cyclist is a 1913 oil painting by Italian Futurist artist Umberto Boccioni (1882–1916) that demonstrates the Futurist fascination with speed, modern methods of transport, and the depiction of the dynamic sensation of movement.

The Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto (1910) by Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916) was the first exposition of the theoretical underpinnings of Italian Futurist painting.

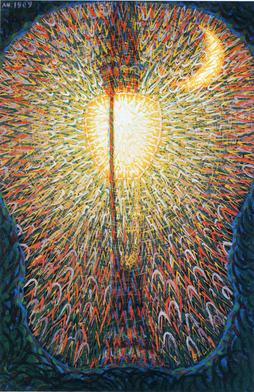

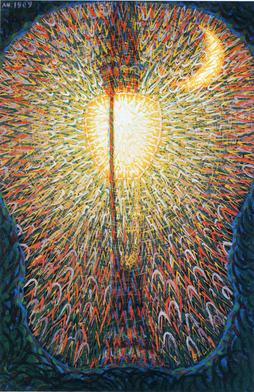

Street Light (also known as The Street Light: Study of Light and Street Lamp (Suffering of a Street Lamp)) (Italian: Lampada ad arco) is a painting by Italian Futurist painter Giacomo Balla, dated 1909, depicting an electric street lamp casting a glow that outshines the crescent moon. The painting was inspired by streetlights at the Piazza Termini in Rome.

Abstract Speed + Sound is a painting by Italian Futurist painter Giacomo Balla, one of several studies of motion created by the artist in 1913–14.

Mercury Passing Before the Sun is the title of a series of paintings by Italian Futurist painter Giacomo Balla, depicting the November 17, 1914, transit of Mercury across the face of the Sun.

The Hand of the Violinist (The Rhythms of the Bow) is a 1912 painting by Italian Futurist Giacomo Balla, depicting a musician's hand and the neck of a violin "made to look like it's vibrating through space"—blurred and duplicated to suggest the motion of frenetic playing. The painting, representative of Futurism's first wave, exhibits techniques of Divisionism.

Růžena Zátková, also called Rougina Zatkova, was a painter and sculptor who has been regarded as the "only authentic Czech futurist." As a result of her Bohemian heritage and her decade-long residency in Rome, Růžena Zátková became an important artistic link between Russian and Italian Futurism. Zátková is considered one of the pioneers of kinetic art.

Dynamism of a Car is a 1913 Futurist painting by Italian artist Luigi Russolo. It is currently held in the Musée National d'Art Moderne.