Futurism was an artistic and social movement that originated in Italy, and to a lesser extent in other countries, in the early 20th century. It emphasized dynamism, speed, technology, youth, violence, and objects such as the car, the airplane, and the industrial city. Its key figures included the Italians Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Fortunato Depero, Gino Severini, Giacomo Balla, and Luigi Russolo. Italian Futurism glorified modernity and according to its doctrine, aimed to liberate Italy from the weight of its past. Important Futurist works included Marinetti's 1909 Manifesto of Futurism, Boccioni's 1913 sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, Balla's 1913–1914 painting Abstract Speed + Sound, and Russolo's The Art of Noises (1913).

Umberto Boccioni was an influential Italian painter and sculptor. He helped shape the revolutionary aesthetic of the Futurism movement as one of its principal figures. Despite his short life, his approach to the dynamism of form and the deconstruction of solid mass guided artists long after his death. His works are held by many public art museums, and in 1988 the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City organized a major retrospective of 100 pieces.

Giacomo Balla was an Italian painter, art teacher and poet best known as a key proponent of Futurism. In his paintings, he depicted light, movement and speed. He was concerned with expressing movement in his works, but unlike other leading futurists he was not interested in machines or violence with his works tending towards the witty and whimsical.

Gino Severini was an Italian painter and a leading member of the Futurist movement. For much of his life he divided his time between Paris and Rome. He was associated with neo-classicism and the "return to order" in the decade after the First World War. During his career he worked in a variety of media, including mosaic and fresco. He showed his work at major exhibitions, including the Rome Quadrennial, and won art prizes from major institutions.

Italian futurist cinema was the oldest movement of European avant-garde cinema. Italian futurism, an artistic and social movement, impacted the Italian film industry from 1916 to 1919. It influenced Russian Futurist cinema and German Expressionist cinema. Its cultural importance was considerable and influenced all subsequent avant-gardes, as well as some authors of narrative cinema; its echo expands to the dreamlike visions of some films by Alfred Hitchcock.

Zang Tumb Tumb is a sound poem and concrete poem written by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, an Italian futurist. It appeared in excerpts in journals between 1912 and 1914, when it was published as an artist's book in Milan. It is an account of the Battle of Adrianople, which he witnessed as a reporter for L'Intransigeant. The poem uses Parole in libertà and other poetic impressions of the events of the battle, including the sounds of gunfire and explosions. The work is now seen as a seminal work of modernist art, and an enormous influence on the emerging culture of European avant-garde print.

"[The] masterpiece of Words-in-freedom and of Marinetti’s literary career was the novel Zang Tumb Tuuum... the story of the siege by the Bulgarians of Turkish Adrianople in the Balkan War, which Marinetti had witnessed as a war reporter. The dynamic rhythms and onomatopoetic possibilities that the new form offered were made even more effective through the revolutionary use of different typefaces, forms and graphic arrangements and sizes that became a distinctive part of Futurism. In Zang Tumb Tuuum; they are used to express an extraordinary range of different moods and speeds, quite apart from the noise and chaos of battle.... Audiences in London, Berlin and Rome alike were bowled over by the tongue-twisting vitality with which Marinetti declaimed Zang Tumb Tuuum. As an extended sound poem it stands as one of the monuments of experimental literature, its telegraphic barrage of nouns, colours, exclamations and directions pouring out in the screeching of trains, the rat-a-tat-tat of gunfire, and the clatter of telegraphic messages." — Caroline Tisdall and Angelo Bozzola

Cubo-Futurism or Kubo-Futurizm was an art movement, developed within Russian Futurism, that arose in early 20th century Russian Empire, defined by its amalgamation of the artistic elements found in Italian Futurism and French Analytical Cubism. Cubo-Futurism was the main school of painting and sculpture practiced by the Russian Futurists. In 1913, the term "Cubo-Futurism" first came to describe works from members of the poetry group "Hylaeans", as they moved away from poetic Symbolism towards Futurism and zaum, the experimental "visual and sound poetry of Kruchenykh and Khlebninkov". Later in the same year the concept and style of "Cubo-Futurism" became synonymous with the works of artists within Ukrainian and Russian post-revolutionary avant-garde circles as they interrogated non-representational art through the fragmentation and displacement of traditional forms, lines, viewpoints, colours, and textures within their pieces. The impact of Cubo-Futurism was then felt within performance art societies, with Cubo-Futurist painters and poets collaborating on theatre, cinema, and ballet pieces that aimed to break theatre conventions through the use of nonsensical zaum poetry, emphasis on improvisation, and the encouragement of audience participation.

Futurist architecture is an early-20th century form of architecture born in Italy, characterized by long dynamic lines, suggesting speed, motion, urgency and lyricism: it was a part of Futurism, an artistic movement founded by the poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who produced its first manifesto, the Manifesto of Futurism, in 1909. The movement attracted not only poets, musicians, and artists but also a number of architects. A cult of the Machine Age and even a glorification of war and violence were among the themes of the Futurists - several prominent futurists were killed after volunteering to fight in World War I. The latter group included the architect Antonio Sant'Elia, who, though building little, translated the futurist vision into an urban form.

Divisionism, also called chromoluminarism, is the characteristic style in Neo-Impressionist painting defined by the separation of colors into individual dots or patches that interact optically.

Italian Contemporary art refers to painting and sculpture in Italy from the early 20th century onwards.

The Street Enters the House is an 1912 oil on canvas painting by Italian artist Umberto Boccioni. Painted in the Futurist style, the work centres on a woman on a balcony in front of a busy street, with the sounds of the activity below portrayed as a riot of shapes and colours.

Development of a Bottle in Space is a bronze futurist sculpture by Umberto Boccioni. Initially a sketch in Boccioni’s "Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture"," the design was later cast into bronze by Boccioni himself in the year 1913. Consistent with many of themes in Boccioni’s manifesto, the work of art highlights the artist’s first successful attempt at creating a sculpture that both molds and encloses space within itself.

Arnaldo Ginna, also known as Arnaldo Ginanni Corradini, was an Italian painter, sculptor and filmmaker. He was born in Ravenna, 7 May 1890; he died in Rome, 26 September 1982.

Benedetta Cappa was an Italian futurist artist who has had retrospectives at the Walker Art Center and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Her work fits within the second phase of Italian Futurism.

Dynamism of a Cyclist is a 1913 oil painting by Italian Futurist artist Umberto Boccioni (1882–1916) that demonstrates the Futurist fascination with speed, modern methods of transport, and the depiction of the dynamic sensation of movement.

The Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto (1910) by Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916) was the first exposition of the theoretical underpinnings of Italian Futurist painting.

Three Women is a painting by Italian artist Umberto Boccioni, executed between 1909 and 1910. This painting is oil on canvas painted in the style of divisionism. Divisionism refers to the actual division of colors by creating separated brush strokes as opposed to smooth, solid lines. The painting contains three figures, one being Boccioni's mother Cecilia on the left, another being his sister, Amelia on the right, and the third being Ines, his lover, in the center.

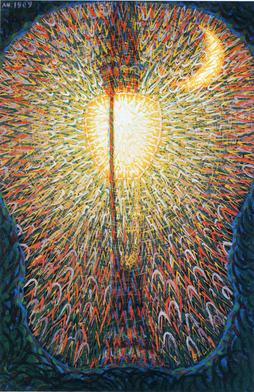

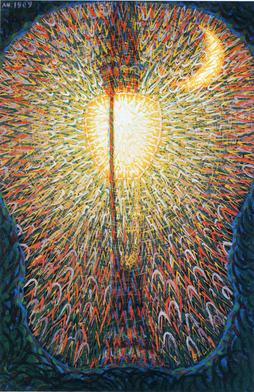

Street Light (also known as The Street Light: Study of Light and Street Lamp (Suffering of a Street Lamp)) (Italian: Lampada ad arco) is a painting by Italian Futurist painter Giacomo Balla, dated 1909, depicting an electric street lamp casting a glow that outshines the crescent moon. The painting was inspired by streetlights at the Piazza Termini in Rome.

Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, sometimes called Dog on a Leash or Leash in Motion, is a 1912 oil painting by Italian Futurist painter Giacomo Balla. It was influenced by the artist's fascination with chronophotographic studies of animals in motion. It is considered one of his best-known works, and one of the most important works in Futurism, though it received mixed critical reviews. The painting has been in the collection of the Albright–Knox Art Gallery since 1984.

Růžena Zátková, also called Rougina Zatkova, was a painter and sculptor who has been regarded as the "only authentic Czech futurist." As a result of her Bohemian heritage and her decade-long residency in Rome, Růžena Zátková became an important artistic link between Russian and Italian Futurism. Zátková is considered one of the pioneers of kinetic art.