In particle physics, the Dirac equation is a relativistic wave equation derived by British physicist Paul Dirac in 1928. In its free form, or including electromagnetic interactions, it describes all spin-1⁄2 massive particles, called "Dirac particles", such as electrons and quarks for which parity is a symmetry. It is consistent with both the principles of quantum mechanics and the theory of special relativity, and was the first theory to account fully for special relativity in the context of quantum mechanics. It was validated by accounting for the fine structure of the hydrogen spectrum in a completely rigorous way.

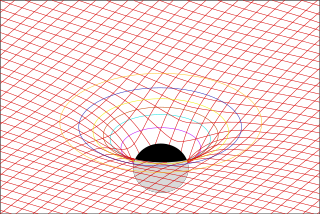

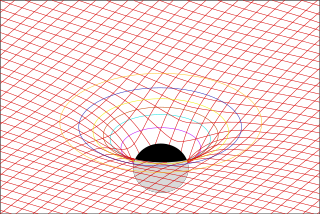

The stress–energy tensor, sometimes called the stress–energy–momentum tensor or the energy–momentum tensor, is a tensor physical quantity that describes the density and flux of energy and momentum in spacetime, generalizing the stress tensor of Newtonian physics. It is an attribute of matter, radiation, and non-gravitational force fields. This density and flux of energy and momentum are the sources of the gravitational field in the Einstein field equations of general relativity, just as mass density is the source of such a field in Newtonian gravity.

The Klein–Gordon equation is a relativistic wave equation, related to the Schrödinger equation. It is second-order in space and time and manifestly Lorentz-covariant. It is a differential equation version of the relativistic energy–momentum relation .

In special relativity, a four-vector is an object with four components, which transform in a specific way under Lorentz transformations. Specifically, a four-vector is an element of a four-dimensional vector space considered as a representation space of the standard representation of the Lorentz group, the representation. It differs from a Euclidean vector in how its magnitude is determined. The transformations that preserve this magnitude are the Lorentz transformations, which include spatial rotations and boosts.

An electromagnetic four-potential is a relativistic vector function from which the electromagnetic field can be derived. It combines both an electric scalar potential and a magnetic vector potential into a single four-vector.

In differential geometry, the four-gradient is the four-vector analogue of the gradient from vector calculus.

In theoretical physics, massive gravity is a theory of gravity that modifies general relativity by endowing the graviton with a nonzero mass. In the classical theory, this means that gravitational waves obey a massive wave equation and hence travel at speeds below the speed of light.

A theoretical motivation for general relativity, including the motivation for the geodesic equation and the Einstein field equation, can be obtained from special relativity by examining the dynamics of particles in circular orbits about the Earth. A key advantage in examining circular orbits is that it is possible to know the solution of the Einstein Field Equation a priori. This provides a means to inform and verify the formalism.

In relativistic physics, the electromagnetic stress–energy tensor is the contribution to the stress–energy tensor due to the electromagnetic field. The stress–energy tensor describes the flow of energy and momentum in spacetime. The electromagnetic stress–energy tensor contains the negative of the classical Maxwell stress tensor that governs the electromagnetic interactions.

The covariant formulation of classical electromagnetism refers to ways of writing the laws of classical electromagnetism in a form that is manifestly invariant under Lorentz transformations, in the formalism of special relativity using rectilinear inertial coordinate systems. These expressions both make it simple to prove that the laws of classical electromagnetism take the same form in any inertial coordinate system, and also provide a way to translate the fields and forces from one frame to another. However, this is not as general as Maxwell's equations in curved spacetime or non-rectilinear coordinate systems.

In physics, Maxwell's equations in curved spacetime govern the dynamics of the electromagnetic field in curved spacetime or where one uses an arbitrary coordinate system. These equations can be viewed as a generalization of the vacuum Maxwell's equations which are normally formulated in the local coordinates of flat spacetime. But because general relativity dictates that the presence of electromagnetic fields induce curvature in spacetime, Maxwell's equations in flat spacetime should be viewed as a convenient approximation.

There are various mathematical descriptions of the electromagnetic field that are used in the study of electromagnetism, one of the four fundamental interactions of nature. In this article, several approaches are discussed, although the equations are in terms of electric and magnetic fields, potentials, and charges with currents, generally speaking.

In mathematical physics, spacetime algebra (STA) is the application of Clifford algebra Cl1,3(R), or equivalently the geometric algebra G(M4) to physics. Spacetime algebra provides a "unified, coordinate-free formulation for all of relativistic physics, including the Dirac equation, Maxwell equation and General Relativity" and "reduces the mathematical divide between classical, quantum and relativistic physics."

The theory of special relativity plays an important role in the modern theory of classical electromagnetism. It gives formulas for how electromagnetic objects, in particular the electric and magnetic fields, are altered under a Lorentz transformation from one inertial frame of reference to another. It sheds light on the relationship between electricity and magnetism, showing that frame of reference determines if an observation follows electric or magnetic laws. It motivates a compact and convenient notation for the laws of electromagnetism, namely the "manifestly covariant" tensor form.

In theoretical physics, relativistic Lagrangian mechanics is Lagrangian mechanics applied in the context of special relativity and general relativity.

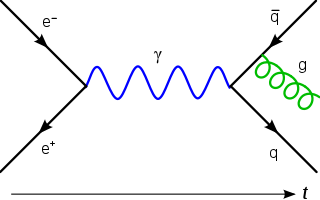

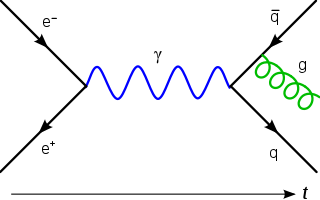

In theoretical particle physics, the gluon field strength tensor is a second order tensor field characterizing the gluon interaction between quarks.

The optical metric was defined by German theoretical physicist Walter Gordon in 1923 to study the geometrical optics in curved space-time filled with moving dielectric materials.

Lagrangian field theory is a formalism in classical field theory. It is the field-theoretic analogue of Lagrangian mechanics. Lagrangian mechanics is used to analyze the motion of a system of discrete particles each with a finite number of degrees of freedom. Lagrangian field theory applies to continua and fields, which have an infinite number of degrees of freedom.

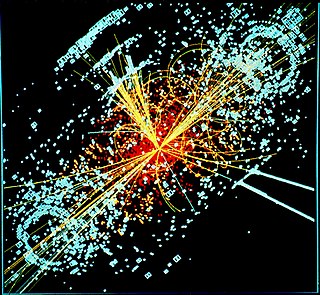

Attempts have been made to describe gauge theories in terms of extended objects such as Wilson loops and holonomies. The loop representation is a quantum hamiltonian representation of gauge theories in terms of loops. The aim of the loop representation in the context of Yang–Mills theories is to avoid the redundancy introduced by Gauss gauge symmetries allowing to work directly in the space of physical states. The idea is well known in the context of lattice Yang–Mills theory. Attempts to explore the continuous loop representation was made by Gambini and Trias for canonical Yang–Mills theory, however there were difficulties as they represented singular objects. As we shall see the loop formalism goes far beyond a simple gauge invariant description, in fact it is the natural geometrical framework to treat gauge theories and quantum gravity in terms of their fundamental physical excitations.

In physics, zilch is a set of ten conserved quantities of the source-free electromagnetic field, which were discovered by Daniel M. Lipkin in 1964. The name refers to the fact that the zilches are only conserved in regions free of electric charge, and therefore have limited physical significance. One of the conserved quantities has an intuitive physical interpretation and is also known as optical chirality.