Greenwashing, also called green sheen, is a form of advertising or marketing spin in which green PR and green marketing are deceptively used to persuade the public that an organization's products, aims, and policies are environmentally friendly. Companies that intentionally take up greenwashing communication strategies often do so to distance themselves from their environmental lapses or those of their suppliers.

Extended producer responsibility (EPR) is a strategy to add all of the estimated environmental costs associated with a product throughout the product life cycle to the market price of that product, contemporarily mainly applied in the field of waste management. Such societal costs are typically externalities to market mechanisms, with a common example being the impact of cars.

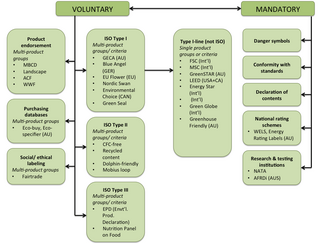

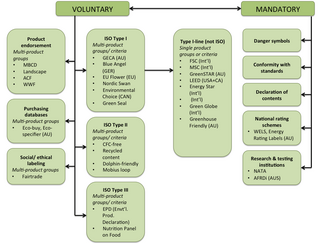

Ecolabels and Green Stickers are labeling systems for food and consumer products. The use of ecolabels is voluntary, whereas green stickers are mandated by law; for example, in North America major appliances and automobiles use Energy Star. They are a form of sustainability measurement directed at consumers, intended to make it easy to take environmental concerns into account when shopping. Some labels quantify pollution or energy consumption by way of index scores or units of measurement, while others assert compliance with a set of practices or minimum requirements for sustainability or reduction of harm to the environment. Many ecolabels are focused on minimising the negative ecological impacts of primary production or resource extraction in a given sector or commodity through a set of good practices that are captured in a sustainability standard. Through a verification process, usually referred to as "certification", a farm, forest, fishery, or mine can show that it complies with a standard and earn the right to sell its products as certified through the supply chain, often resulting in a consumer-facing ecolabel.

Green brands are those brands that consumers associate with environmental conservation and sustainable business practices.

Green marketing is the marketing of products that are presumed to be environmentally safe. It incorporates a broad range of activities, including product modification, changes to the production process, sustainable packaging, as well as modifying advertising. Yet defining green marketing is not a simple task. Other similar terms used are environmental marketing and ecological marketing.

Design for the environment (DfE) is a design approach to reduce the overall human health and environmental impact of a product, process or service, where impacts are considered across its life cycle. Different software tools have been developed to assist designers in finding optimized products or processes/services. DfE is also the original name of a United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) program, created in 1992, that works to prevent pollution, and the risk pollution presents to humans and the environment. The program provides information regarding safer chemical formulations for cleaning and other products. EPA renamed its program "Safer Choice" in 2015.

Sustainable fashion is a term describing efforts within the fashion industry to reduce its environmental impacts, protect workers producing garments, and uphold animal welfare. Sustainability in fashion encompasses a wide range of factors, including cutting CO2 emissions, addressing overproduction, reducing pollution and waste, supporting biodiversity, and ensuring that garment workers are paid a fair wage and have safe working conditions.

A green company, also known as an environmentally friendly or sustainable business, is an organization that conducts itself in a way that minimizes harm to the environment. Examples of these actions may include the conservation of natural resources, efforts to reduce carbon emissions, a reduction of waste creation, and support of ecological conservation. Green companies often implement environmentally responsible practices across their entire value chain, from sourcing raw materials to manufacturing processes and distribution.

Sustainable seafood is seafood that is caught or farmed in ways that consider the long-term vitality of harvested species and the well-being of the oceans, as well as the livelihoods of fisheries-dependent communities. It was first promoted through the sustainable seafood movement which began in the 1990s. This operation highlights overfishing and environmentally destructive fishing methods. Through a number of initiatives, the movement has increased awareness and raised concerns over the way our seafood is obtained.

Sustainable packaging is the development and use of packaging which results in improved sustainability. This involves increased use of life cycle inventory (LCI) and life cycle assessment (LCA) to help guide the use of packaging which reduces the environmental impact and ecological footprint. It includes a look at the whole of the supply chain: from basic function, to marketing, and then through to end of life (LCA) and rebirth. Additionally, an eco-cost to value ratio can be useful The goals are to improve the long term viability and quality of life for humans and the longevity of natural ecosystems. Sustainable packaging must meet the functional and economic needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Sustainability is not necessarily an end state but is a continuing process of improvement.

An eco hotel, or a green hotel, is an environmentally sustainable hotel or accommodation that has made important environmental improvements to its structure in order to minimize its impact on the natural environment. The basic definition of an eco-friendly hotel is an environmentally responsible lodging that follows the practices of green living. These hotels have to be certified green by an independent third-party or by the state they are located in. Traditionally, these hotels were mostly presented as ecolodges because of their location, often in jungles, and their design inspired by the use of traditional building methods applied by skilled local craftsmen in areas, such as Costa Rica and Indonesia.

Electronic waste is a significant part of today's global, post-consumer waste stream. Efforts are being made to recycle and reduce this waste.

An eco-action is any action or activity within a program that is intended to have a positive impact on the environment. For this reason it is often used as a synonym for environmental action. People adopting eco-actions tend to target activities around the ‘Three Rs’ of the waste hierarchy, Reducing, Reusing and Recycling. They may decide to carry out small-scale eco-friendly actions such as reducing the volume of paper used in offices, or purchasing products only from companies that have environmentally friendly or sustainability policies. Others may adopt eco-actions that affect where they live by cleaning up beaches, removing graffiti, supporting community gardening, and re-planting coastal wetlands because the immediate community has come to be considered part of their ecosystem.

Environmentally sustainable design is the philosophy of designing physical objects, the built environment, and services to comply with the principles of ecological sustainability and also aimed at improving the health and comfort of occupants in a building. Sustainable design seeks to reduce negative impacts on the environment, the health and well-being of building occupants, thereby improving building performance. The basic objectives of sustainability are to reduce the consumption of non-renewable resources, minimize waste, and create healthy, productive environments.

Sustainable products are products who are either sustainability sourced, manufactured or processed that provide environmental, social and economic benefits while protecting public health and environment over their whole life cycle, from the extraction of raw materials until the final disposal.

Environmental certification is a form of environmental regulation and development where a company can voluntarily choose to comply with predefined processes or objectives set forth by the certification service. Most certification services have a logo which can be applied to products certified under their standards. This is seen as a form of corporate social responsibility allowing companies to address their obligation to minimise the harmful impacts to the environment by voluntarily following a set of externally set and measured objectives.

Eco-friendly dentistry aims at reducing the detrimental impact of dental services on the environment while still being able to adhere to the regulations and standards of the dental industries in their respective countries.

Green consumption is related to sustainable development or sustainable consumer behaviour. It is a form of consumption that safeguards the environment for the present and for future generations. It ascribes to consumers responsibility or co-responsibility for addressing environmental problems through the adoption of environmentally friendly behaviors, such as the use of organic products, clean and renewable energy, and the choice of goods produced by companies with zero, or almost zero, impact.

The Eco-score, like the Nutri-Score, is a food label with five categories: from A to E. The aim is to help consumers make more ecological choices when making their purchases.

France's anti-waste law for a circular economy was passed in an effort to eliminate improper disposal of waste as well as limit excessive waste. This law is part of Europe's larger environmental activism efforts and builds on previous laws the country has passed.