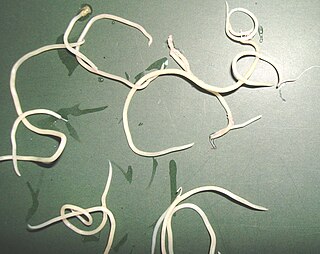

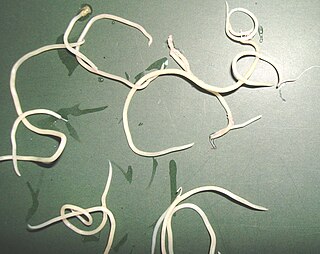

Ascaris lumbricoides is the "large roundworm" of humans, growing to a length of up to 35 cm (14 in). It is one of several species of Ascaris. An ascarid nematode of the phylum Nematoda, it is the most common parasitic worm in humans. This organism is responsible for the disease ascariasis, a type of helminthiasis and one of the group of neglected tropical diseases. An estimated one-sixth of the human population is infected by A. lumbricoides or another roundworm. Ascariasis is prevalent worldwide, especially in tropical and subtropical countries.

In biology and medicine, a host is a larger organism that harbours a smaller organism; whether a parasitic, a mutualistic, or a commensalist guest (symbiont). The guest is typically provided with nourishment and shelter. Examples include animals playing host to parasitic worms, cells harbouring pathogenic (disease-causing) viruses, a bean plant hosting mutualistic (helpful) nitrogen-fixing bacteria. More specifically in botany, a host plant supplies food resources to micropredators, which have an evolutionarily stable relationship with their hosts similar to ectoparasitism. The host range is the collection of hosts that an organism can use as a partner.

Toxocariasis is an illness of humans caused by larvae of either the dog roundworm, or cat roundworm. Toxocariasis is often called visceral larva migrans (VLM). Depending on geographic location, degree of eosinophilia, eye and/or pulmonary signs, the terms ocular larva migrans (OLM), Weingarten's disease, Frimodt-Møller's syndrome, and eosinophilic pseudoleukemia are applied to toxocariasis. Other terms sometimes or rarely used include nematode ophthalmitis, toxocaral disease, toxocarose, and covert toxocariasis. This zoonotic, helminthic infection is a rare cause of blindness and may provoke rheumatic, neurologic, or asthmatic symptoms. Humans normally become infected by ingestion of embryonated eggs from contaminated sources.

Gnathostomiasis is the human infection caused by the nematode (roundworm) Gnathostoma spinigerum and/or Gnathostoma hispidum, which infects vertebrates.

Baylisascaris is a genus of roundworms that infect more than fifty animal species.

Parelaphostrongylus tenuis is a neurotropic nematode parasite common to white-tailed deer, Odocoileus virginianus, which causes damage to the central nervous system. Moose, elk, caribou, mule deer, and others are also susceptible to the parasite, but are aberrant hosts and are infected in neurological instead of meningeal tissue. The frequency of infection in these species increases dramatically when their ranges overlap high densities of white-tailed deer.

Ascaridia galli is a parasitic roundworm belonging to the phylum Nematoda. Nematodes of the genus Ascaridia are essentially intestinal parasites of birds. A. galli is the most prevalent and pathogenic species, especially in domestic fowl, Gallus domesticus. It causes ascaridiasis, a disease of poultry due to heavy worm infection, particularly in chickens and turkeys. It inhabits the small intestine, and can be occasionally seen in commercial eggs.

Spirometra erinaceieuropaei is a parasitic tapeworm that infects domestic animals and humans. The medical term for this infection in humans and other animals is sparganosis. Morphologically, these worms are similar to other worms in the genus Spirometra. They have a long body consisting of three sections: the scolex, the neck, and the strobilia. They have a complex life cycle that consists of three hosts, and can live in varying environments and bodily tissues. Humans can contract this parasite in three main ways. Historically, humans are considered a paratenic host; however, the first case of an adult S. erinaceieuropaei infection in humans was reported in 2017. Spirometra tapeworms exist worldwide and infection is common in animals, but S. erinaceieuropaei infections are rare in humans. Treatment for infection typically includes surgical removal and anti-worm medication.

Mammomonogamus is a genus of parasitic nematodes of the family Syngamidae that parasitise the respiratory tracts of cattle, sheep, goats, deer, cats, orangutans, and elephants. The nematodes can also infect humans and cause the disease called mammomonogamiasis. Several known species fall under the genus Mammomonogamus, but the most common species found to infest humans is M. laryngeus. Infection in humans is very rare, with only about 100 reported cases worldwide, and is assumed to be largely accidental. Cases have been reported from the Caribbean, China, Korea, Thailand, and Philippines.

A gapeworm, also known as a red worm and forked worm, is a parasitic nematode worm that infects the tracheas of certain birds. The resulting disease, known as "gape" occurs when the worms clog and obstruct the airway. The worms are also known as "red worms" or "forked worms" due to their red color and the permanent procreative conjunction of males and females. Gapeworms are common in young, domesticated chickens and turkeys.

Dioctophyme renale, commonly referred to as the giant kidney worm, is a parasitic nematode (roundworm) whose mature form is found in the kidneys of mammals. D. renale is distributed worldwide, but is less common in Africa and Oceania. It affects fish eating mammals, particularly mink and dogs. Human infestation is rare, but results in kidney destruction, usually of one kidney and hence not fatal. A 2019 review listed a total of 37 known human cases of dioctophymiasis in 10 countries with the highest number (22) in China. Upon diagnosis through tissue sampling, the only treatment is surgical excision.

Toxocara canis is a worldwide-distributed helminth parasite of dogs and other canids. The name is derived from the Greek word "toxon," meaning bow or quiver, and the Latin word "caro," meaning flesh. They live in the small intestine of the definitive host. In adult dogs, the infection is usually asymptomatic but may be characterized by diarrhea. By contrast, massive infection with Toxocara canis can be fatal in puppies, causing diarrhea, vomiting, an enlarged abdomen, flatulence, and poor growth rate.

Capillaria philippinensis is a parasitic nematode which causes intestinal capillariasis. This sometimes fatal disease was first discovered in Northern Luzon, Philippines in 1964. Cases have also been reported from China, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Japan, Korea, Lao PDR, Taiwan and Thailand. Cases diagnosed in Italy and Spain were believed to be acquired abroad, with one case possibly contracted in Colombia. The natural life cycle of C. philippinensis is believed to involve fish as intermediate hosts, and fish-eating birds as definitive hosts. Humans acquire C. philippinensis by eating small species of infested fish whole and raw.

Heterakis gallinarum is a nematode parasite that lives in the cecum of some galliform birds, particularly in ground feeders such as domestic chickens and turkeys. It causes infection that is mildly pathogenic. However, it often carries a protozoan parasite Histomonas meleagridis which causes of histomoniasis. Transmission of H. meleagridis is through the H. gallinarum egg. H. gallinarum is about 1–2 cm in length with a sharply pointed tail and a preanal sucker. The parasite is a diecious species with marked sexual dimorphism. Males are smaller and shorter, measuring around 9 mm in length, with a unique bent tail. Females are stouter and longer, measuring roughly 13 mm in length, with a straight tail end.

Baylisascaris procyonis, common name raccoon roundworm, is a roundworm nematode, found ubiquitously in raccoons, the definitive hosts. It is named after H. A. Baylis, who studied them in the 1920s–30s, and Greek askaris. Baylisascaris larvae in paratenic hosts can migrate, causing visceral larva migrans (VLM). Baylisascariasis as the zoonotic infection of humans is rare, though extremely dangerous due to the ability of the parasite's larvae to migrate into brain tissue and cause damage. Concern for human infection has been increasing over the years due to urbanization of rural areas resulting in the increase in proximity and potential human interaction with raccoons.

Gnathostoma hispidum is a nematode (roundworm) that infects many vertebrate animals including humans. Infection of Gnathostoma hispidum, like many species of Gnathostoma causes the disease gnathostomiasis due to the migration of immature worms in the tissues.

Histomoniasis is a commercially significant disease of poultry, particularly of chickens and turkeys, due to parasitic infection of a protozoan, Histomonas meleagridis. The protozoan is transmitted to the bird by the nematode parasite Heterakis gallinarum. H. meleagridis resides within the eggs of H. gallinarum, so birds ingest the parasites along with contaminated soil or food. Earthworms can also act as a paratenic host.

Anisakis simplex, known as the herring worm, is a species of nematode in the genus Anisakis. Like other nematodes, it infects and settles in the organs of marine animals, such as salmon, mackerels and squids. It is commonly found in cold marine waters, such as the Pacific Ocean and Atlantic Ocean.

Baylisascaris shroederi, common name giant panda roundworm, is a roundworm (nematode), found ubiquitously in giant pandas of central China, the definitive hosts. Baylisascaris larvae in paratenic hosts can migrate, causing visceral larva migrans (VLM). It is extremely dangerous to the host due to the ability of the parasite's larvae to migrate into brain tissue and cause damage. Concern for human infection is minimal as there are very few giant pandas living today and most people do not encounter giant pandas in their everyday activities. There is growing recognition that the infection of Baylisascaris shroederi is one of the major causes of death in the species. This is confirmed by a report stating that during the period of 2001 to 2005; about 50% of deaths in wild giant pandas were caused by the parasite infection.

Corynosoma autrale is a species of acanthocephalan. This species usually infects pinnipeds; the semi-aquatic fin-footed marine mammals most commonly known as seals and sea lions. Pinniped infections are not exclusive, recently C. australe has been discovered in Magellanic penguins.