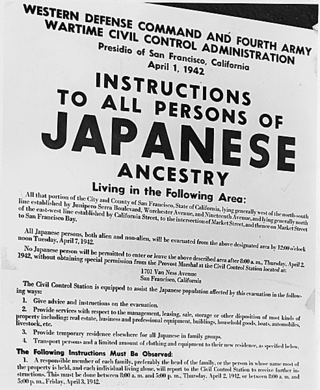

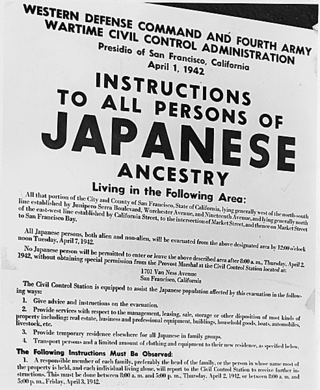

Executive Order 9066 was a United States presidential executive order signed and issued during World War II by United States president Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942. "This order authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to "relocation centers" further inland—resulting in the incarceration of Japanese Americans." Two-thirds of the 125,000 people displaced were U.S. citizens.

During World War II, the United States, by order of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, forcibly relocated and incarcerated at least 125,284 people of Japanese descent in 75 identified incarceration sites. Most lived on the Pacific Coast, in concentration camps in the western interior of the country. Approximately two-thirds of the inmates were United States citizens. These actions were initiated by Executive Order 9066 following Imperial Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor. Like many Americans at the time, the architects of the removal policy failed to distinguish between Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans. Of the 127,000 Japanese Americans who were living in the continental United States at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, 112,000 resided on the West Coast. About 80,000 were Nisei and Sansei. The rest were Issei immigrants born in Japan who were ineligible for U.S. citizenship under U.S. law.

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944), was a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that upheld the internment of Japanese Americans from the West Coast Military Area during World War II. The decision has been widely criticized, with some scholars describing it as "an odious and discredited artifact of popular bigotry", and as "a stain on American jurisprudence". The case is often cited as one of the worst Supreme Court decisions of all time. Chief Justice John Roberts repudiated the Korematsu decision in his majority opinion in the 2018 case of Trump v. Hawaii.

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was a United States government agency established to handle the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It also operated the Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter in Oswego, New York, which was the only refugee camp set up in the United States for refugees from Europe. The agency was created by Executive Order 9102 on March 18, 1942, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and was terminated June 26, 1946, by order of President Harry S. Truman.

The Tule Lake National Monument in Modoc and Siskiyou counties in California, consists primarily of the site of the Tule Lake War Relocation Center, one of ten concentration camps constructed in 1942 by the United States government to incarcerate Japanese Americans forcibly removed from their homes on the West Coast. They totaled nearly 120,000 people, more than two-thirds of whom were United States citizens. Among the inmates, the notation "鶴嶺湖" was sometimes applied.

Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu was an American civil rights activist who resisted the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. Shortly after the Imperial Japanese Navy launched its attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized the removal of individuals of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast from their homes and their mandatory imprisonment in incarceration camps, but Korematsu instead challenged the orders and became a fugitive.

Ex parte Quirin, 317 U.S. 1 (1942), was a case of the United States Supreme Court that during World War II upheld the jurisdiction of a United States military tribunal over the trial of eight German saboteurs, in the United States. Quirin has been cited as a precedent for the trial by military commission of unlawful combatants.

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81 (1943), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court held that the application of curfews against members of a minority group were constitutional when the nation was at war with the country from which that group's ancestors originated. The case arose out of the issuance of Executive Order 9066 following the attack on Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entry into World War II. President Franklin D. Roosevelt had authorized military commanders to secure areas from which "any or all persons may be excluded", and Japanese Americans living in the West Coast were subject to a curfew and other restrictions before being removed to internment camps. The plaintiff, Gordon Hirabayashi, was convicted of violating the curfew and had appealed to the Supreme Court. Yasui v. United States was a companion case decided the same day. Both convictions were overturned in coram nobis proceedings in the 1980s.

The Topaz War Relocation Center, also known as the Central Utah Relocation Center (Topaz) and briefly as the Abraham Relocation Center, was an American concentration camp in which Americans of Japanese descent and immigrants who had come to the United States from Japan, called Nikkei were incarcerated. President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, ordering people of Japanese ancestry to be incarcerated in what were euphemistically called "relocation centers" like Topaz during World War II. Most of the people incarcerated at Topaz came from the Tanforan Assembly Center and previously lived in the San Francisco Bay Area. The camp was opened in September 1942 and closed in October 1945.

On February 19, 1942, shortly after Japan's surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 authorizing the forced removal of over 110,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast and into internment camps for the duration of the war. The personal rights, liberties, and freedoms of Japanese Americans were suspended by the United States government. In the "relocation centers", internees were housed in tar-papered army-style barracks. Some individuals who protested their treatment were sent to a special camp at Tule Lake, California.

The following article focuses on the movement to obtain redress for the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, and significant court cases that have shaped civil and human rights for Japanese Americans and other minorities. These cases have been the cause and/or catalyst to many changes in United States law. But mainly, they have resulted in adjusting the perception of Asian immigrants in the eyes of the American government.

Yasui v. United States, 320 U.S. 115 (1943), was a United States Supreme Court case regarding the constitutionality of curfews used during World War II when they were applied to citizens of the United States. The case arose out of the implementation of Executive Order 9066 by the U.S. military to create zones of exclusion along the West Coast of the United States, where Japanese Americans were subjected to curfews and eventual removal to relocation centers. This Presidential order followed the attack on Pearl Harbor that brought America into World War II and inflamed the existing anti-Japanese sentiment in the country.

Duncan v. Kahanamoku, 327 U.S. 304 (1946), was a decision by the United States Supreme Court. It is often associated with the Japanese exclusion cases because it involved wartime curtailment of fundamental civil liberties under the aegis of military authority, though in this case neither the plaintiff nor the nominal defendant were Japanese.

Wayne Mortimer Collins was a civil rights attorney who worked on cases related to the Japanese American evacuation and internment.

Mitsuye "Maureen" Endo Tsutsumi was an American woman of Japanese descent who was placed in an internment camp during World War II. Endo filed a writ of habeas corpus that ultimately led to a United States Supreme Court ruling that the U.S. government could not continue to detain a citizen who was "concededly loyal" to the United States.

Wong Wing v. United States, 163 U.S. 228 (1896), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court found that the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution forbid the imprisonment at hard labor without a jury trial for noncitizens convicted of illegal entry to or presence in the United States.

The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS) was a research project funded by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), an agency responsible for overseeing the relocation of Japanese Americans, The University of California, the Giannini Foundation, the Columbian Foundation, and the Rockefeller Foundation with the total amount of funding reaching almost 100,000 U.S. dollars. It was conducted by a team of social scientists at the University of California, Berkeley. The team was led by sociologist Dorothy Swaine Thomas, a Lecturer in Sociology for the Giannini Foundation and a professor of rural sociology, and included anthropologists John Collier Jr. and Alexander Leighton, among others. The study combined each of the major social sciences such as sociology, social anthropology, political science, social psychology, and economics to effectively illustrate the effects of internment on Japanese Americans. The terminology of "relocation" can be confusing: The WRA termed the forced removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast an "evacuation" and called the incarceration of these people in the ten camps as "relocation." Later it also applied the term "relocation" to the program that enabled the evacuees to leave the camps (provided they had been certified as loyal.

An anticanon is a legal text that is now viewed as wrongly reasoned or decided. The term "anticanon" stands in distinction to the canon, which contains basic principles or rulings that almost all people support.

Taneyuki “Dan” Harada was a Japanese-American painter and computer scientist who was incarcerated at Tanforan Assembly Center, Topaz War Relocation Center, Leupp Isolation Center, and Tule Lake Segregation Center during World War II. His paintings capture the experience of Japanese-Americans in concentration camp life, including the segregation, isolation, and discrimination they faced. He learned to paint at various art schools while detained, and continued studying at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, California after being released at the end of the war. He was the recipient of the James D. Phelan Art Award, established to recognize the achievements of California-born artists across many disciplines, in 1949. Today, pieces of his collections are held at the San Francisco Fine Art Museum, the Autry Museum of Western Heritage, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art