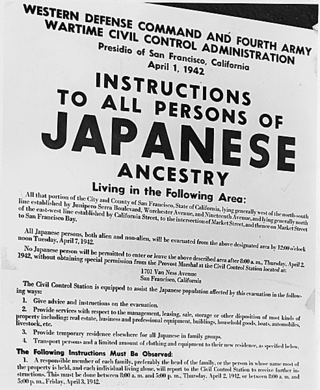

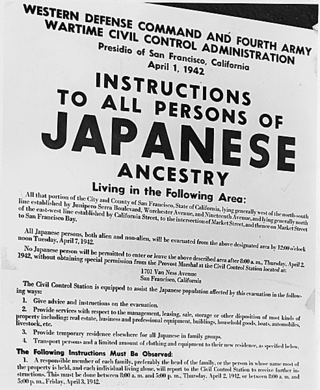

Executive Order 9066 was a United States presidential executive order signed and issued during World War II by United States president Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942. "This order authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to "relocation centers" further inland—resulting in the incarceration of Japanese Americans." Two-thirds of them were U.S. citizens, born and raised in the United States.

During World War II, the United States forcibly relocated and incarcerated at least 125,284 people of Japanese descent in 75 identified incarceration sites. Most lived on the Pacific Coast, in concentration camps in the western interior of the country. Approximately two-thirds of the inmates were United States citizens. These actions were initiated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt via Executive Order 9066 following Imperial Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor.

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944), was a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that upheld the internment of Japanese Americans from the West Coast Military Area during World War II. The decision has been widely criticized, with some scholars describing it as "an odious and discredited artifact of popular bigotry", and as "a stain on American jurisprudence". The case is often cited as one of the worst Supreme Court decisions of all time. Chief Justice John Roberts repudiated the Korematsu decision in his majority opinion in the 2018 case of Trump v. Hawaii.

Ex parte Mitsuye Endo, 323 U.S. 283 (1944), was a United States Supreme Court ex parte decision handed down on December 18, 1944, in which the Justices unanimously ruled that the U.S. government could not continue to detain a citizen who was "concededly loyal" to the United States. Although the Court did not touch on the constitutionality of the exclusion of people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast, which it had found not to violate citizen rights in its Korematsu v. United States decision on the same date, the Endo ruling nonetheless led to the reopening of the West Coast to Japanese Americans after their incarceration in camps across the U.S. interior during World War II.

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was a United States government agency established to handle the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It also operated the Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter in Oswego, New York, which was the only refugee camp set up in the United States for refugees from Europe. The agency was created by Executive Order 9102 on March 18, 1942, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and was terminated June 26, 1946, by order of President Harry S. Truman.

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 is a United States federal law that granted reparations to Japanese Americans who had been wrongly interned by the United States government during World War II and to "discourage the occurrence of similar injustices and violations of civil liberties in the future". The act was sponsored by California Democratic congressman and former internee Norman Mineta, Wyoming Republican senator Alan K. Simpson and California senator Pete Wilson. The bill was supported by the majority of Democrats in Congress, while the majority of Republicans voted against it. The act was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan.

Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu was an American civil rights activist who resisted the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. Shortly after the Imperial Japanese Navy launched its attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized the removal of individuals of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast from their homes and their mandatory imprisonment in incarceration camps, but Korematsu instead challenged the orders and became a fugitive.

Gordon Kiyoshi Hirabayashi was an American sociologist, best known for his principled resistance to the Japanese American internment during World War II, and the court case which bears his name, Hirabayashi v. United States.

John Lesesne DeWitt was a three-star general in the United States Army, best known for overseeing the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

On February 19, 1942, shortly after Japan's surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 authorizing the forced removal of over 110,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast and into internment camps for the duration of the war. The personal rights, liberties, and freedoms of Japanese Americans were suspended by the United States government. In the "relocation centers", internees were housed in tar-papered army-style barracks. Some individuals who protested their treatment were sent to a special camp at Tule Lake, California.

The following article focuses on the movement to obtain redress for the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, and significant court cases that have shaped civil and human rights for Japanese Americans and other minorities. These cases have been the cause and/or catalyst to many changes in United States law. But mainly, they have resulted in adjusting the perception of Asian immigrants in the eyes of the American government.

Minoru Yasui was an American lawyer from Oregon. Born in Hood River, Oregon, he earned both an undergraduate degree and his law degree at the University of Oregon. He was one of the few Japanese Americans after the bombing of Pearl Harbor who fought laws that directly targeted Japanese Americans or Japanese immigrants. His case was the first case to test the constitutionality of the curfews targeted at minority groups.

Yasui v. United States, 320 U.S. 115 (1943), was a United States Supreme Court case regarding the constitutionality of curfews used during World War II when they were applied to citizens of the United States. The case arose out of the implementation of Executive Order 9066 by the U.S. military to create zones of exclusion along the West Coast of the United States, where Japanese Americans were subjected to curfews and eventual removal to relocation centers. This Presidential order followed the attack on Pearl Harbor that brought America into World War II and inflamed the existing anti-Japanese sentiment in the country.

Charles Fahy was an American lawyer and judge who served as the 26th Solicitor General of the United States from 1941 to 1945 and later served as a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit from 1949 until his death in 1979.

James Alger Fee was a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and previously was a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of Oregon. A veteran of the United States Army, his first judicial position was with the Oregon Circuit Court. While a federal judge he made national news for his decision during World War II regarding the application of the exclusion orders that had forced those of Japanese heritage from the West Coast.

Harold Evans, a Philadelphia attorney, was appointed by the United Nations to be the first Special Municipal Commissioner for Jerusalem on May 13, 1948. Evans arrived in Cairo, Egypt on May 23, 1948, but due to his Quaker religious principles he would not travel with a British military escort from Cairo to Jerusalem. He eventually arrived in Jerusalem in early June, but abruptly resigned his position afterward.

Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga was a Japanese American political activist who played a major role in the Japanese American redress movement. She was the lead researcher of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC), a bipartisan federal committee appointed by Congress in 1980 to review the causes and effects of the Japanese American incarceration during World War II. As a young woman, Herzig-Yoshinaga was confined in the Manzanar Concentration Camp in California, the Jerome War Relocation Center in Arkansas, and the Rohwer War Relocation Center, which is also in Arkansas. She later uncovered government documents that debunked the wartime administration's claims of "military necessity" and helped compile the CWRIC's final report, Personal Justice Denied, which led to the issuance of a formal apology and reparations for former camp inmates. She also contributed pivotal evidence and testimony to the Hirabayashi, Korematsu and Yasui coram nobis cases.

Hirabayashi v. United States, 828 F.2d 591, is a case decided by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals and recognized for both its historical and legal significance. The case is historically significant for vacating the World War II–era convictions of Japanese American civil rights leader Gordon Hirabayashi. Those convictions were affirmed in the Supreme Court's 1943 decision Hirabayashi v. United States. The case is legally significant for establishing the standard to determine when any federal court in the Ninth Circuit may issue a writ of coram nobis.

Cherry Kinoshita was a Japanese American activist and leader in the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). She helped found the Seattle Evacuation Redress Committee and fought for financial compensation for Japanese Americans who had been incarcerated during World War II.