Otorhinolaryngology is a surgical subspecialty within medicine that deals with the surgical and medical management of conditions of the head and neck. Doctors who specialize in this area are called otorhinolaryngologists, otolaryngologists, head and neck surgeons, or ENT surgeons or physicians. Patients seek treatment from an otorhinolaryngologist for diseases of the ear, nose, throat, base of the skull, head, and neck. These commonly include functional diseases that affect the senses and activities of eating, drinking, speaking, breathing, swallowing, and hearing. In addition, ENT surgery encompasses the surgical management of cancers and benign tumors and reconstruction of the head and neck as well as plastic surgery of the face, scalp, and neck.

Ramsay Hunt syndrome type 2, commonly referred to simply as Ramsay Hunt syndrome (RHS) and also known as herpes zoster oticus, is inflammation of the geniculate ganglion of the facial nerve as a late consequence of varicella zoster virus (VZV). In regard to the frequency, less than 1% of varicella zoster infections involve the facial nerve and result in RHS. It is traditionally defined as a triad of ipsilateral facial paralysis, otalgia, and vesicles close to the ear and auditory canal. Due to its proximity to the vestibulocochlear nerve, the virus can spread and cause hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo. It is common for diagnoses to be overlooked or delayed, which can raise the likelihood of long-term consequences. It is more complicated than Bell's palsy. Therapy aims to shorten its overall length, while also providing pain relief and averting any consequences.

Bell's palsy is a type of facial paralysis that results in a temporary inability to control the facial muscles on the affected side of the face. In most cases, the weakness is temporary and significantly improves over weeks. Symptoms can vary from mild to severe. They may include muscle twitching, weakness, or total loss of the ability to move one or, in rare cases, both sides of the face. Other symptoms include drooping of the eyebrow, a change in taste, and pain around the ear. Typically symptoms come on over 48 hours. Bell's palsy can trigger an increased sensitivity to sound known as hyperacusis.

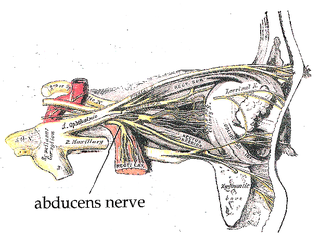

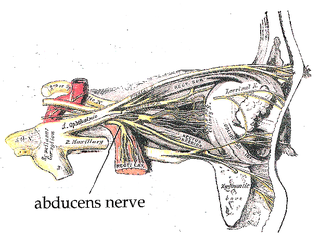

The abducens nerve or abducent nerve, also known as the sixth cranial nerve, cranial nerve VI, or simply CN VI, is a cranial nerve in humans and various other animals that controls the movement of the lateral rectus muscle, one of the extraocular muscles responsible for outward gaze. It is a somatic efferent nerve.

The parotid gland is a major salivary gland in many animals. In humans, the two parotid glands are present on either side of the mouth and in front of both ears. They are the largest of the salivary glands. Each parotid is wrapped around the mandibular ramus, and secretes serous saliva through the parotid duct into the mouth, to facilitate mastication and swallowing and to begin the digestion of starches. There are also two other types of salivary glands; they are submandibular and sublingual glands. Sometimes accessory parotid glands are found close to the main parotid glands.

Ear pain, also known as earache or otalgia, is pain in the ear. Primary ear pain is pain that originates from the ear. Secondary ear pain is a type of referred pain, meaning that the source of the pain differs from the location where the pain is felt.

Neuritis, from the Greek νεῦρον), is inflammation of a nerve or the general inflammation of the peripheral nervous system. Inflammation, and frequently concomitant demyelination, cause impaired transmission of neural signals and leads to aberrant nerve function. Neuritis is often conflated with neuropathy, a broad term describing any disease process which affects the peripheral nervous system. However, neuropathies may be due to either inflammatory or non-inflammatory causes, and the term encompasses any form of damage, degeneration, or dysfunction, while neuritis refers specifically to the inflammatory process.

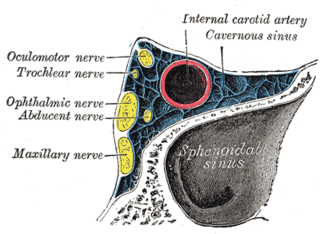

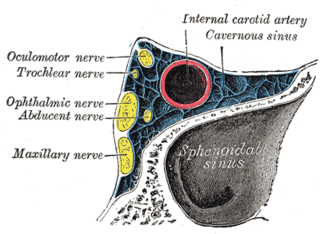

Sixth nerve palsy, or abducens nerve palsy, is a disorder associated with dysfunction of cranial nerve VI, which is responsible for causing contraction of the lateral rectus muscle to abduct the eye. The inability of an eye to turn outward, results in a convergent strabismus or esotropia of which the primary symptom is diplopia in which the two images appear side-by-side. Thus, the diplopia is horizontal and worse in the distance. Diplopia is also increased on looking to the affected side and is partly caused by overaction of the medial rectus on the unaffected side as it tries to provide the extra innervation to the affected lateral rectus. These two muscles are synergists or "yoke muscles" as both attempt to move the eye over to the left or right. The condition is commonly unilateral but can also occur bilaterally.

Cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST) is the formation of a blood clot within the cavernous sinus, a cavity at the base of the brain which drains deoxygenated blood from the brain back to the heart. This is a rare disorder and can be of two types–septic cavernous thrombosis and aseptic cavernous thrombosis. The most common form is septic cavernous sinus thrombosis. The cause is usually from a spreading infection in the nose, sinuses, ears, or teeth. Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus are often the associated bacteria.

Fazio–Londe disease (FLD), also called progressive bulbar palsy of childhood, is a very rare inherited motor neuron disease of children and young adults and is characterized by progressive paralysis of muscles innervated by cranial nerves. FLD, along with Brown–Vialetto–Van Laere syndrome (BVVL), are the two forms of infantile progressive bulbar palsy, a type of progressive bulbar palsy in children.

Foix–Chavany–Marie syndrome (FCMS), also known as bilateral opercular syndrome, is a neuropathological disorder characterized by paralysis of the facial, tongue, pharynx, and masticatory muscles of the mouth that aid in chewing. The disorder is primarily caused by thrombotic and embolic strokes, which cause a deficiency of oxygen in the brain. As a result, bilateral lesions may form in the junctions between the frontal lobe and temporal lobe, the parietal lobe and cortical lobe, or the subcortical region of the brain. FCMS may also arise from defects existing at birth that may be inherited or nonhereditary. Symptoms of FCMS can be present in a person of any age and it is diagnosed using automatic-voluntary dissociation assessment, psycholinguistic testing, neuropsychological testing, and brain scanning. Treatment for FCMS depends on the onset, as well as on the severity of symptoms, and it involves a multidisciplinary approach.

Vocal cord paresis, also known as recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis or vocal fold paralysis, is an injury to one or both recurrent laryngeal nerves (RLNs), which control all intrinsic muscles of the larynx except for the cricothyroid muscle. The RLN is important for speaking, breathing and swallowing.

Tolosa–Hunt syndrome is a rare disorder characterized by severe and unilateral headaches with orbital pain, along with weakness and paralysis (ophthalmoplegia) of certain eye muscles.

Synkinesis is a neurological symptom in which a voluntary muscle movement causes the simultaneous involuntary contraction of other muscles. An example might be smiling inducing an involuntary contraction of the eye muscles, causing a person to squint when smiling. Facial and extraocular muscles are affected most often; in rare cases, a person's hands might perform mirror movements.

Posterior spinal artery syndrome(PSAS), also known as posterior spinal cord syndrome, is a type of incomplete spinal cord injury. PSAS is the least commonly occurring of the six clinical spinal cord injury syndromes, with an incidence rate of less than 1%.

Cranial nerve disease is an impaired functioning of one of the twelve cranial nerves. Although it could theoretically be considered a mononeuropathy, it is not considered as such under MeSH.

Heerfordt syndrome is a rare manifestation of sarcoidosis. The symptoms include inflammation of the eye (uveitis), swelling of the parotid gland, chronic fever, and in some cases, palsy of the facial nerves.

Otitis externa, also called swimmer's ear, is inflammation of the ear canal. It often presents with ear pain, swelling of the ear canal, and occasionally decreased hearing. Typically there is pain with movement of the outer ear. A high fever is typically not present except in severe cases.

Alternating hemiplegia is a form of hemiplegia that has an ipsilateral cranial nerve palsies and contralateral hemiplegia or hemiparesis of extremities of the body. The disorder is characterized by recurrent episodes of paralysis on one side of the body. There are multiple forms of alternating hemiplegia, Weber's syndrome, middle alternating hemiplegia, and inferior alternating hemiplegia. This type of syndrome can result from a unilateral lesion in the brainstem affecting both upper motor neurons and lower motor neurons. The muscles that would receive signals from these damaged upper motor neurons result in spastic paralysis. With a lesion in the brainstem, this affects the majority of limb and trunk muscles on the contralateral side due to the upper motor neurons decussation after the brainstem. The cranial nerves and cranial nerve nuclei are also located in the brainstem making them susceptible to damage from a brainstem lesion. Cranial nerves III (Oculomotor), VI (Abducens), and XII (Hypoglossal) are most often associated with this syndrome given their close proximity with the pyramidal tract, the location which upper motor neurons are in on their way to the spinal cord. Damages to these structures produce the ipsilateral presentation of paralysis or palsy due to the lack of cranial nerve decussation before innervating their target muscles. The paralysis may be brief or it may last for several days, many times the episodes will resolve after sleep. Some common symptoms of alternating hemiplegia are mental impairment, gait and balance difficulties, excessive sweating and changes in body temperature.

Facial nerve decompression is a type of nerve decompression surgery where abnormal compression on the facial nerve is relieved.