The Bantu languages are a language family of about 600 languages that are spoken by the Bantu peoples of Central, Southern, Eastern and Southeast Africa. They form the largest branch of the Southern Bantoid languages.

South African English is the set of English language dialects native to South Africans.

Zulu, or isiZulu as an endonym, is a Southern Bantu language of the Nguni branch spoken and indigenous to Southern Africa. It is the language of the Zulu people, with about 13.56 million native speakers, who primarily inhabit the province of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa. Zulu is the most widely spoken home language in South Africa, and it is understood by over 50% of its population. It became one of South Africa's 12 official languages in 1994.

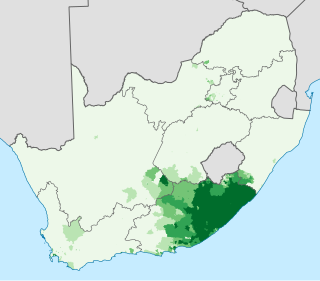

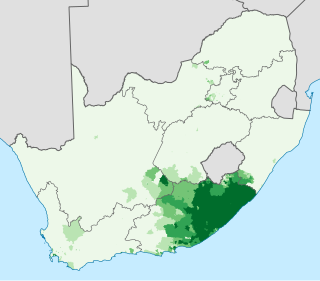

Xhosa, formerly spelled Xosa and also known by its local name isiXhosa, is a Nguni language, indigenous to Southern Africa and one of the official languages of South Africa and Zimbabwe. Xhosa is spoken as a first language by approximately 10 million people and as a second language by another 10 million, mostly in South Africa, particularly in Eastern Cape, Western Cape, Northern Cape and Gauteng, and also in parts of Zimbabwe and Lesotho. It has perhaps the heaviest functional load of click consonants in a Bantu language, with one count finding that 10% of basic vocabulary items contained a click.

isiNdebele, also known as Southern Ndebele is an African language belonging to the Mbo group of Bantu languages, spoken by the Ndebele people of South Africa.

Tsonga or, natively, Xitsonga, as an endonym, is a Bantu language spoken by the Tsonga people of South Africa. It is mutually intelligible with Tswa and Ronga and the name "Tsonga" is often used as a cover term for all three, also sometimes referred to as Tswa-Ronga. The Xitsonga language has been standardised for both academic and home use. Tsonga is an official language of South Africa, and under the name "Shangani" it is recognised as an official language in the Constitution of Zimbabwe. All Tswa-Ronga languages are recognised in Mozambique. It is not official in Eswatini.

Kraal is an Afrikaans and Dutch word, also used in South African English, for an enclosure for cattle or other livestock, located within a Southern African settlement or village surrounded by a fence of thorn-bush branches, a palisade, mud wall, or other fencing, roughly circular in form. It is similar to a boma in eastern or central Africa.

At least thirty-five languages are spoken in South Africa, twelve of which are official languages of South Africa: Ndebele, Pedi, Sotho, South African Sign Language, Swazi, Tsonga, Tswana, Venda, Afrikaans, Xhosa, Zulu and English, which is the primary language used in parliamentary and state discourse, though all official languages are equal in legal status. In addition, South African Sign Language was recognised as the twelfth official language of South Africa by the National Assembly on 3 May 2023. Unofficial languages are protected under the Constitution of South Africa, though few are mentioned by any name.

Kaffir, also spelled Cafri, is an exonym and an ethnic slur – the use of it in reference to black people being particularly common in South Africa. In Arabic, the word kāfir ("unbeliever") was originally applied to non-Muslims before becoming predominantly focused on pagan zanj who were increasingly used as slaves. During the Age of Exploration in early modern Europe, variants of the Latin term cafer were adopted in reference to non-Muslim Bantu peoples even when they were monotheistic. It was eventually used, particularly in Afrikaans, for any black person during the Apartheid and Post-Apartheid eras, closely associated with South African racism, it became a pejorative by the mid-20th century and is now considered extremely offensive hate speech. Punishing continuing use of the term was one of the concerns of the Promotion of Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act enacted by the South African parliament in the year 2000 and it is now euphemistically addressed as the K-word in South African English.

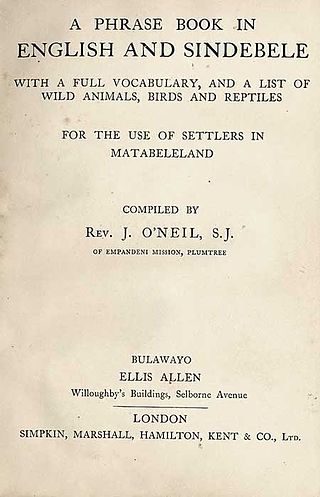

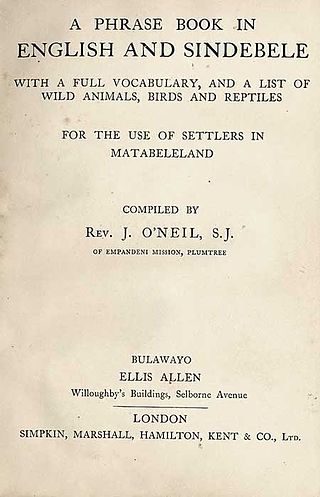

Northern Ndebele, also called Ndebele, isiNdebele saseNyakatho, Zimbabwean Ndebele or North Ndebele, associated with the term Matabele, is a Bantu language spoken by the Northern Ndebele people which belongs to the Nguni group of languages.

Kaffir or Kafir may refer to:

Tsotsitaal is a South African vernacular dialect derived from a variety of mixed languages mainly spoken in the townships of Gauteng province, but also in other agglomerations all over South Africa. Tsotsi is a Sesotho, Pedi or Tswana slang word for a "thug" or "robber" or "criminal", possibly from the verb "ho lotsa" "to sharpen", whose meaning has been modified in modern times to include "to con"; or from the tsetse fly, as the language was first known as Flytaal, although flaai also means "cool" or "street smart". The word taal in Afrikaans means "language".

Zambia has several major indigenous languages, all members of the Bantu family, as well as Khwedam, Zambian Sign Language, several immigrant languages and the pidgins Settla and Fanagalo. English is the official language and the major language of business and education.

The phonology of Sesotho and those of the other Sotho–Tswana languages are radically different from those of "older" or more "stereotypical" Bantu languages. Modern Sesotho in particular has very mixed origins inheriting many words and idioms from non-Sotho–Tswana languages.

The Nguni people are a linguistic cultural group that migrated to South Africa, made up of Bantu ethnic groups from central Africa, with offshoots in neighboring countries in Southern Africa. Swazi people live in both South Africa and Eswatini, while Ndebele people live in both South Africa and Zimbabwe.

Tswa (Xitswa) is a South-Eastern Bantu language in Southern Mozambique. Its closest relatives are Ronga and Tsonga, the three forming the Tswa–Ronga family of languages.

Many languages are spoken, or historically have been spoken, in Zimbabwe. Since the adoption of its 2013 Constitution, Zimbabwe has 16 official languages, namely Chewa, Chibarwe, English, Kalanga, Koisan, Nambya, Ndau, Ndebele, Shangani, Shona, sign language, Sotho, Tonga, Tswana, Venda, Xhosa. The country's main languages are Shona, spoken by only 42% of the population, and Ndebele, spoken by roughly 39%. English is the country's lingua franca, used in government and business and as the main medium of instruction in schools. English is the first language of most white Zimbabweans, and is the second language of a majority of black Zimbabweans. Historically, a minority of white Zimbabweans spoke Afrikaans, Greek, Italian, Polish, and Portuguese, among other languages, while Gujarati and Hindi could be found amongst the country's Indian population. Deaf Zimbabweans commonly use one of several varieties of Zimbabwean Sign Language, with some using American Sign Language. Zimbabwean language data is based on estimates, as Zimbabwe has never conducted a census that enumerated people by language.

Most words of African origin used in English are nouns describing animals, plants, or cultural practices that have their origins in Africa. The following list includes some examples.