Related Research Articles

A cathode is the electrode from which a conventional current leaves a polarized electrical device. This definition can be recalled by using the mnemonic CCD for Cathode Current Departs. A conventional current describes the direction in which positive charges move. Electrons have a negative electrical charge, so the movement of electrons is opposite to that of the conventional current flow. Consequently, the mnemonic cathode current departs also means that electrons flow into the device's cathode from the external circuit. For example, the end of a household battery marked with a + (plus) is the cathode.

Electrochemistry is the branch of physical chemistry concerned with the relationship between electrical potential difference, as a measurable and quantitative phenomenon, and identifiable chemical change, with the potential difference as an outcome of a particular chemical change, or vice versa. These reactions involve electrons moving via an electronically-conducting phase between electrodes separated by an ionically conducting and electronically insulating electrolyte.

An electrochemical cell is a device that generates electrical energy from chemical reactions. Electrical energy can also be applied to these cells to cause chemical reactions to occur. Electrochemical cells which generate an electric current are called voltaic or galvanic cells and those that generate chemical reactions, via electrolysis for example, are called electrolytic cells.

In chemistry and manufacturing, electrolysis is a technique that uses direct electric current (DC) to drive an otherwise non-spontaneous chemical reaction. Electrolysis is commercially important as a stage in the separation of elements from naturally occurring sources such as ores using an electrolytic cell. The voltage that is needed for electrolysis to occur is called the decomposition potential. The word "lysis" means to separate or break, so in terms, electrolysis would mean "breakdown via electricity".

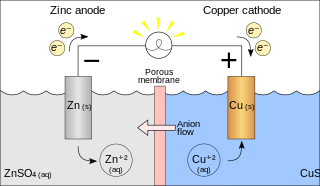

A galvanic cell or voltaic cell, named after the scientists Luigi Galvani and Alessandro Volta, respectively, is an electrochemical cell in which an electric current is generated from spontaneous Oxidation-Reduction reactions. A common apparatus generally consists of two different metals, each immersed in separate beakers containing their respective metal ions in solution that are connected by a salt bridge or separated by a porous membrane.

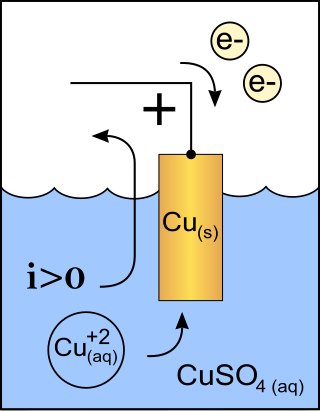

An electrolytic cell is an electrochemical cell that utilizes an external source of electrical energy to force a chemical reaction that would otherwise not occur. The external energy source is a voltage applied between the cell′s two electrodes; an anode and a cathode, which are immersed in an electrolyte solution. This is in contrast to a galvanic cell, which itself is a source of electrical energy and the foundation of a battery. The net reaction taking place in a galvanic cell is a spontaneous reaction, i.e, the Gibbs free energy remains -ve, while the net reaction taking place in an electrolytic cell is the reverse of this spontaneous reaction, i.e, the Gibbs free energy is +ve.

The chloralkali process is an industrial process for the electrolysis of sodium chloride (NaCl) solutions. It is the technology used to produce chlorine and sodium hydroxide, which are commodity chemicals required by industry. Thirty five million tons of chlorine were prepared by this process in 1987. The chlorine and sodium hydroxide produced in this process are widely used in the chemical industry.

A regenerative fuel cell or reverse fuel cell (RFC) is a fuel cell run in reverse mode, which consumes electricity and chemical B to produce chemical A. By definition, the process of any fuel cell could be reversed. However, a given device is usually optimized for operating in one mode and may not be built in such a way that it can be operated backwards. Standard fuel cells operated backwards generally do not make very efficient systems unless they are purpose-built to do so as with high-pressure electrolysers, regenerative fuel cells, solid-oxide electrolyser cells and unitized regenerative fuel cells.

A proton-exchange membrane, or polymer-electrolyte membrane (PEM), is a semipermeable membrane generally made from ionomers and designed to conduct protons while acting as an electronic insulator and reactant barrier, e.g. to oxygen and hydrogen gas. This is their essential function when incorporated into a membrane electrode assembly (MEA) of a proton-exchange membrane fuel cell or of a proton-exchange membrane electrolyser: separation of reactants and transport of protons while blocking a direct electronic pathway through the membrane.

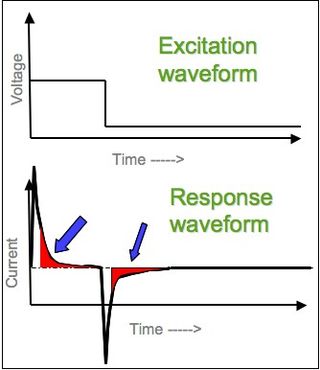

In electrochemistry, chronoamperometry is an analytical technique in which the electric potential of the working electrode is stepped and the resulting current from faradaic processes occurring at the electrode is monitored as a function of time. The functional relationship between current response and time is measured after applying single or double potential step to the working electrode of the electrochemical system. Limited information about the identity of the electrolyzed species can be obtained from the ratio of the peak oxidation current versus the peak reduction current. However, as with all pulsed techniques, chronoamperometry generates high charging currents, which decay exponentially with time as any RC circuit. The Faradaic current - which is due to electron transfer events and is most often the current component of interest - decays as described in the Cottrell equation. In most electrochemical cells, this decay is much slower than the charging decay-cells with no supporting electrolyte are notable exceptions. Most commonly a three-electrode system is used. Since the current is integrated over relatively longer time intervals, chronoamperometry gives a better signal-to-noise ratio in comparison to other amperometric techniques.

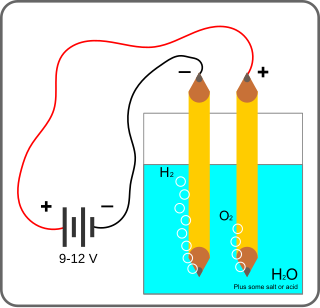

Electrolysis of water is using electricity to split water into oxygen and hydrogen gas by electrolysis. Hydrogen gas released in this way can be used as hydrogen fuel, or remixed with the oxygen to create oxyhydrogen gas, for use in welding and other applications.

In electrochemistry, overpotential is the potential difference (voltage) between a half-reaction's thermodynamically-determined reduction potential and the potential at which the redox event is experimentally observed. The term is directly related to a cell's voltage efficiency. In an electrolytic cell the existence of overpotential implies that the cell requires more energy than thermodynamically expected to drive a reaction. In a galvanic cell the existence of overpotential means less energy is recovered than thermodynamics predicts. In each case the extra/missing energy is lost as heat. The quantity of overpotential is specific to each cell design and varies across cells and operational conditions, even for the same reaction. Overpotential is experimentally determined by measuring the potential at which a given current density is achieved.

A voltameter or coulometer is a scientific instrument used for measuring electric charge through electrolytic action. The SI unit of electric charge is the coulomb.

The Faraday-efficiency effect refers to the potential for misinterpretation of data from experiments in electrochemistry through failure to take into account a Faraday efficiency of less than 100 percent.

The Glossary of fuel cell terms lists the definitions of many terms used within the fuel cell industry. The terms in this fuel cell glossary may be used by fuel cell industry associations, in education material and fuel cell codes and standards to name but a few.

Bulk electrolysis is also known as potentiostatic coulometry or controlled potential coulometry. The experiment is a form of coulometry which generally employs a three electrode system controlled by a potentiostat. In the experiment the working electrode is held at a constant potential (volts) and current (amps) is monitored over time (seconds). In a properly run experiment an analyte is quantitatively converted from its original oxidation state to a new oxidation state, either reduced or oxidized. As the substrate is consumed, the current also decreases, approaching zero when the conversion nears completion.

A solid oxide electrolyzer cell (SOEC) is a solid oxide fuel cell that runs in regenerative mode to achieve the electrolysis of water by using a solid oxide, or ceramic, electrolyte to produce hydrogen gas and oxygen. The production of pure hydrogen is compelling because it is a clean fuel that can be stored, making it a potential alternative to batteries, methane, and other energy sources. Electrolysis is currently the most promising method of hydrogen production from water due to high efficiency of conversion and relatively low required energy input when compared to thermochemical and photocatalytic methods.

An electrocatalyst is a catalyst that participates in electrochemical reactions. Electrocatalysts are a specific form of catalysts that function at electrode surfaces or, most commonly, may be the electrode surface itself. An electrocatalyst can be heterogeneous such as a platinized electrode. Homogeneous electrocatalysts, which are soluble, assist in transferring electrons between the electrode and reactants, and/or facilitate an intermediate chemical transformation described by an overall half reaction. Major challenges in electrocatalysts focus on fuel cells.

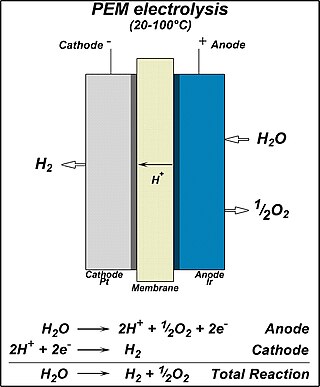

Proton exchange membrane(PEM) electrolysis is the electrolysis of water in a cell equipped with a solid polymer electrolyte (SPE) that is responsible for the conduction of protons, separation of product gases, and electrical insulation of the electrodes. The PEM electrolyzer was introduced to overcome the issues of partial load, low current density, and low pressure operation currently plaguing the alkaline electrolyzer. It involves a proton-exchange membrane.

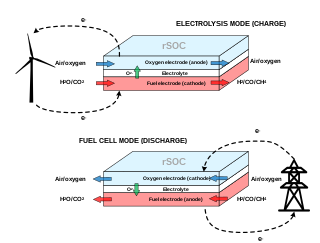

A reversible solid oxide cell (rSOC) is a solid-state electrochemical device that is operated alternatively as a solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC) and a solid oxide electrolysis cell (SOEC). Similarly to SOFCs, rSOCs are made of a dense electrolyte sandwiched between two porous electrodes. Their operating temperature ranges from 600°C to 900°C, hence they benefit from enhanced kinetics of the reactions and increased efficiency with respect to low-temperature electrochemical technologies.

References

- ↑ Bard, A. J.; Faulkner, L. R. (2000). Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-04372-9.

- ↑ Mavrikis, Sotirios; Perry, Samuel C.; Leung, Pui Ki; Wang, Ling; Ponce de León, Carlos (2021-01-11). "Recent Advances in Electrochemical Water Oxidation to Produce Hydrogen Peroxide: A Mechanistic Perspective". ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering. 9 (1): 76–91. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c07263. S2CID 234271584.

- ↑ Jones, J. E.; et al. (1995). "Faradaic efficiencies less than 100% during electrolysis of water can account for reports of excess heat in 'cold fusion' cells". J. Phys. Chem. 99 (18): 6973–6979. doi:10.1021/j100018a033.

- ↑ Shkedi, Z.; et al. (1995). "Calorimetry, Excess Heat, and Faraday Efficiency in Ni-H2O Electrolytic Cells". Fusion Technology. 28 (4): 1720–1731. doi:10.13182/FST95-A30436.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-21. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)