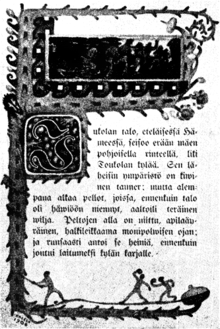

The Kalevala is a 19th-century work of epic poetry compiled by Elias Lönnrot from Karelian and Finnish oral folklore and mythology, telling an epic story about the Creation of the Earth, describing the controversies and retaliatory voyages between the peoples of the land of Kalevala called Väinölä and the land of Pohjola and their various protagonists and antagonists, as well as the construction and robbery of the epic mythical wealth-making machine Sampo.

Aleksis Kivi was a Finnish author who wrote the first significant novel in the Finnish language, Seitsemän veljestä in 1870. He is also known for his 1864 play Heath Cobblers. Although Kivi was among the very earliest authors of prose and lyrics in Finnish, he is still considered one of the greatest.

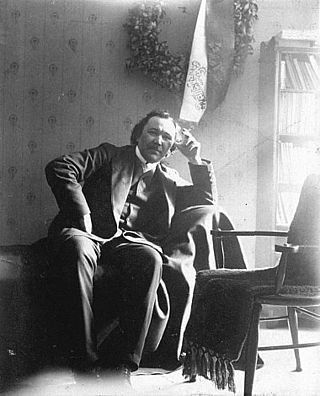

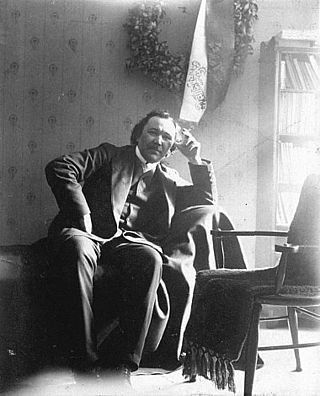

Eino Leino was a Finnish poet and journalist who is considered one of the pioneers of Finnish poetry and a national poet of Finland. His poems combine modern and Finnish folk elements. Much of his work is in the style of the Kalevala and folk songs in general. Nature, love, and despair are frequent themes in Leino's work. He is beloved and widely read in Finland today.

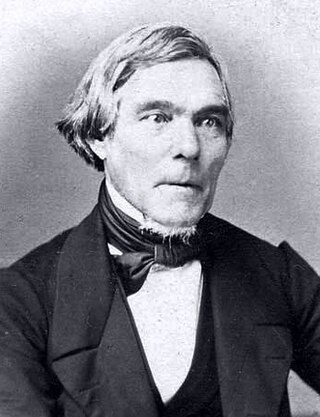

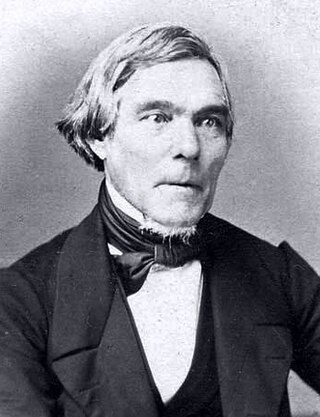

Elias Lönnrot was a Finnish physician, philologist and collector of traditional Finnish oral poetry. He is best known for creating the Finnish national epic, Kalevala, (1835, enlarged 1849), from short ballads and lyric poems gathered from the Finnish oral tradition during several expeditions in Finland, Russian Karelia, the Kola Peninsula and Baltic countries.

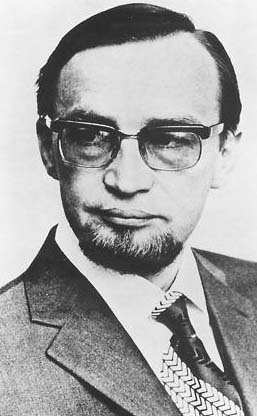

Paavo Juhani Haavikko was a Finnish poet, playwright, essayist and publisher, considered one of the country's most outstanding writers. He published more than 70 works, and his poems have been translated to 12 languages.

Finnish poetry is the poetry from Finland. It is usually written in the Finnish language or Swedish language, but can also include poetry written in Northern Sámi or other Sámi languages. It has its roots in the early folk music of the area, and still has a thriving presence today.

The Finno-Permic (Fenno-Permic) or Finno-Permian (Fenno-Permian) languages, or sometimes just Finnic (Fennic) languages, are a proposed subdivision of the Uralic languages which comprise the Balto-Finnic languages, Sámi languages, Mordvinic languages, Mari language, Permic languages and likely a number of extinct languages. In the traditional taxonomy of the Uralic languages, Finno-Permic is estimated to have split from Finno-Ugric around 3000–2500 BC, and branched into Permic languages and Finno-Volgaic languages around 2000 BC. Nowadays the validity of the group as a taxonomical entity is being questioned, and the interrelationships of its five branches are debated with little consensus.

Scandinavian literature or Nordic literature is the literature in the languages of the Nordic countries of Northern Europe. The Nordic countries include Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and Scandinavia's associated autonomous territories. The majority of these nations and regions use North Germanic languages. Although the majority of Finns speak a Uralic language, Finnish history and literature are clearly interrelated with those of both Sweden and Norway who have shared control of various areas and who have substantial Sami populations/influences.

Jalmari Verneri Sauli was a Finnish writer and track and field athlete who competed in the 1908 Summer Olympics.

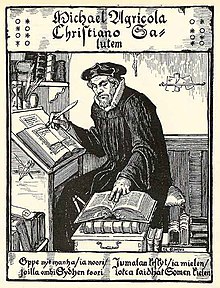

Cristfried Ganander was a Finnish compiler of folk culture, a priest and an 18th-century lexicographer. Ganander's greatest achievement was the compilation of the first fully extensive Finnish-language dictionary which was, however, unpublished. He was also a collector of folk culture well before Elias Lönnrot. His most well-known published work is Mythologia Fennica in 1789, a reference book of folk religion. He also published some poetry and worked as a teacher.

Kanteletar is a collection of Finnish folk poetry compiled by Elias Lönnrot. It is considered to be a sister collection to the Finnish national epic Kalevala. The poems of Kanteletar are based on the trochaic tetrameter, generally referred to as "Kalevala metre".

Carl Axel Gottlund was a Finnish explorer, collector of folklore, historian, cultural politician, linguist, philologist, translator, writer, publisher and lecturer of Finnish language at the University of Helsinki. He was a colorful cultural personality and one of the central Finnish national awakeners and — later — one of the leading dissidents at the same time.

Eeva Elisabeth Joenpelto, married name after 1945 Hellemann, was an award-winning Finnish novelist. Her writing is especially remembered for the Lohja tetralogy which depicted strong women. Described as a "productive novelist of monomaniacal intensity", she occasionally wrote under the pseudonyms of Eeva Helle and Eeva Autere. Joenpelto was President of PEN Finland in 1964-67 and worked as an art professor from 1980–85. She was married to Jarl Hellemann, the CEO of Tammi.

Kalevala Day, known as Finnish Culture Day by its other official name, is celebrated each 28 February in honor of the Finnish national epic, Kalevala. The day is one of the official flag flying days in Finland.

Folklore of Finland refers to traditional and folk practices, technologies, beliefs, knowledge, attitudes and habits in Finland. Finnish folk tradition includes in a broad sense all Finnish traditional folk culture. Folklore is not new, commercial or foreign contemporary culture, or the so-called "high culture". In particular, rural traditions have been considered in Finland as folklore.

Suomen kansan vanhat runot, or SKVR, is an edition of traditional Finnic-language verse containing around 100,000 different songs, and including the majority of the songs that were the sources of the Kalevala and related poetry. The collection is available, free, online.

Synty is an important concept in Finnish mythology. Syntysanat ('origin-words') or syntyloitsut ('origin-charms') provide an explanatory, mythical account of the origin of a phenomenon, material, or species, and were an important part of traditional Finno-Karelian culture, particularly in healing rituals. Although much in the Finnish traditional charms is paralleled elsewhere, 'the role of aetiological and cosmogonic myths' in Finnic tradition 'appears exceptional in Eurasia'. The major study remains that by Kaarle Krohn, published in 1917.

The corpus of traditional riddles from the Finnic-speaking world is fairly unitary, though eastern Finnish-speaking regions show particular influence of Russian Orthodox Christianity and Slavonic riddle culture. The Finnish for 'riddle' is arvoitus, related to the verb arvata and arpa.

Arja Anna-Leena Siikala was a professor emeritus at the University of Helsinki, specialising in folk-belief, mythology, and shamanism, along with oral storytelling and traditionality.

Hannu Pekka Antero Väisänen is a graphic artist, painter and writer from Finland. He now lives in France, and his work has been shown in numerous European countries.