In metalworking and jewelry making, casting is a process in which a liquid metal is delivered into a mold that contains a negative impression of the intended shape. The metal is poured into the mold through a hollow channel called a sprue. The metal and mold are then cooled, and the metal part is extracted. Casting is most often used for making complex shapes that would be difficult or uneconomical to make by other methods.

Zone melting is a group of similar methods of purifying crystals, in which a narrow region of a crystal is melted, and this molten zone is moved along the crystal. The molten region melts impure solid at its forward edge and leaves a wake of purer material solidified behind it as it moves through the ingot. The impurities concentrate in the melt, and are moved to one end of the ingot. Zone refining was invented by John Desmond Bernal and further developed by William G. Pfann in Bell Labs as a method to prepare high-purity materials, mainly semiconductors, for manufacturing transistors. Its first commercial use was in germanium, refined to one atom of impurity per ten billion, but the process can be extended to virtually any solute–solvent system having an appreciable concentration difference between solid and liquid phases at equilibrium. This process is also known as the float zone process, particularly in semiconductor materials processing.

Aluminium–silicon alloys or Silumin is a general name for a group of lightweight, high-strength aluminium alloys based on an aluminum–silicon system (AlSi) that consist predominantly of aluminum - with silicon as the quantitatively most important alloying element. Pure AlSi alloys cannot be hardened, the commonly used alloys AlSiCu and AlSiMg can be hardened. The hardening mechanism corresponds to that of AlCu and AlMgSi.

A riser, also known as a feeder, is a reservoir built into a metal casting mold to prevent cavities due to shrinkage. Most metals are less dense as a liquid than as a solid so castings shrink upon cooling, which can leave a void at the last point to solidify. Risers prevent this by providing molten metal to the casting as it solidifies, so that the cavity forms in the riser and not the casting. Risers are not effective on materials that have a large freezing range, because directional solidification is not possible. They are also not needed for casting processes that utilized pressure to fill the mold cavity.

A dendrite in metallurgy is a characteristic tree-like structure of crystals growing as molten metal solidifies, the shape produced by faster growth along energetically favourable crystallographic directions. This dendritic growth has large consequences in regard to material properties.

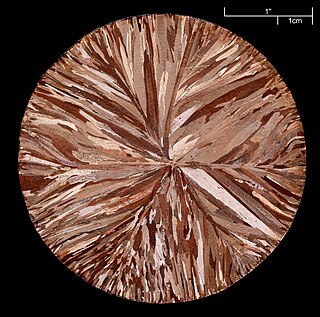

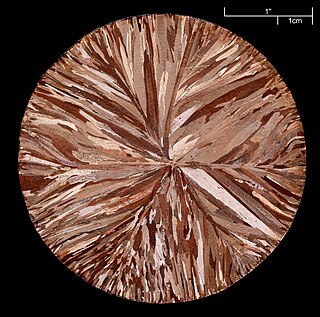

Spin casting, also known as centrifugal rubber mold casting (CRMC), is a method of utilizing inertia to produce castings from a rubber mold. Typically, a disc-shaped mold is spun along its central axis at a set speed. The casting material, usually molten metal or liquid thermoset plastic, is then poured in through an opening at the top-center of the mold. The filled mold then continues to spin as the metal solidifies.

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals processed are aluminum and cast iron. However, other metals, such as bronze, brass, steel, magnesium, and zinc, are also used to produce castings in foundries. In this process, parts of desired shapes and sizes can be formed.

Continuous casting, also called strand casting, is the process whereby molten metal is solidified into a "semifinished" billet, bloom, or slab for subsequent rolling in the finishing mills. Prior to the introduction of continuous casting in the 1950s, steel was poured into stationary molds to form ingots. Since then, "continuous casting" has evolved to achieve improved yield, quality, productivity and cost efficiency. It allows lower-cost production of metal sections with better quality, due to the inherently lower costs of continuous, standardised production of a product, as well as providing increased control over the process through automation. This process is used most frequently to cast steel. Aluminium and copper are also continuously cast.

Investment casting is an industrial process based on lost-wax casting, one of the oldest known metal-forming techniques. The term "lost-wax casting" can also refer to modern investment casting processes.

Spray forming, also known as spray casting, spray deposition and in-situ compaction, is a method of casting near net shape metal components with homogeneous microstructures via the deposition of semi-solid sprayed droplets onto a shaped substrate. In spray forming an alloy is melted, normally in an induction furnace, then the molten metal is slowly poured through a conical tundish into a small-bore ceramic nozzle. The molten metal exits the furnace as a thin free-falling stream and is broken up into droplets by an annular array of gas jets, and these droplets then proceed downwards, accelerated by the gas jets to impact onto a substrate. The process is arranged such that the droplets strike the substrate whilst in the semi-solid condition, this provides sufficient liquid fraction to 'stick' the solid fraction together. Deposition continues, gradually building up a spray formed billet of metal on the substrate.

In casting, a pattern is a replica of the object to be cast, used to form the sand mould cavity into which molten metal is poured during the casting process. Once the pattern has been used to form the sand mould cavity, the pattern is then removed, Molten metal is then poured into the sand mould cavity to produce the casting. The pattern is non consumable and can be reused to produce further sand moulds almost indefinitely.

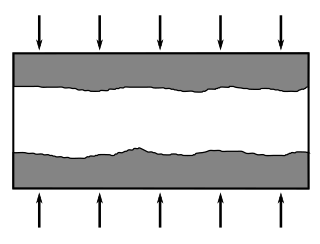

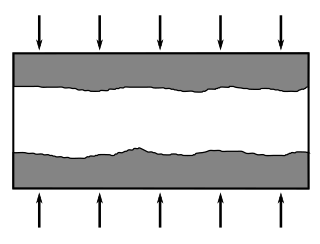

Directional solidification(DS) and progressive solidification are types of solidification within castings. Directional solidification is solidification that occurs from farthest end of the casting and works its way towards the sprue. Progressive solidification, also known as parallel solidification, is solidification that starts at the walls of the casting and progresses perpendicularly from that surface.

Permanent mold casting is a metal casting process that employs reusable molds, usually made from metal. The most common process uses gravity to fill the mold, however gas pressure or a vacuum are also used. A variation on the typical gravity casting process, called slush casting, produces hollow castings. Common casting metals are aluminium, magnesium, and copper alloys. Other materials include tin, zinc, and lead alloys and iron and steel are also cast in graphite molds.

Bismuth bronze or bismuth brass is a copper alloy which typically contains 1-3% bismuth by weight, although some alloys contain over 6% Bi. This bronze alloy is very corrosion-resistant, a property which makes it suitable for use in environments such as the ocean. Bismuth bronzes and brasses are more malleable, thermally conductive, and polish better than regular brasses. The most common industrial application of these metals are as bearings, however the material has been in use since the late nineteenth century as kitchenware and mirrors. Bismuth bronze was also found in ceremonial Inca knives at Machu Picchu. Recently, pressure for the substitution of hazardous metals has increased and with it bismuth bronze is being marketed as a green alternative to leaded bronze bearings and bushings.

Casting is a manufacturing process in which a liquid material is usually poured into a mold, which contains a hollow cavity of the desired shape, and then allowed to solidify. The solidified part is also known as a casting, which is ejected or broken out of the mold to complete the process. Casting materials are usually metals or various time setting materials that cure after mixing two or more components together; examples are epoxy, concrete, plaster and clay. Casting is most often used for making complex shapes that would be otherwise difficult or uneconomical to make by other methods. Heavy equipment like machine tool beds, ships' propellers, etc. can be cast easily in the required size, rather than fabricating by joining several small pieces. Casting is a 7,000-year-old process. The oldest surviving casting is a copper frog from 3200 BC.

A casting defect is an undesired irregularity in a metal casting process. Some defects can be tolerated while others can be repaired, otherwise they must be eliminated. They are broken down into five main categories: gas porosity, shrinkage defects, mould material defects, pouring metal defects, and metallurgical defects.

Centrifugal casting or rotocasting is a casting technique that is typically used to cast thin-walled cylinders. It is typically used to cast materials such as metals, glass, and concrete. A high quality is attainable by control of metallurgy and crystal structure. Unlike most other casting techniques, centrifugal casting is chiefly used to manufacture rotationally symmetric stock materials in standard sizes for further machining, rather than shaped parts tailored to a particular end-use.

An inclusion is a solid particle in liquid aluminium alloy. It is usually non-metallic and can be of different nature depending on its source.

Splat quenching is a metallurgical, metal morphing technique used for forming metals with a particular crystal structure by means of extremely rapid quenching, or cooling.

Direct Chill casting is a method for the fabrication of cylindrical or rectangular solid ingots from non-ferrous metals, especially Aluminum, Copper, Magnesium and their alloys. The original ingots are usually further processed by other methods. More than half of global aluminum production uses the Direct Chill casting process.