Related Research Articles

A pidgin, or pidgin language, is a grammatically simplified means of communication that develops between two or more groups of people that do not have a language in common: typically, its vocabulary and grammar are limited and often drawn from several languages. It is most commonly employed in situations such as trade, or where both groups speak languages different from the language of the country in which they reside. Linguists do not typically consider pidgins as full or complete languages.

A creole language, or simply creole, is a stable natural language that develops from the process of different languages simplifying and mixing into a new form, and then that form expanding and elaborating into a full-fledged language with native speakers, all within a fairly brief period of time. While the concept is similar to that of a mixed or hybrid language, creoles are often characterized by a tendency to systematize their inherited grammar. Like any language, creoles are characterized by a consistent system of grammar, possess large stable vocabularies, and are acquired by children as their native language. These three features distinguish a creole language from a pidgin. Creolistics, or creology, is the study of creole languages and, as such, is a subfield of linguistics. Someone who engages in this study is called a creolist.

A Spanish creole, or Spanish-based creole language, is a creole language for which Spanish serves as its substantial lexifier.

Portuguese creoles are creole languages which have Portuguese as their substantial lexifier. The most widely-spoken creoles influenced by Portuguese are Cape Verdean Creole, Guinea-Bissau Creole and Papiamento.

In linguistics, a stratum or strate is a language that influences or is influenced by another through contact. A substratum or substrate is a language that has lower power or prestige than another, while a superstratum or superstrate is the language that has higher power or prestige. Both substratum and superstratum languages influence each other, but in different ways. An adstratum or adstrate is a language that is in contact with another language in a neighbor population without having identifiably higher or lower prestige. The notion of "strata" was first developed by the Italian linguist Graziadio Isaia Ascoli (1829–1907), and became known in the English-speaking world through the work of two different authors in 1932.

In addition to its classical and literary form, Malay had various regional dialects established after the rise of the Srivijaya empire in Sumatra, Indonesia. Also, Malay spread through interethnic contact and trade across the Malay Archipelago as far as the Philippines. That contact resulted in a lingua franca that was called Bazaar Malay or low Malay and in Malay Melayu Pasar. It is generally believed that Bazaar Malay was a pidgin, influenced by contact among Malay, Hokkien, Portuguese, and Dutch traders.

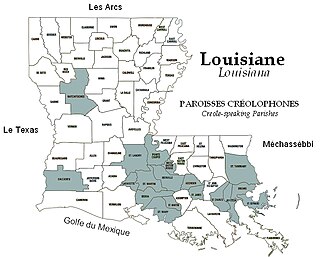

Louisiana Creole is a French-based creole language spoken by fewer than 10,000 people, mostly in the state of Louisiana. Also known as Kouri-Vini, it is spoken today by people who may racially identify as White, Black, mixed, and Native American, as well as Cajun and Creole. It should not be confused with its sister language, Louisiana French, a dialect of the French language. Many Louisiana Creoles do not speak the Louisiana Creole language and may instead use French or English as their everyday languages.

Palenquero or Palenque is a Spanish-based creole language spoken in Colombia. It is believed to be a mixture of Kikongo and Spanish. However, there is no sufficient evidence to indicate that Palenquero is strictly the result of a two-language contact. Palenquero is the only surviving Spanish-based creole language in Latin America, if Papiamento is excluded. Over 6,600 people spoke this language in 2018. It is primarily spoken in the village of San Basilio de Palenque which is southeast of Cartagena, and in some neighbourhoods of Barranquilla.

Nigerian Pidgin, also called Naijá or Naija, is an English-based creole language spoken as a lingua franca across Nigeria. The language is sometimes referred to as "Pijin" or Broken. It can be spoken as a pidgin, a creole, dialect or a decreolised acrolect by different speakers, who may switch between these forms depending on the social setting. In the 2010s, a common orthography was developed for Pidgin which has been gaining significant popularity in giving the language a harmonized writing system.

In linguistics, relexification is a mechanism of language change by which one language changes much or all of its lexicon, including basic vocabulary, with the lexicon of another language, without drastically changing the relexified language's grammar. The term is principally used to describe pidgins, creoles, and mixed languages.

Decreolization is a postulated phenomenon whereby over time a creole language reconverges with the lexifier from which it originally derived. The notion has attracted criticism from linguists who argue there is little theoretical or empirical basis on which to postulate a process of language change which is particular to creole languages.

Berbice Creole Dutch is a now extinct Dutch creole language, once spoken in Berbice, a region along the Berbice River in Guyana. It had a lexicon largely based on Dutch and Eastern Ijo varieties from southern Nigeria. In contrast to the widely known Negerhollands Dutch creole spoken in the Virgin Islands, Berbice Creole Dutch and its relative Skepi Creole Dutch, were more or less unknown to the outside world until Ian Robertson first reported on the two languages in 1975. Dutch linguist Silvia Kouwenberg subsequently investigated the creole language, publishing its grammar in 1994, and numerous other works examining its formation and uses.

An English-based creole language is a creole language for which English was the lexifier, meaning that at the time of its formation the vocabulary of English served as the basis for the majority of the creole's lexicon. Most English creoles were formed in British colonies, following the great expansion of British naval military power and trade in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. The main categories of English-based creoles are Atlantic and Pacific.

A French creole, or French-based creole language, is a creole for which French is the lexifier. Most often this lexifier is not modern French but rather a 17th- or 18th-century koiné of French from Paris, the French Atlantic harbors, and the nascent French colonies. This article also contains information on French pidgin languages, contact languages that lack native speakers.

French Guianese Creole is a French-based creole language spoken in French Guiana, and to a lesser degree, in Suriname and Guyana. It resembles Antillean Creole, but there are some lexical and grammatical differences between them. Antilleans can generally understand French Guianese Creole, though there may be some instances of confusion. The differences consist of more French and Brazilian Portuguese influences. There are also words of Amerindian and African origin. There are French Guianese communities in Suriname and Guyana who continue to speak the language.

Sri Lankan Malay is a creole language spoken in Sri Lanka, formed as a mixture of Sinhala and Shonam, with Malay being the major lexifier. It is traditionally spoken by the Sri Lankan Malays and among some Sinhalese in Hambantota. Today, the number of speakers of the language have dwindled considerably but it has continued to be spoken notably in the Hambantota District of Southern Sri Lanka, which has traditionally been home to many Sri Lankan Malays.

Ghanaian Pidgin English (GhaPE), is a Ghanaian English-lexifier pidgin also known as Pidgin, Broken English, and Kru English. GhaPE is a regional variety of West African Pidgin English spoken in Ghana, predominantly in the southern capital, Accra, and surrounding towns. It is confined to a smaller section of society than other West African creoles, and is more stigmatized, perhaps due to the importance of Twi, an Akan dialect, often spoken as lingua franca. Other languages spoken as lingua franca in Ghana are Standard Ghanaian English (SGE) and Akan. GhaPE cannot be considered a creole as it has no L1 speakers.

Japanese-based creole languages or simply Japanese Creoles are creole languages for which Japanese is the lexifier. This article also contains information on Japanese pidgin languages, contact languages that lack native speakers.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Velupillai, Viveka (2015). Pidgins, Creoles and Mixed Languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 519. ISBN 978-90-272-5272-2.

- ↑ Rachel, Selbach. "2. The superstrate is not always the lexifier: Lingua Franca in the Barbary Coast 1530-1830". Creole Language Library: 29–58.

- ↑ "lexicon, n." . OED Online. Oxford University Press. December 2018. Retrieved 2018-12-29.

- ↑ Gleibermann, Erik (2018). "Inside the Bilingual Writer". World Literature Today. 92 (3): 30–34. doi:10.7588/worllitetoda.92.3.0030. JSTOR 10.7588/worllitetoda.92.3.0030. S2CID 165625005.

- ↑ "Mobile Versus Fixed Bearing Medial Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty: A Series of 375 Patients". doi:10.15438/rr.5.1.28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Nicaragua Creole English". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ↑ "Islander Creole English". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- ↑ "Saint Lucian Creole French". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ↑ "Guianese Creole French".

- ↑ "Haitian Creole". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ↑ "Louisiana Creole". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ↑ "Morisyen".

- ↑ "Réunion Creole French".

- ↑ Kouwenberg, Silvia (2005-01-01). "Marlyse Baptista. 2002. The Syntax of Cape Verdean Creole. The Sotavento Varieties". Studies in Language. 29 (1): 255–259. doi:10.1075/sl.29.1.19kou. ISSN 1569-9978.

- ↑ Koontz-Garboden, Andrew J.; Clements, J. Clancy (2002-01-01). "Two Indo-Portuguese Creoles in contrast". Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages. 17 (2): 191–236. doi:10.1075/jpcl.17.2.03cle. ISSN 1569-9870.

- ↑ Lipski, John M. (2012-04-11). "Remixing a mixed language: The emergence of a new pronominal system in Chabacano (Philippine Creole Spanish)". International Journal of Bilingualism. 17 (4): 448–478. doi:10.1177/1367006912438302. ISSN 1367-0069. S2CID 53459665.

- ↑ Lipski, John M. (2012). "Free at Last: From Bound Morpheme to Discourse Marker in Lengua ri Palenge (Palenquero Creole Spanish)". Anthropological Linguistics. 54 (2): 101–132. doi:10.1353/anl.2012.0007. JSTOR 23621075. S2CID 143540760.

- ↑ Bakker, Peter (September 2014). "Three Dutch Creoles in Comparison". Journal of Germanic Linguistics. 26 (3): 191–222. doi:10.1017/S1470542714000063. ISSN 1475-3014. S2CID 170572846.

- ↑ Zeijlstra, Hedde; Goddard, Denice (2017-03-01). "On Berbice Dutch VO status". Language Sciences. 60: 120–132. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2016.11.001. ISSN 0388-0001.

- ↑ Sanders, Mark (2016-06-09). "Why are you Learning Zulu?". Interventions. 18 (6): 806–815. doi:10.1080/1369801x.2016.1196145. ISSN 1369-801X. S2CID 148247812.