Meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS) also known as neonatal aspiration of meconium is a medical condition affecting newborn infants. It describes the spectrum of disorders and pathophysiology of newborns born in meconium-stained amniotic fluid (MSAF) and have meconium within their lungs. Therefore, MAS has a wide range of severity depending on what conditions and complications develop after parturition. Furthermore, the pathophysiology of MAS is multifactorial and extremely complex which is why it is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in term infants.

A pulmonary alveolus, also known as an air sac or air space, is one of millions of hollow, distensible cup-shaped cavities in the lungs where pulmonary gas exchange takes place. Oxygen is exchanged for carbon dioxide at the blood–air barrier between the alveolar air and the pulmonary capillary. Alveoli make up the functional tissue of the mammalian lungs known as the lung parenchyma, which takes up 90 percent of the total lung volume.

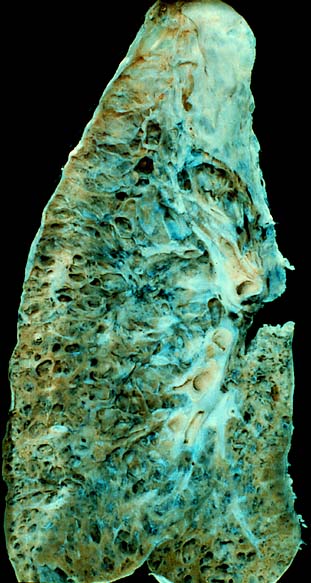

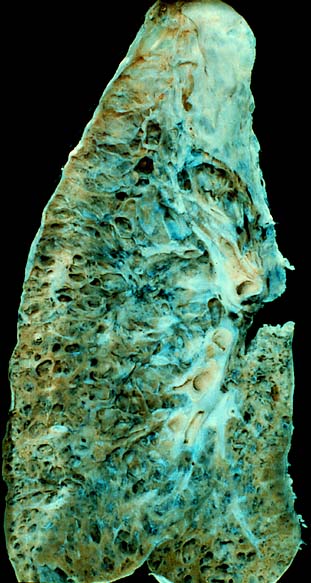

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP) is a rare lung disorder characterized by an abnormal accumulation of surfactant-derived lipoprotein compounds within the alveoli of the lung. The accumulated substances interfere with the normal gas exchange and expansion of the lungs, ultimately leading to difficulty breathing and a predisposition to developing lung infections. The causes of PAP may be grouped into primary, secondary, and congenital causes, although the most common cause is a primary autoimmune condition in an individual.

Interstitial lung disease (ILD), or diffuse parenchymal lung disease (DPLD), is a group of respiratory diseases affecting the interstitium and space around the alveoli of the lungs. It concerns alveolar epithelium, pulmonary capillary endothelium, basement membrane, and perivascular and perilymphatic tissues. It may occur when an injury to the lungs triggers an abnormal healing response. Ordinarily, the body generates just the right amount of tissue to repair damage, but in interstitial lung disease, the repair process is disrupted, and the tissue around the air sacs (alveoli) becomes scarred and thickened. This makes it more difficult for oxygen to pass into the bloodstream. The disease presents itself with the following symptoms: shortness of breath, nonproductive coughing, fatigue, and weight loss, which tend to develop slowly, over several months. The average rate of survival for someone with this disease is between three and five years. The term ILD is used to distinguish these diseases from obstructive airways diseases.

Pulmonary surfactant is a surface-active complex of phospholipids and proteins formed by type II alveolar cells. The proteins and lipids that make up the surfactant have both hydrophilic and hydrophobic regions. By adsorbing to the air-water interface of alveoli, with hydrophilic head groups in the water and the hydrophobic tails facing towards the air, the main lipid component of surfactant, dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC), reduces surface tension.

Pneumonitis describes general inflammation of lung tissue. Possible causative agents include radiation therapy of the chest, exposure to medications used during chemo-therapy, the inhalation of debris, aspiration, herbicides or fluorocarbons and some systemic diseases. If unresolved, continued inflammation can result in irreparable damage such as pulmonary fibrosis.

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP), formerly known as bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP), is an inflammation of the bronchioles (bronchiolitis) and surrounding tissue in the lungs. It is a form of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is a diagnostic method of the lower respiratory system in which a bronchoscope is passed through the mouth or nose into an appropriate airway in the lungs, with a measured amount of fluid introduced and then collected for examination. This method is typically performed to diagnose pathogenic infections of the lower respiratory airways, though it also has been shown to have utility in diagnosing interstitial lung disease. Bronchoalveolar lavage can be a more sensitive method of detection than nasal swabs in respiratory molecular diagnostics, as has been the case with SARS-CoV-2 where bronchoalveolar lavage samples detect copies of viral RNA after negative nasal swab testing.

Lipoid pneumonia is a specific form of lung inflammation (pneumonia) that develops when lipids enter the bronchial tree. The disorder is sometimes called cholesterol pneumonia in cases where that lipid is a factor.

Alveolar lung diseases, are a group of diseases that mainly affect the alveoli of the lungs.

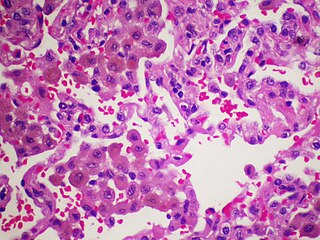

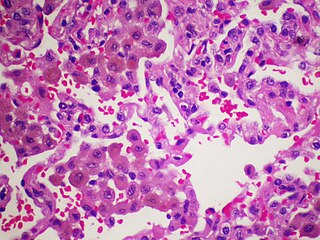

Foam cells, also called lipid-laden macrophages, are a type of cell that contain cholesterol. These can form a plaque that can lead to atherosclerosis and trigger myocardial infarction and stroke.

Exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage (EIPH), also known as "bleeding" or a "bleeding attack", refers to the presence of blood in the airways of the lung in association with exercise. EIPH is common in horses undertaking intense exercise, but it has also been reported in human athletes, racing camels and racing greyhounds. Horses that experience EIPH may also be referred to as "bleeders" or as having "broken a blood vessel". In the majority of cases, EIPH is not apparent unless an endoscopic examination of the airways is performed following exercise. This is distinguished from other forms of bleeding from the nostrils, called epistaxis.

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP) is a form of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia featuring elevated numbers of macrophages within the alveoli of the lung. The alveolar macrophages have a characteristic light brown pigmentation and accumulate in the alveolar lumen and septa regions of the lower lobes of the lungs. The typical effects of the macrophage accumulation are inflammation and later fibrosis of the lung tissue.

Fire breather's pneumonia is a distinct type of exogenous—that is, originating outside the body—lipoid pneumonia that results from inhalation or aspiration of hydrocarbons of different types, such as lamp oil. Accidental inhalation of hydrocarbon fuels can occur during fire breathing, fire eating, or other fire performance, and may lead to pneumonitis.

Indium lung is a rare occupational lung disease caused by exposure to respirable indium in the form of indium tin oxide. It is classified as an interstitial lung disease.

William N. Rom is the Sol and Judith Bergstein Professor of Medicine and Environmental Medicine, Emeritus at New York University School of Medicine and former Director of the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine at New York University and Chief of the Chest Service at Bellevue Hospital Center, 1989–2014. He is Research Scientist at the School of Global Public Health at New York University and Adjunct Professor at the NYU Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service. He teaches Climate Change and Global Public Health and Environmental Health in a Global World.

Vaping-associated pulmonary injury (VAPI), also known as vaping-associated lung injury (VALI) or e-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury (E/VALI), is an umbrella term, used to describe lung diseases associated with the use of vaping products that can be severe and life-threatening. Symptoms can initially mimic common pulmonary diagnoses, such as pneumonia, but sufferers typically do not respond to antibiotic therapy. Differential diagnoses have overlapping features with VAPI, including COVID-19. According to an article in the Radiological Society of North America news published in March 2022, EVALI cases continue to be diagnosed. “EVALI has by no means disappeared,” Dr. Kligerman said. “We continue to see numerous cases, even during the pandemic, many of which are initially misdiagnosed as COVID-19.”

Crazy paving refers to a pattern seen on computed tomography of the chest, involving lobular septal thickening with variable alveolar filling. The finding is seen in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, and other diseases. Its name comes from its resemblance to irregular paving stones, called crazy pavings.

Bat wing appearance is a radiologic sign referring to bilateral perihilar lung shadowing seen in frontal chest X-ray and in chest CT. The most common reason for bat wing appearance is the accumulation of oedema fluid in the lungs. The batwing sign is symmetrical, usually showing ground glass appearance and spares the lung cortices. This sign is seen in individuals with pneumonia, inhalation injuries, pulmonary haemorrhage, sarcoidosis, bronchoalveolar carcinoma and pulmonary alveolar proteinosis.

Smoker’s macrophages are alveolar macrophages whose characteristics, including appearance, cellularity, phenotypes, immune response, and other functions, have been affected upon the exposure to cigarettes. These altered immune cells are derived from several signaling pathways and are able to induce numerous respiratory diseases. They are involved in asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD), pulmonary fibrosis, and lung cancer. Smoker’s macrophages are observed in both firsthand and secondhand smokers, so anyone exposed to cigarette contents, or cigarette smoke extract (CSE), would be susceptible to these macrophages, thus in turns leading to future complications.