The Lugbara live in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda , and South Sudan. Their number totaled approximately 240,000, with around 180,000 residing in north-western Uganda, with the remaining population spread across bordering areas of the modern-day Democratic Republic of Congo and South Sudan. The Lugbara people speak in a Sudanese language. The basic social and economic unit found in Lugbara culture is a lineage group under the authority of a male genealogical elder called ba wara, meaning "big man". These lineage groups, often referred to as sub-tribes, typically lived in a village built atop a hillside or ridge. In addition to the male elder, other religious leaders include diviners, oracles, and rain men.

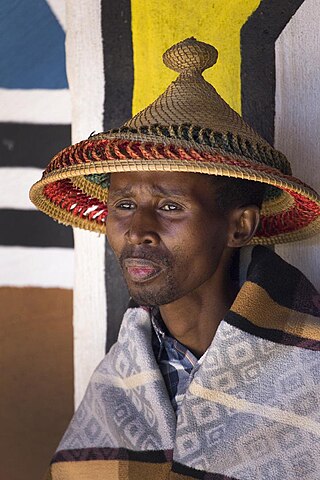

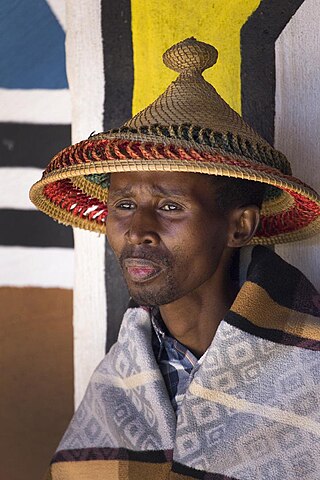

Initiation is a rite of passage marking entrance or acceptance into a group or society. It could also be a formal admission to adulthood in a community or one of its formal components. In an extended sense, it can also signify a transformation in which the initiate is 'reborn' into a new role. Examples of initiation ceremonies might include Christian baptism or confirmation, Jewish bar or bat mitzvah, acceptance into a fraternal organization, secret society or religious order, or graduation from school or recruit training. A person taking the initiation ceremony in traditional rites, such as those depicted in these pictures, is called an initiate.

A rite of passage is a ceremony or ritual of the passage which occurs when an individual leaves one group to enter another. It involves a significant change of status in society. In cultural anthropology the term is the Anglicisation of rite de passage, a French term innovated by the ethnographer Arnold van Gennep in his work Les rites de passage, The Rites of Passage. The term is now fully adopted into anthropology as well as into the literature and popular cultures of many modern languages.

The Dogon are an ethnic group indigenous to the central plateau region of Mali, in West Africa, south of the Niger bend, near the city of Bandiagara, and in Burkina Faso. The population numbers between 400,000 and 800,000. They speak the Dogon languages, which are considered to constitute an independent branch of the Niger–Congo language family, meaning that they are not closely related to any other languages.

The Bambara are a Mandé ethnic group native to much of West Africa, primarily southern Mali, Ghana, Guinea, Burkina Faso and Senegal. They have been associated with the historic Bambara Empire. Today, they make up the largest Mandé ethnic group in Mali, with 80% of the population speaking the Bambara language, regardless of ethnicity.

Candomblé is an African diasporic religion that developed in Brazil during the 19th century. It arose through a process of syncretism between several of the traditional religions of West Africa, especially those of the Yoruba, Bantu, and Gbe, coupled with influences from the Roman Catholic form of Christianity. There is no central authority in control of Candomblé, which is organized around autonomous terreiros (houses).

A jengu is a water spirit in the traditional beliefs of the Sawabantu groups of Cameroon, like the Duala, Bakweri, Malimba, Subu, Bakoko, Oroko people. Among the Bakweri, the term used is liengu. Miengu are similar to bisimbi in the Bakongo spirituality and Mami Wata. The Bakoko people use the term Bisima.

The Chokwe people, known by many other names, are a Bantu ethnic group of Central and Southern Africa. They are found primarily in Angola, southwestern parts of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and northwestern parts of Zambia.

A manbo is a priestess in the Haitian Vodou religion. Haitian Vodou's conceptions of priesthood stem from the religious traditions of enslaved people from Dahomey, in what is today Benin. For instance, the term manbo derives from the Fon word nanbo. Like their West African counterparts, Haitian manbos are female leaders in Vodou temples who perform healing work and guide others during complex rituals. This form of female leadership is prevalent in urban centers such as Port-au-Prince. Typically, there is no hierarchy among manbos and oungans. These priestesses and priests serve as the heads of autonomous religious groups and exert their authority over the devotees or spiritual servants in their hounfo (temples).

The Mongo people are an ethnic group who live in the equatorial forest of Central Africa. They are the largest ethnic group in the Democratic Republic of Congo, highly influential in its north region. The Mongo people are a diverse collection of sub-ethnic groups who are referred to as AnaMongo. The Mongo (Anamongo) subgroups include the Mongo, Batetela, Bakusu, Ekonda, Bolia, Nkundo, Lokele, Topoke, Iyadjima, Ngando, Ndengese, Sengele, Sakata, Mpama, Ntomba, Mbole. The Mongo (Anamongo) occupy 14 provinces particularly the province of Equateur,Tshopo, Tshuapa, Mongala, Kwilu, in Maï Ndombe, Kongo-Centrale, in Kasai, in Sankuru, Maniema, North Kivu and South Kivu, Tanganiyka (Katanga) and Ituri province. Their highest presence is in the province of Équateur and the northern parts of the Bandundu Province(Maï Ndombe).

The Songye people, sometimes written Songe, are a Bantu ethnic group from the central Democratic Republic of the Congo. They speak the Songe language. They inhabit a vast territory between the Sankuru/Lulibash river in the west and the Lualaba River in the east. Many Songye villages can be found in present-day East Kasai province, parts of Katanga and Kivu Province. The people of Songye are divided into thirty-four conglomerate societies; each society is led by a single chief with a Judiciary Council of elders and nobles (bilolo). Smaller kingdoms east of the Lomami River refer to themselves as Songye, other kingdoms in the west, refer to themselves as Kalebwe, Eki, Ilande, Bala, Chofwe, Sanga and Tempa. As a society, the people of Songye are mainly known as a farming community; they do, however, take part in hunting and trading with other neighboring communities.

The Chamba are a significant ethnic group in the north eastern Nigeria. The Chamba are located between present day Nigeria and Cameroon. The closest Chamba neighbours are the Mumuye, the Jukun and Kutep people. In Cameroon, the successors of Leko and chamba speakers are divided into several states: Bali Nyonga, Bali Kumbat, Bali-Gham, Bali-Gangsin, and Bali-Gashu. They are two ethnic groups in Ghana and Togo also called Chamba, but they are ethnically distinct. The Chamba are identified through their own language, beliefs, culture, and art.

Santería, also known as Regla de Ocha, Regla Lucumí, or Lucumí, is an Afro-Caribbean religion that developed in Cuba during the late 19th century. It arose amid a process of syncretism between the traditional Yoruba religion of West Africa, the Roman Catholic form of Christianity, and Spiritism. There is no central authority in control of Santería and much diversity exists among practitioners, who are known as creyentes ("believers").

The Wauja or Waura are an indigenous people of Brazil. Their language, Waurá, is an Arawakan language. They live in the region near the Upper Xingu River, in the Xingu Indigenous Park in the state of Mato Grosso, and had a population of 487 in 2010.

The Saafi people, also called Serer-Safene, Safene, etc., are an ethnic group found in Senegal. Ethnically, they are part of the Serer people but do not speak the Serer language nor a dialect of it. Their language Saafi is classed as one of the Cangin languages. In Senegal, they occupy Dakar and the Thies Region.

Kuba art comprises a diverse array of media, much of which was created for the courts of chiefs and kings of the Kuba Kingdom. Such work often featured decorations, incorporating cowrie shells and animal skins as symbols of wealth, prestige and power. Masks are also important to the Kuba. They are used both in the rituals of the court and in the initiation of boys into adulthood, as well as at funerals. The Kuba produce embroidered raffia textiles which in the past was made for adornment, woven currency, or as tributary goods for funerals and other seminal occasions. The wealth and power of the court system allowed the Kuba to develop a class of professional artisans who worked primarily for the courts but also produced objects of high quality for other individuals of high status.

The Bushong Kuba are responsible for some of the most beautiful and sophisticated masquerade or dance traditions in Africa.

The art of Burkina Faso is the product of a rich cultural history. In part, this is because so few people from Burkina have become Muslim or Christian. Many of the ancient artistic traditions for which Africa is so well known have been preserved in Burkina Faso because so many people continue to honor the ancestral spirits, and the spirits of nature. In great part they honor the spirits through the use of masks and carved figures. Many of the countries to the north of Burkina Faso had become predominantly Muslim, while many of the countries to the south of Burkina Faso are heavily Christian. In contrast many of the people of Burkina Faso continue to offer prayers and sacrifices to the spirits of nature and to the spirits of their ancestors. The result is that they continue to use the sorts of art that we see in museums in Europe and America.

Lebollo la banna is a Sesotho term for male initiation.

A sexual rite of passage is a ceremonial event that marks the passage of a young person to sexual maturity and adulthood, or a widow from the married state to widowhood, and involves some form of sexual activity.