Burleigh Arland Grimes was an American professional baseball player and manager, and the last pitcher officially permitted to throw the spitball. Grimes made the most of this advantage, as well as his unshaven, menacing presence on the mound, which earned him the nickname "Ol' Stubblebeard." He won 270 MLB games, pitched in four World Series over the course of his 19-year career, and was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1964. A decade earlier, he had been inducted into the Wisconsin Athletic Hall of Fame.

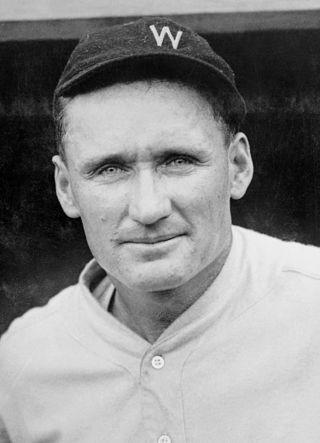

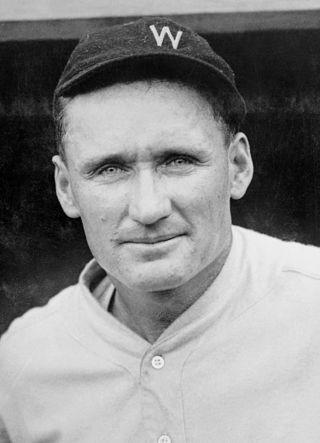

Walter Perry Johnson, nicknamed "Barney" and "the Big Train", was an American professional baseball player and manager. He played his entire 21-year baseball career in Major League Baseball as a right-handed pitcher for the Washington Senators from 1907 to 1927. He later served as manager of the Senators from 1929 through 1932 and of the Cleveland Indians from 1933 through 1935.

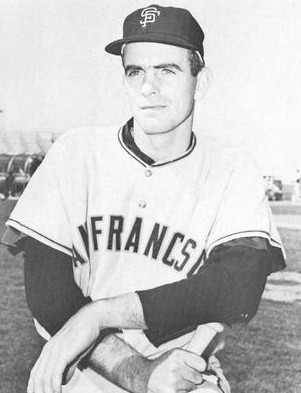

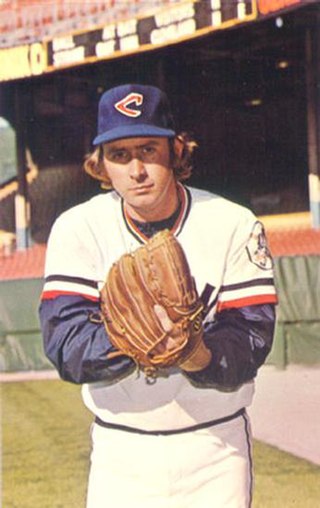

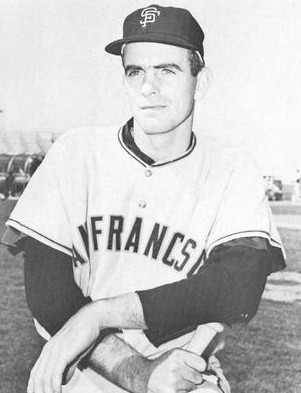

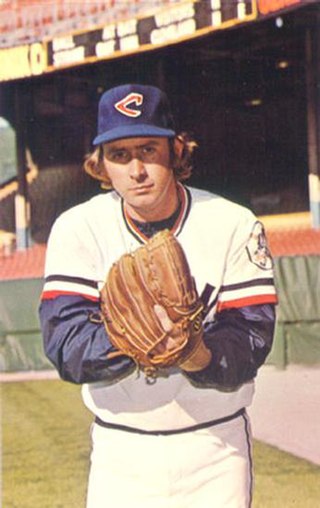

Gaylord Jackson Perry was an American right-handed pitcher in Major League Baseball (MLB) who played for eight teams from 1962 to 1983, becoming one of the most durable and successful pitchers in history. A five-time All-Star, Perry was the first pitcher to win the Cy Young Award in both leagues. He won the American League (AL) award in 1972 after leading the league with 24 wins with a 1.92 earned run average (ERA) for the fifth-place Cleveland Indians, and took the National League (NL) award in 1978 with the San Diego Padres after again leading the league with 21 wins; his Cy Young Award announcement just as he turned the age of 40 made him the oldest to win the award, which stood as a record for 26 years. He and his older brother Jim Perry, who were Cleveland teammates in 1974–1975, became the first brothers to both win 200 games in the major leagues, and remain the only brothers to both win Cy Young Awards.

Michael Stephen Lolich is an American former professional baseball player. He played in Major League Baseball as a left-handed pitcher from 1963 until 1979, almost entirely for the Detroit Tigers. A three-time All-Star, Lolich is most notable for his performance in the 1968 World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals when he earned three complete-game victories, including a win over Bob Gibson in the climactic Game 7. At the time of his retirement in 1979, Lolich held the Major League Baseball record for career strikeouts by a left-handed pitcher.

A spitball is an illegal baseball pitch in which the ball has been altered by the application of a foreign substance such as saliva or petroleum jelly. This technique alters the wind resistance and weight on one side of the ball, causing it to move in an atypical manner. It may also cause the ball to "slip" out of the pitcher's fingers without the usual spin that accompanies a pitch. In this sense, a spitball can be thought of as a fastball with knuckleball action. Alternative names for the spitball are spitter, mud ball, shine ball, supersinker, or vaseline ball. A spitball technically differs from an emery ball, in which the surface of the ball is cut or abraded. Saliva or Vaseline smooths the baseball, while the emery paper roughens it. The general term for altering the ball in any way is doctoring.

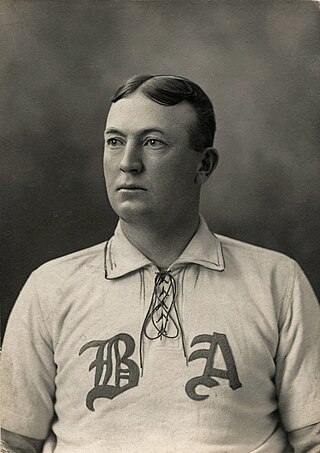

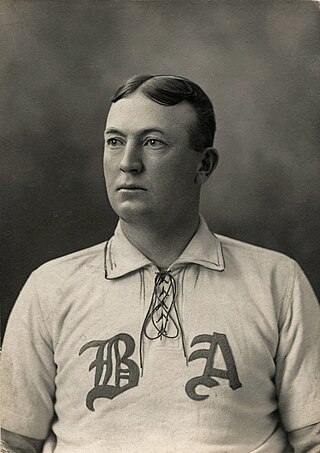

John Dwight Chesbro was an American professional baseball pitcher. Nicknamed "Happy Jack", Chesbro played for the Pittsburgh Pirates (1899–1902), the New York Highlanders (1903–1909), and the Boston Red Sox (1909) of Major League Baseball (MLB). Chesbro finished his career with a 198–132 win–loss record, a 2.68 earned run average, and 1,265 strikeouts. His 41 wins during the 1904 season remains an American League record. Though some pitchers have won more games in some seasons prior to 1901, historians demarcating 1901 as the beginning of 'modern-era' major league baseball refer to and credit Jack Chesbro and his 1904 win-total as the modern era major league record and its holder. Some view Chesbro's 41 wins in a season as an unbreakable record.

In Major League Baseball, the 300-win club is the group of pitchers who have won 300 or more games. Twenty-four pitchers have reached this milestone. This list does not include Bobby Mathews who won 297 in the major leagues plus several more in 1869 and 1870 before the major leagues were established in 1871. The San Francisco Giants are the only franchise to see four players reach 300 wins while on their roster: Tim Keefe in the Players' League, Christy Mathewson and Mickey Welch while the team was in New York, and most recently Randy Johnson. Early in the history of professional baseball, many of the rules favored the pitcher over the batter; the distance pitchers threw to home plate was shorter than today, and pitchers were able to use foreign substances to alter the direction of the ball. Moreover, pitchers started games far more frequently than modern pitchers do; in the second half of the 1884 season Old Hoss Radbourn started every other game. The first player to win 300 games was Pud Galvin in 1888. Seven pitchers recorded all or the majority of their career wins in the 19th century: Galvin, Cy Young, Kid Nichols, Keefe, John Clarkson, Charles Radbourn, and Welch. Four more pitchers joined the club in the first quarter of the 20th century: Mathewson, Walter Johnson, Eddie Plank, and Grover Cleveland Alexander. Young is the all-time leader in wins with 511, a mark that is considered unbreakable. If a modern-day pitcher won 20 games per season for 25 seasons, he would still be 11 games short of Young's mark.

Richard Allen Bosman is an American former professional baseball pitcher. He played in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the Washington Senators / Texas Rangers (1966–73), Cleveland Indians (1973–75), and Oakland Athletics (1975–76). Bosman started the final game for the expansion Senators and the first game for the Texas Rangers. He is the only pitcher in Major League history to miss a perfect game due to his own fielding error.

Robert John Shaw was an American professional baseball player. A right-handed pitcher, he played in Major League Baseball on seven teams for 11 seasons, from 1957 to 1967. In 1962, he was a National League (NL) All-Star player. In 1966, he led all National League pitchers with a perfect 1.000 fielding percentage.

James Evan Perry Jr. is an American former professional baseball pitcher. He pitched in Major League Baseball (MLB) from 1959 to 1975 for the Cleveland Indians, Minnesota Twins, Detroit Tigers, and Oakland Athletics. During a 17-year baseball career, Perry compiled 215 wins, 1,576 strikeouts, and a 3.45 earned run average. He won the Cy Young Award in 1970 and was a three-time MLB All-Star. He and his younger brother Gaylord Perry, who were Cleveland teammates in 1974–1975, became the first brothers to both win 200 games in the major leagues, and remain the only brothers to both win Cy Young Awards.

In baseball, a quality start (QS) is a statistic for a starting pitcher defined as a game in which the pitcher completes at least six innings and permits no more than three earned runs. The quality start was developed by sportswriter John Lowe in 1985 while writing for The Philadelphia Inquirer. He wrote that it "shows exactly how many times a baseball pitcher has done his job."

Michael Grant Marshall was an American professional baseball pitcher. He played in Major League Baseball (MLB) in 1967 and from 1969 through 1981 for nine different teams. Marshall won the National League Cy Young Award in 1974 as a Los Angeles Dodger and was a two-time All-Star selection. He was the first relief pitcher to receive the Cy Young Award.

Michael Richard Waits is an American former professional baseball pitcher. Waits, who threw left-handed, played all or part of twelve seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the Texas Rangers (1973), Cleveland Indians (1975–83), and Milwaukee Brewers (1983–85). Waits served as minor league pitching coordinator for the Seattle Mariners organization before being named pitching coach for the Mariners under new manager Lloyd McClendon for the 2014 season.

The 1974 Cleveland Indians season was the team's 74th season in Major League Baseball. It involved the Indians competing in the American League East, where they finished fourth with a record of 77–85.

The 1968 Major League Baseball season was contested from April 10 to October 10, 1968. It was the final year of baseball's pre-expansion era, in which the teams that finished in first place in each league went directly to the World Series to face each other for the "World Championship."

The 1974 Major League Baseball All-Star Game was the 45th playing of the midsummer classic between the all-stars of the American League (AL) and National League (NL), the two leagues comprising Major League Baseball. The game was held on July 23, 1974, at Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania the home of the Pittsburgh Pirates of the National League. The game resulted in the National League defeating the American League 7–2.

Corey Scott Kluber is an American former professional baseball pitcher. He played in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the Cleveland Indians, Texas Rangers, New York Yankees, Tampa Bay Rays and Boston Red Sox. He made his MLB debut in 2011 as a member of the Indians. A power pitcher, Kluber achieved high strikeout rates through a two-seam sinker and a breaking ball that variously resembled a slider and a curveball.

An emery ball is an illegal pitch in baseball, in which the ball has been altered by scuffing it with a rough surface, such as an emery board or sandpaper. This technique alters the spin of the ball, causing it to move in an atypical manner, as more spin makes the ball rise, while less spin makes the ball drop. The general term for altering the ball in any way is doctoring. The emery ball differs from the spitball, in which the ball is doctored by applying saliva or Vaseline. Vaseline or saliva smooths the baseball, while the emery paper roughens it.

Baseball personnel have cheated by deliberately violating or circumventing the game's rules to gain an unfair advantage against an opponent. Examples of cheating include doctoring the ball, doctoring bats, electronic sign stealing, and the use of performance-enhancing substances. Other actions, such as fielders attempting to mislead baserunners about the location of the ball, are considered gamesmanship and are not in violation of the rules.

The 2021 pitch doctoring controversy arose in Major League Baseball (MLB) around pitchers' use of foreign substances, such as the resin-based Spider Tack, to improve their grip on the baseball and the spin rate on their pitches. On June 15, 2021, MLB announced a new policy whereby any player caught using foreign substances on baseballs would receive a 10-game suspension. The policy also included umpire inspections of all pitchers during games starting on June 21, a decision that was met with mixed reactions from players and coaches.