Burleigh Arland Grimes was an American professional baseball player and manager, and the last pitcher officially permitted to throw the spitball. Grimes made the most of this advantage, as well as his unshaven, menacing presence on the mound, which earned him the nickname "Ol' Stubblebeard." He won 270 MLB games, pitched in four World Series over the course of his 19-year career, and was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1964. A decade earlier, he had been inducted into the Wisconsin Athletic Hall of Fame.

Sanford Koufax is an American former left-handed pitcher in Major League Baseball (MLB) who played his entire career for the Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers from 1955 to 1966. He has been hailed as one of the greatest pitchers in baseball history. After joining the major leagues at age 19, having never pitched a game in the minor leagues, the first half of his career was unremarkable, posting a record of just 36–40 with a 4.10 earned run average (ERA); he was a member of World Series champions in both Brooklyn and Los Angeles, though he did not appear in any of the team's Series wins. But after making adjustments prior to the 1961 season, and benefitting from the team's move into expansive Dodger Stadium a year later, Koufax quickly rose to become the most dominant pitcher in the major leagues before arthritis in his left elbow ended his playing days prematurely at age 30.

A knuckleball or knuckler is a baseball pitch thrown to minimize the spin of the ball in flight, causing an erratic, unpredictable motion. The air flow over a seam of the ball causes the ball to change from laminar to turbulent flow. This change adds a deflecting force to the baseball, making it difficult for batters to hit but also difficult for pitchers to control and catchers to catch; umpires are challenged as well, as the ball's irregular motion through the air makes it harder to call balls and strikes. A pitcher who throws knuckleballs is known as a knuckleballer.

Donald Scott Drysdale was an American professional baseball player and television sports commentator. A right-handed pitcher for the Brooklyn / Los Angeles Dodgers for his entire career in Major League Baseball, Drysdale was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1984.

A split-finger fastball or splitter is an off-speed pitch in baseball that looks to the batter like a fastball until it drops suddenly. Derived from the forkball, it is so named because the pitcher puts the index and middle finger on different sides of the ball.

In baseball, the pitch is the act of throwing the baseball toward home plate to start a play. The term comes from the Knickerbocker Rules. Originally, the ball had to be thrown underhand, much like "pitching in horseshoes". Overhand pitching was not allowed in baseball until 1884.

Urban Clarence "Red" Faber was an American right-handed pitcher in Major League Baseball from 1914 through 1933, playing his entire career for the Chicago White Sox. He was a member of the 1919 team but was not involved in the Black Sox scandal. In fact, he missed the World Series due to injury and illness.

Theodore Amar Lyons was an American professional baseball starting pitcher, manager and coach in Major League Baseball (MLB). He played in 21 MLB seasons, all with the Chicago White Sox. He is the franchise leader in wins. Lyons won 20 or more games three times and became a fan favorite in Chicago.

In baseball, an off-speed pitch is a pitch thrown at a slower speed than a fastball. Breaking balls and changeups are the two most common types of off-speed pitches. Very slow pitches which require the batter to provide most of the power on contact through bat speed are known as "junk" and include the knuckleball and the Eephus pitch, a sort of extreme changeup. The specific goals of off-speed pitches may vary, but in general they are used to disrupt the batter's timing, thereby lessening his chances of hitting the ball solidly or at all. Virtually all professional pitchers have at least one off-speed pitch in their repertoire. Despite the fact that most of these pitches break in some way, batters are sometimes able to anticipate them due to hints that the pitcher gives, such as changes in arm angle, arm speed, or placement of fingers.

Selva Lewis Burdette, Jr. was an American right-handed starting pitcher in Major League Baseball who played primarily for the Boston / Milwaukee Braves. The team's top right-hander during its years in Milwaukee, he was the Most Valuable Player of the 1957 World Series, leading the franchise to its first championship in 43 years, and the only title in Milwaukee history. An outstanding control pitcher, his career average of 1.84 walks per nine innings pitched places him behind only Robin Roberts (1.73), Greg Maddux (1.80), Carl Hubbell, (1.82) and Juan Marichal (1.82) among pitchers with at least 3,000 innings since 1920.

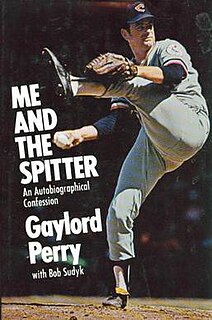

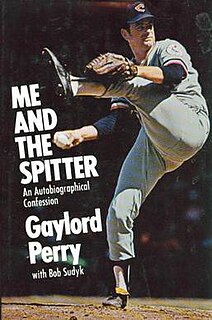

Me and the Spitter: An Autobiographical Confession is a 1974 autobiography by Major League Baseball (MLB) pitcher Gaylord Perry, written with Bob Sudyk, a sportswriter for the Cleveland Press. The book details how Perry cheated at baseball by doctoring the ball.

Urbain Jacques Shockcor, known as Urban James Shocker, was an American professional baseball pitcher. He played in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the New York Yankees and St. Louis Browns between 1916 and 1928.

Elwin Charles Roe, known as Preacher Roe, was an American professional baseball pitcher. He played in Major League Baseball for the St. Louis Cardinals (1938), Pittsburgh Pirates (1944–47), and Brooklyn Dodgers (1948–54). Roe was a five-time All-Star.

William Leopold Doak was an American Major League Baseball pitcher who played for three teams between 1912 and 1929. He spent portions of 13 seasons with the St. Louis Cardinals. He was nicknamed "Spittin' Bill" because he threw the spitball. He led the National League in earned run average in 1914, and he won 20 games in the 1920 season.

The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (ISBN 0-7432-6158-5) is a non-fiction baseball reference book, written by Rob Neyer and Bill James and published by Simon & Schuster in June 2004. In the text on its dust jacket, it bills itself as a "comprehensive guide" to "pitchers, the pitches they throw, and how they throw them".

Frank Victor Shellenback was an American pitcher, pitching coach, and scout in Major League Baseball. As a pitcher, he was famous as an expert spitballer when the pitch was still legal in organized baseball; however, because Shellenback, then 21, was on a minor league roster when the spitball was outlawed after the 1919 season, he was banned from throwing the pitch in the Major Leagues. As a result, Shellenback spent 19 years (1920–38) — the remainder of his active career — throwing the spitball legally in the Pacific Coast League. He won a record 296 PCL games.

The 12–6 curveball is one of the types of pitches thrown in baseball. It is categorized as a breaking ball because of its downward break. The 12–6 curveball, unlike the normal curveball, breaks in a downward motion in a straight line. This explains the name "12–6", because the break of the pitch refers to the ball breaking from the number 12 to the number 6 on a clock. While the 11–5 and 2–8 variations are very effective pitches, they are less effective than a true 12–6, because the ball will break into the heart of the bat more readily.

An emery ball is an illegal pitch in baseball, in which the ball has been altered by scuffing it with a rough surface, such as an emery board or sandpaper. This technique alters the spin of the ball, causing it to move in an atypical manner, as more spin makes the ball rise, while less spin makes the ball drop. The general term for altering the ball in any way is doctoring. The emery ball differs from the spitball, in which the ball is doctored by applying saliva or vaseline. Vaseline or saliva smooths the baseball, while the emery paper roughens it.

Cheating in baseball is a deliberate violation of the baseball rules or other behavior that is designed to gain an unfair advantage against an opponent. Forms of cheating include doctoring the baseball, doctoring baseball bats, electronic sign stealing, and the use of performance-enhancing substances. Other actions, such as fielders attempting to mislead baserunners about the location of the ball, are considered gamesmanship and are not in violation of the rules.