Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) are business transactions in which the ownership of companies, business organizations, or their operating units are transferred to or consolidated with another company or business organization. As an aspect of strategic management, M&A can allow enterprises to grow or downsize, and change the nature of their business or competitive position.

The Herfindahl index is a measure of the size of firms in relation to the industry they are in and is an indicator of the amount of competition among them. Named after economists Orris C. Herfindahl and Albert O. Hirschman, it is an economic concept widely applied in competition law, antitrust regulation, and technology management. HHI has continued to be used by antitrust authorities, primarily to evaluate and understand how mergers will affect their associated markets. HHI is calculated by squaring the market share of each competing firm in the industry and then summing the resulting numbers. The result is proportional to the average market share, weighted by market share. As such, it can range from 0 to 1.0, moving from a huge number of very small firms to a single monopolistic producer. Increases in the HHI generally indicate a decrease in competition and an increase of market power, whereas decreases indicate the opposite. Alternatively, the index can be expressed per 10,000 "points". For example, an index of .25 is the same as 2,500 points.

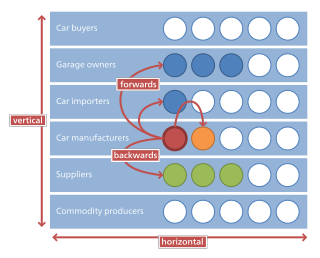

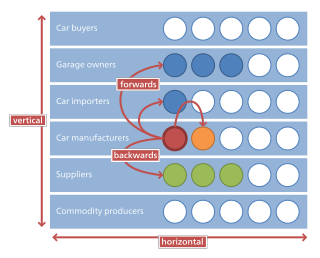

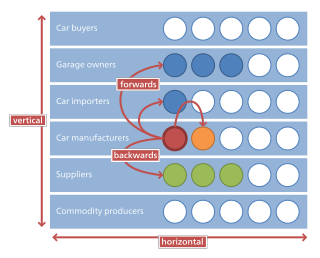

Horizontal integration is the process of a company increasing production of goods or services at the same level of the value chain, in the same industry. A company may do this via internal expansion, acquisition or merger.

In microeconomics, management and international political economy, vertical integration is an arrangement in which the supply chain of a company is integrated and owned by that company. Usually each member of the supply chain produces a different product or (market-specific) service, and the products combine to satisfy a common need. It contrasts with horizontal integration, wherein a company produces several items that are related to one another. Vertical integration has also described management styles that bring large portions of the supply chain not only under a common ownership but also into one corporation.

Anti-competitive practices are business or government practices that prevent or reduce competition in a market. Antitrust laws ensure businesses do not engage in competitive practices that harm other, usually smaller, businesses or consumers. These laws are formed to promote healthy competition within a free market by limiting the abuse of monopoly power. Competition allows companies to compete in order for products and services to improve; promote innovation; and provide more choices for consumers. In order to obtain greater profits, some large enterprises take advantage of market power to hinder survival of new entrants. Anti-competitive behavior can undermine the efficiency and fairness of the market, leaving consumers with little choice to obtain a reasonable quality of service.

In the European Union, competition law promotes the maintenance of competition within the European Single Market by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies to ensure that they do not create cartels and monopolies that would damage the interests of society.

Competition law is the field of law that promotes or seeks to maintain market competition by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies. Competition law is implemented through public and private enforcement. It is also known as antitrust law, anti-monopoly law, and trade practices law; the act of pushing for antitrust measures or attacking monopolistic companies is commonly known as trust busting.

The theory of the firm consists of a number of economic theories that explain and predict the nature of the firm, company, or corporation, including its existence, behaviour, structure, and relationship to the market. Firms are key drivers in economics, providing goods and services in return for monetary payments and rewards. Organisational structure, incentives, employee productivity, and information all influence the successful operation of a firm in the economy and within itself. As such major economic theories such as transaction cost theory, managerial economics and behavioural theory of the firm will allow for an in-depth analysis on various firm and management types.

In Economics and Law, exclusive dealing arises when a supplier entails the buyer by placing limitations on the rights of the buyer to choose what, who and where they deal. This is against the law in most countries which include the USA, Australia and Europe when it has a significant impact of substantially lessening the competition in an industry. When the sales outlets are owned by the supplier, exclusive dealing is because of vertical integration, where the outlets are independent exclusive dealing is illegal due to the Restrictive Trade Practices Act, however, if it is registered and approved it is allowed. While primarily those agreements imposed by sellers are concerned with the comprehensive literature on exclusive dealing, some exclusive dealing arrangements are imposed by buyers instead of sellers.

In economics, market concentration is a function of the number of firms and their respective shares of the total production in a market. Market concentration is the portion of a given market's market share that is held by a small number of businesses. To ascertain whether an industry is competitive or not, it is employed in antitrust law and economic regulation. When market concentration is high, it indicates that a few firms dominate the market and oligopoly or monopolistic competition is likely to exist. In most cases, high market concentration produces undesirable consequences such as reduced competition and higher prices.

Merger simulation is a commonly used technique when analyzing potential welfare costs and benefits of mergers between firms. Merger simulation models differ with respect to assumed form of competition that best describes the market as well as the structure of the chosen demand system

Market dominance is the control of a economic market by a firm. A dominant firm possesses the power to affect competition and influence market price. A firms' dominance is a measure of the power of a brand, product, service, or firm, relative to competitive offerings, whereby a dominant firm can behave independent of their competitors or consumers, and without concern for resource allocation. Dominant positioning is both a legal concept and an economic concept and the distinction between the two is important when determining whether a firm's market position is dominant.

Merger guidelines in the United States are a set of internal rules promulgated by the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice (DOJ) in conjunction with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). These rules have been revised over the past four decades. They govern the process by which these two regulatory bodies scrutinize and/or challenge a potential merger. Grounds for challenges include increased market concentration and threat to competition within a relevant market.

A vertical agreement is a term used in competition law to denote agreements between firms at different levels of a supply chain. For instance, a manufacturer of consumer electronics might have a vertical agreement with a retailer according to which the latter would promote their products in return for lower prices. Franchising is a form of vertical agreement, and under European Union competition law this falls within the scope of Article 101.

European Union merger law is a part of the law of the European Union. It is charged with regulating mergers between two or more entities in a corporate structure. This institution has jurisdiction over concentrations that might or might not impede competition. Although mergers must comply with policies and regulations set by the commission; certain mergers are exempt if they promote consumer welfare. Mergers that fail to comply with the common market may be blocked. It is part of competition law and is designed to ensure that firms do not acquire such a degree of market power on the free market so as to harm the interests of consumers, the economy and society as a whole. Specifically, the level of control may lead to higher prices, less innovation and production.

In competition law, a relevant market is a market in which a particular product or service is sold. It is the intersection of a relevant product market and a relevant geographic market. The European Commission defines a relevant market and its product and geographic components as follows:

- A relevant product market comprises all those products and/or services which are regarded as interchangeable or substitutable by the consumer by reason of the products' characteristics, their prices and their intended use;

- A relevant geographic market comprises the area in which the firms concerned are involved in the supply of products or services and in which the conditions of competition are sufficiently homogeneous.

Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) is aimed at preventing businesses in an industry from abusing their positions by colluding to fix prices or taking action to prevent new businesses from gaining a foothold in the industry. Its core role is the regulation of monopolies, which restrict competition in private industry and produce worse outcomes for consumers and society. It is the second key provision, after Article 101, in European Union (EU) competition law.

Mergers and acquisitions in United Kingdom law refers to a body of law that covers companies, labour, and competition, which is engaged when firms restructure their affairs in the course of business.

United States v. Philadelphia National Bank, 374 U.S. 321 (1963), also called the Philadelphia Bank case, was a 1963 decision of the United States Supreme Court that held Section 7 of the Clayton Act, as amended in 1950, applied to bank mergers. It was the first case in which the Supreme Court considered the application of antitrust laws to the commercial banking industry. In addition to holding the statute applicable to bank mergers, the Court established a presumption that mergers that covered at least 30 percent of the relevant market were presumptively unlawful.

Mergers in United Kingdom law is a theory-based regulation that helps forecast and avoid abuse, while indirectly maintaining a competitive framework within the market. A true merger is one in which two separate entities merge into an entirely new entity. In Law the term ‘merger’ has a much broader application, for example where A acquires all, or a majority of, the shares in B, and is able to control the affairs of B as such.