Hate speech is a legal term with varied meaning. It has no single, consistent definition. It is defined by the Cambridge Dictionary as "public speech that expresses hate or encourages violence towards a person or group based on something such as race, religion, sex, or sexual orientation". The Encyclopedia of the American Constitution states that hate speech is "usually thought to include communications of animosity or disparagement of an individual or a group on account of a group characteristic such as race, color, national origin, sex, disability, religion, or sexual orientation". There is no single definition of what constitutes "hate" or "disparagement". Legal definitions of hate speech vary from country to country.

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic media, especially published materials, should be considered a right to be exercised freely. Such freedom implies the absence of interference from an overreaching state; its preservation may be sought through the constitution or other legal protection and security. It is in opposition to paid press, where communities, police organizations, and governments are paid for their copyrights.

Censorship in the United Kingdom was at different times more or less widely applied to various forms of expression such as the press, cinema, entertainment venues, literature, theatre and criticism of the monarchy. While there is no general right to free speech in the UK, British citizens have a negative right to freedom of expression under the common law, and since 1998, freedom of expression is guaranteed according to Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, as applied in British law through the Human Rights Act.

The Federal Department for the Protection of Children and Young People in the Media (German: Bundeszentrale für Kinder- und Jugendmedienschutz or BzKJ), until 2021 "Federal Department for Media Harmful to Young Persons", is an upper-level German federal agency subordinate to the Federal Ministry of Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth. It is responsible for examining media works suspected to be harmful to young people. These works are added to an official list – a process known as Indizierung (indexing) in German - as part of child protection efforts. The decision to index a work has a variety of legal implications; chiefly, restrictions on sale and advertisement.

Germany has taken many forms throughout the history of censorship in the country. Various regimes have restricted the press, cinema, literature, and other entertainment venues. In contemporary Germany, the Grundgesetz generally guarantees freedom of press, speech, and opinion.

Internet censorship is the legal control or suppression of what can be accessed, published, or viewed on the Internet. Censorship is most often applied to specific internet domains but exceptionally may extend to all Internet resources located outside the jurisdiction of the censoring state. Internet censorship may also put restrictions on what information can be made internet accessible. Organizations providing internet access – such as schools and libraries – may choose to preclude access to material that they consider undesirable, offensive, age-inappropriate or even illegal, and regard this as ethical behavior rather than censorship. Individuals and organizations may engage in self-censorship of material they publish, for moral, religious, or business reasons, to conform to societal norms, political views, due to intimidation, or out of fear of legal or other consequences.

Most Internet censorship in Thailand prior to the September 2006 military coup d'état was focused on blocking pornographic websites. The following years have seen a constant stream of sometimes violent protests, regional unrest, emergency decrees, a new cybercrimes law, and an updated Internal Security Act. Year by year Internet censorship has grown, with its focus shifting to lèse majesté, national security, and political issues. By 2010, estimates put the number of websites blocked at over 110,000. In December 2011, a dedicated government operation, the Cyber Security Operation Center, was opened. Between its opening and March 2014, the Center told ISPs to block 22,599 URLs.

Freedom of speech is the concept of the inherent human right to voice one's opinion publicly without fear of censorship or punishment. "Speech" is not limited to public speaking and is generally taken to include other forms of expression. The right is preserved in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and is granted formal recognition by the laws of most nations. Nonetheless, the degree to which the right is upheld in practice varies greatly from one nation to another. In many nations, particularly those with authoritarian forms of government, overt government censorship is enforced. Censorship has also been claimed to occur in other forms and there are different approaches to issues such as hate speech, obscenity, and defamation laws.

Although Internet censorship in Germany is traditionally been rated as low, it is practised directly and indirectly through various laws and court decisions. German law provides for freedom of speech and press with several exceptions, including what The Guardian has called "some of the world's toughest laws around hate speech". An example of content censored by law is the removal of web sites from Google search results that deny the holocaust, which is a felony under German law. According to the Google Transparency Report, the German government is frequently one of the most active in requesting user data after the United States. However, in Freedom House's Freedom On the Net 2022 Report, Germany was rated the eighth most free of the 70 countries rated.

Facebook is a social networking service that has been gradually replacing traditional media channels since 2010. Facebook has limited moderation of the content posted to its site. Because the site indiscriminately displays material publicly posted by users, Facebook can, in effect, threaten oppressive governments. Facebook can simultaneously propagate fake news, hate speech, and misinformation, thereby undermining the credibility of online platforms and social media.

Internet censorship in South Korea is prevalent, and contains some unique elements such as the blocking of pro-North Korea websites, and to a lesser extent, Japanese websites, which led to it being categorized as "pervasive" in the conflict/security area by OpenNet Initiative. South Korea is also one of the few developed countries where pornography is largely illegal, with the exception of social media websites which are a common source of legal pornography in the country. Any and all material deemed "harmful" or subversive by the state is censored. The country also has a "cyber defamation law", which allow the police to crack down on comments deemed "hateful" without any reports from victims, with citizens being sentenced for such offenses.

There is medium internet censorship in France, including limited filtering of child pornography, laws against websites that promote terrorism or racial hatred, and attempts to protect copyright. The "Freedom on the Net" report by Freedom House has consistently listed France as a country with Internet freedom. Its global ranking was 6 in 2013 and 12 in 2017. A sharp decline in its score, second only to Libya was noted in 2015 and attributed to "problematic policies adopted in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attack, such as restrictions on content that could be seen as 'apology for terrorism,' prosecutions of users, and significantly increased surveillance."

Freedom of expression in Canada is protected as a "fundamental freedom" by section 2 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms; however, in practice the Charter permits the government to enforce "reasonable" limits censoring speech. Hate speech, obscenity, and defamation are common categories of restricted speech in Canada. During the 1970 October Crisis, the War Measures Act was used to limit speech from the militant political opposition.

Mass media regulations are a form of media policy with rules enforced by the jurisdiction of law. Guidelines for media use differ across the world. This regulation, via law, rules or procedures, can have various goals, for example intervention to protect a stated "public interest", or encouraging competition and an effective media market, or establishing common technical standards.

Heiko Josef Maas is a German lawyer and former politician of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) who served as the Federal Minister of Foreign Affairs (2018–2021) and as the Federal Minister of Justice and Consumer Protection (2013–2018) in the cabinet of Chancellor Angela Merkel. Since 2022, he has been practicing as a lawyer.

Media freedom in the European Union is a fundamental right that applies to all member states of the European Union and its citizens, as defined in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights as well as the European Convention on Human Rights. Within the EU enlargement process, guaranteeing media freedom is named a "key indicator of a country's readiness to become part of the EU".

Facebook has been involved in multiple controversies involving censorship of content, removing or omitting information from its services in order to comply with company policies, legal demands, and government censorship laws.

Online hate speech is a type of speech that takes place online with the purpose of attacking a person or a group based on their race, religion, ethnic origin, sexual orientation, disability, and/or gender. Online hate speech is not easily defined, but can be recognized by the degrading or dehumanizing function it serves.

Freedom of the press in Bhutan is an ongoing social and political controversy in the country of Bhutan, particularly prior to the introduction of multiparty democracy in the country. Bhutanese journalists are reported to have limited access to the right to the freedom of the press which may be in contravention of Bhutan's 2008 Constitution.

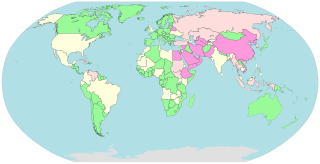

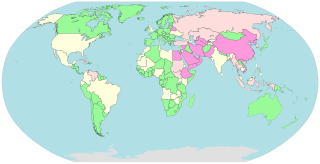

This list of Internet censorship and surveillance in Europe provides information on the types and levels of Internet censorship and surveillance that is occurring in countries in Europe.