The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil War against the Kuomintang. In 1949, Mao proclaimed the establishment of the People's Republic of China. Since then, the CCP has governed China and has had sole control over the People's Liberation Army (PLA). Successive leaders of the CCP have added their own theories to the party's constitution, which outlines the party's ideology, collectively referred to as socialism with Chinese characteristics. As of 2023, the CCP has more than 98 million members, making it the second largest political party by membership in the world after India's Bharatiya Janata Party.

Deng Xiaoping was a Chinese revolutionary and high ranking politician who served as the paramount leader of the People's Republic of China (PRC) from December 1978 to November 1989. After Chinese Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong's death in 1976, Deng rose to power and led China through its process of Reform and Opening Up and the development of the country's socialist market economy. Deng developed a reputation as the "Architect of Modern China" and his ideological contributions to socialism with Chinese characteristics are described as Deng Xiaoping Theory.

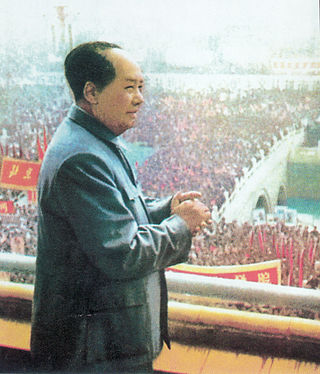

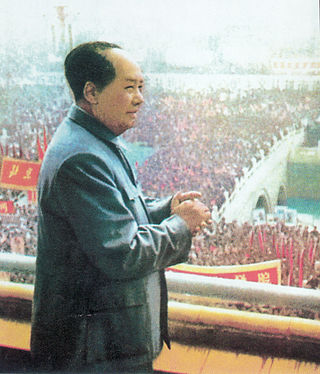

Mao Zedong was a Chinese politician, Marxist theorist, military strategist, poet, and revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC). He led the country from its establishment in 1949 until his death in 1976, while also serving as the chairman of the Chinese Communist Party during that time. His theories, military strategies and policies are known as Maoism.

Maoism, also known as Mao Zedong Thought, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed while trying to realize a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of China and later the People's Republic of China. A difference between Maoism and traditional Marxism–Leninism is that a united front of progressive forces in class society would lead the revolutionary vanguard in pre-industrial societies rather than communist revolutionaries alone. This theory, in which revolutionary praxis is primary and ideological orthodoxy is secondary, represents urban Marxism–Leninism adapted to pre-industrial China. Later theoreticians expanded on the idea that Mao had adapted Marxism–Leninism to Chinese conditions, arguing that he had in fact updated it fundamentally and that Maoism could be applied universally throughout the world. This ideology is often referred to as Marxism–Leninism–Maoism to distinguish it from the original ideas of Mao.

Zhou Enlai was a Chinese statesman, diplomat, and revolutionary who served as the first Premier of the People's Republic of China from September 1954 until his death in January 1976. Zhou served under Chairman Mao Zedong and aided the Communist Party in rising to power, later helping consolidate its control, form its foreign policy, and develop the Chinese economy.

The time period in China from the founding of the People's Republic in 1949 until Mao's death in 1976 is commonly known as Maoist China and Red China. The history of the People's Republic of China is often divided distinctly by historians into the Mao era and the post-Mao era. The country's Mao era lasted from the founding of the People's republic on 1 October 1949 to Deng Xiaoping's consolidation of power and policy reversal at the Third Plenum of the 11th Party Congress on 22 December 1978. The Mao era focuses on Mao Zedong's social movements from the early 1950s on, including land reform, the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. The Great Chinese Famine, one of the worst famines in human history, occurred during this era.

The Hundred Flowers Campaign, also termed the Hundred Flowers Movement, was a period from 1956 to 1957 in the People's Republic of China during which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) encouraged citizens to openly express their opinions of the Communist Party.

The Anti-Rightist Campaign in the People's Republic of China, which lasted from 1957 to roughly 1959, was a political campaign to purge alleged "Rightists" within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the country as a whole. The campaign was launched by Chairman Mao Zedong, but Deng Xiaoping and Peng Zhen also played an important role. The Anti-Rightist Campaign significantly damaged democracy in China and turned the country into a de facto one-party state.

The Sino-Soviet split was the gradual deterioration of relations between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) during the Cold War. This was primarily caused by doctrinal divergences that arose from their different interpretations and practical applications of Marxism–Leninism, as influenced by their respective geopolitics during the Cold War of 1947–1991. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Sino-Soviet debates about the interpretation of orthodox Marxism became specific disputes about the Soviet Union's policies of national de-Stalinization and international peaceful coexistence with the Western Bloc, which Chinese founding father Mao Zedong decried as revisionism. Against that ideological background, China took a belligerent stance towards the Western world, and publicly rejected the Soviet Union's policy of peaceful coexistence between the Western Bloc and Eastern Bloc. In addition, Beijing resented the Soviet Union's growing ties with India due to factors such as the Sino-Indian border dispute, and Moscow feared that Mao was too nonchalant about the horrors of nuclear warfare.

Ping-pong diplomacy refers to the exchange of table tennis (ping-pong) players between the United States and the People's Republic of China in the early 1970s. Considered a turning point in relations between the United States and the People's Republic of China, it began during the 1971 World Table Tennis Championships in Nagoya, Japan, as a result of an encounter between players Glenn Cowan and Zhuang Zedong. The exchange and its promotion helped people in each country to recognize the humanity in the people of the other country, and it paved the way for President Richard Nixon's visit to Beijing in 1972.

The time period in China from the death of Mao Zedong in 1976 until the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre is often known as Dengist China. In September 1976, after Chairman Mao Zedong's death, the People's Republic of China was left with no central authority figure, either symbolically or administratively. The Gang of Four was purged, but new Chairman Hua Guofeng insisted on continuing Maoist policies. After a bloodless power struggle, Deng Xiaoping came to the helm to reform the Chinese economy and government institutions in their entirety. Deng, however, was conservative with regard to wide-ranging political reform, and along with the combination of unforeseen problems that resulted from the economic reform policies, the country underwent another political crisis, culminating in the crackdown of massive pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square.

The 1972 visit by United States president Richard Nixon to the People's Republic of China was an important strategic and diplomatic overture that marked the culmination of the Nixon administration's establishment of relations between the United States of America and the People's Republic of China after years of American diplomatic policy that favored the Republic of China in Taiwan. The seven-day official visit to three Chinese cities was the first time a U.S. president had visited the PRC; Nixon's arrival in Beijing ended 25 years of no communication or diplomatic ties between the two countries and was the key step in normalizing relations between the U.S. and the PRC. Nixon visited the PRC to gain more leverage over relations with the Soviet Union, following the Sino-Soviet split. The normalization of ties culminated in 1979, when the U.S. established full diplomatic relations with the PRC.

The history of the People's Republic of China details the history of mainland China since 1 October 1949, when CCP chairman Mao Zedong proclaimed the People's Republic of China (PRC) from atop Tiananmen, after a near complete victory (1949) by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in the Chinese Civil War. The PRC is the most recent political entity to govern mainland China, preceded by the Republic of China and thousands of years of monarchical dynasties. The paramount leaders have been Mao Zedong (1949–1976); Hua Guofeng (1976–1978); Deng Xiaoping (1978–1989); Jiang Zemin (1989–2002); Hu Jintao (2002–2012); and Xi Jinping.

Deng Xiaoping Theory, also known as Dengism, is the series of political and economic ideologies first developed by Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping. The theory does not reject Marxism–Leninism or Maoism, but instead claims to be an adaptation of them to the existing socioeconomic conditions of China.

Ji Chaozhu was a Chinese English language diplomatic interpreter and diplomat who held diverse positions in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Most notably, he was English interpreter for Chairman Mao Zedong, Premier Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping, Ambassador to the Court of St. James's, and then served as an Under-secretary General of the United Nations, a post from which he retired in 1996. He was one of the principle interpreters in the talks leading up to and during President Richard M. Nixon's historic 1972 visit to China.

On China is a 2011 non-fiction book by Henry Kissinger, former National Security Adviser and United States Secretary of State. The book is part an effort to make sense of China's strategy in diplomacy and foreign policy over 3000 years and part an attempt to provide an authentic insight on Chinese Communist Party leaders. Kissinger, considered one of the most famous diplomats of the 20th century, played an integral role in developing the relationship between the United States and the People's Republic of China during the Nixon administration, which culminated in Nixon's 1972 visit to China.

Li Jingquan was a Chinese politician and the first Party Committee Secretary (governor) of Sichuan following the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949. He supported many of Mao Zedong's policies including the Great Leap Forward.

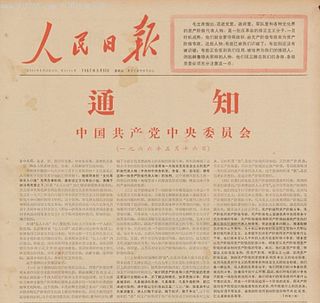

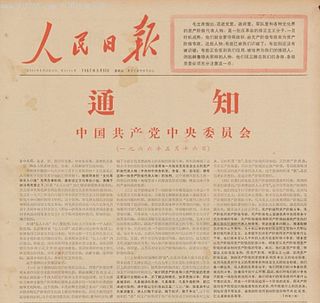

The 16 May Notification or Circular of 16 May, originally titled simply Notification, was the initial political declaration of the Cultural Revolution. Initially a secret inner-party document, it was issued at a May 1966 expanded session of the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party. The notification ended a political dispute within the CCP stemming from the Beijing Opera play Hai Rui Dismissed from Office by dissolving the top level of the party's cultural apparatus and encouraging mass political movement to oppose rightists within the party. The result was a political victory for Mao Zedong. The Notification is often viewed as the beginning of the Cultural Revolution and would be declassified and published in People's Daily on 17 May 1967.

Mao Zedong's cult of personality was a prominent part of Chairman Mao Zedong's rule over the People's Republic of China from the state's founding in 1949 until his death in 1976. Mass media, propaganda and a series of other techniques were used by the state to elevate Mao Zedong's status to that of an infallible heroic leader, who could stand up against the West, and guide China to become a beacon of communism.

Mao Zedong, also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who became the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC), which he ruled as the Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party from its establishment in 1949 until his death on 9 September 1976, at the age of 82.