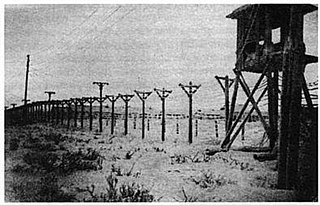

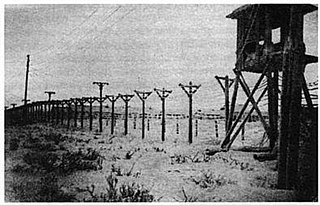

The Gulag was a system of forced labor camps in the Soviet Union. The word Gulag originally referred only to the division of the Soviet secret police that was in charge of running the forced labor camps from the 1930s to the early 1950s during Joseph Stalin's rule, but in English literature the term is popularly used for the system of forced labor throughout the Soviet era. The abbreviation GULAG (ГУЛАГ) stands for "Гла́вное Управле́ние исправи́тельно-трудовы́х ЛАГере́й", but the full official name of the agency changed several times.

Butyrskaya prison, usually known simply as Butyrka, is a prison in the Tverskoy District of central Moscow, Russia. In Imperial Russia it served as the central transit prison. During the Soviet Union era (1917–1991) it held many political prisoners. As of 2022 Butyrka remains the largest of Moscow's remand prisons. Overcrowding is an ongoing problem.

The Solovki special camp, was set up in 1923 on the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea as a remote and inaccessible place of detention, primarily intended for socialist opponents of Soviet Russia's new Bolshevik regime.

Kolyma or Kolyma Krai is a historical region in the Russian Far East that includes the basin of Kolyma River and the northern shores of the Sea of Okhotsk, as well as the Kolyma Mountains. It is bounded to the north by the East Siberian Sea and the Arctic Ocean, and by the Sea of Okhotsk to the south. Kolyma Krai was never formally defined and over time it was split among various administrative units. As of 2023, it consists roughly of the Magadan Oblast, north-eastern areas of Yakutia, and the Bilibinsky District of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug.

Penal labour is a term for various kinds of forced labour that prisoners are required to perform, typically manual labour. The work may be light or hard, depending on the context. Forms of sentence involving penal labour have included involuntary servitude, penal servitude, and imprisonment with hard labour. The term may refer to several related scenarios: labour as a form of punishment, the prison system used as a means to secure labour, and labour as providing occupation for convicts. These scenarios can be applied to those imprisoned for political, religious, war, or other reasons as well as to criminal convicts.

Yevhen Mykhailovych Konovalets, was a Ukrainian military commander and political leader of the Ukrainian nationalist movement.

Dmitry Nikolaevich Medvedev was one of the leaders of the Soviet partisan movement in western Russia and Ukraine.

The Kengir uprising was a prisoner rebellion that occurred in Kengir (Steplag), a Soviet MVD special camp for political prisoners, during May and June 1954. Its duration and intensity distinguished it from other Gulag rebellions during the same period.

The Vorkuta Uprising was a major uprising of forced labor camp inmates at the Rechlag Gulag special labor camp in Vorkuta, Russian SFSR, USSR from 19 July to 1 August 1953, shortly after the arrest of Lavrentiy Beria. The uprising was violently stopped by the camp administration after two weeks of bloodless standoff.

John H. Noble was an American survivor of the Soviet Gulag system, who wrote several books which described his experiences in it after he was permitted to leave the Soviet Union and return to the United States.

Norillag, Norilsk Corrective Labor Camp was a gulag labor camp set by Norilsk, Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia and headquartered there. It existed from June 25, 1935 to August 22, 1956.

Danylo Lavrentiyovych Shumuk was a Ukrainian political activist who served a total of 42 years imprisoned by three different states, Second Polish Republic, Nazi Germany and Soviet Union.

Gulag: A History, also published as Gulag: A History of the Soviet Camps, is a non-fiction book covering the history of the Soviet Gulag system. It was written by American author Anne Applebaum and published in 2003 by Doubleday. Gulag won the 2004 Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction and the 2004 Duff Cooper Prize. It was also nominated for the National Book Critics Circle prize and for the National Book Award.

A corrective colony is the most common type of prison in Russia and some other post-Soviet states. Such colonies combine penal detention with compulsory work. The system of labor colonies and camps originated in 1929, and after 1953, the corrective penal colonies in the Soviet Union developed as a post-Stalin replacement of the Gulag labor camp system.

Pavel Ivanovich Prudnikau was a Belarusian writer. He was a cousin of another Belarusian writer, Ales Prudnikau.

The Vorkuta Corrective Labor Camp, commonly known as Vorkutlag (Воркутлаг), was a major Gulag labor camp in the Soviet Union located in Vorkuta, Komi Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic from 1932 to 1962.

The Dubravny Camp, Special Camp No.3, commonly known as the Dubravlag, was a Gulag labor camp of the Soviet Union located in Yavas, Mordovia from 1948 to 2005.

MVD special camps of the Gulag was a system of special labor camps established addressing the February 21, 1948 decree 416—159сс of the USSR Council of Ministers of February 28 decree 00219 of the Soviet Ministry of Internal Affairs exclusively for a "special contingent" of political prisoners, convicted according to the more severe sub-articles of Article 58 : treason, espionage, terrorism, etc., for various real political opponents, such as Trotskyists, "nationalists", white émigrés, as well as for fabricated ones.

Gorlag or Gorny Camp Directorate, Special Camp No. 2 ) was an MVD special camp for political prisoners within the Gulag system of the Soviet Union. It was established on February 28, 1948 on the part of the premises of Norillag, Norilsk, Krasnoyarsk Krai, RSFSR. In 1954, after Stalin's death it was merged back into Norillag, which was closed in 1957 together with most of the Gulag system.

Aleksandra Matveena Zelenskaya was a political prisoner in the gulag system of the Soviet Union who was the leader of the Norilsk uprising of the 6th Women's Camp at Gorlag.