Over-the-counter (OTC) drugs are medicines sold directly to a consumer without a requirement for a prescription from a healthcare professional, as opposed to prescription drugs, which may be supplied only to consumers possessing a valid prescription. In many countries, OTC drugs are selected by a regulatory agency to ensure that they contain ingredients that are safe and effective when used without a physician's care. OTC drugs are usually regulated according to their active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) rather than final products. By regulating APIs instead of specific drug formulations, governments allow manufacturers the freedom to formulate ingredients, or combinations of ingredients, into proprietary mixtures.

A prescription, often abbreviated ℞ or Rx, is a formal communication from a physician or other registered healthcare professional to a pharmacist, authorizing them to dispense a specific prescription drug for a specific patient. Historically, it was a physician's instruction to an apothecary listing the materials to be compounded into a treatment—the symbol ℞ comes from the first word of a medieval prescription, Latin recipere, that gave the list of the materials to be compounded.

A prescription drug is a pharmaceutical drug that is permitted to be dispensed only to those with a medical prescription. In contrast, over-the-counter drugs can be obtained without a prescription. The reason for this difference in substance control is the potential scope of misuse, from drug abuse to practicing medicine without a license and without sufficient education. Different jurisdictions have different definitions of what constitutes a prescription drug.

Controversies regarding the use of human growth hormone (HGH) as treatment method have centered on the claims, products, and businesses related to the use of growth hormone as an anti-aging therapy. Most of these controversies fall into two categories:

- Claims of exaggerated, misleading, or unfounded assertions that growth hormone treatment safely and effectively slows or reverses the effects of aging.

- The sale of products that fraudulently or misleadingly purport to be growth hormone or to increase the user's own secretion of natural human growth hormone to a beneficial degree.

Pharmaceutical marketing is a branch of marketing science and practice focused on the communication, differential positioning and commercialization of pharmaceutical products, like specialist drugs, biotech drugs and over-the-counter drugs. By extension, this definition is sometimes also used for marketing practices applied to nutraceuticals and medical devices.

Dextropropoxyphene is an analgesic in the opioid category, patented in 1955 and manufactured by Eli Lilly and Company. It is an optical isomer of levopropoxyphene. It is intended to treat mild pain and also has antitussive and local anaesthetic effects. The drug has been taken off the market in Europe and the US due to concerns of fatal overdoses and heart arrhythmias. It is still available in Australia, albeit with restrictions after an application by its manufacturer to review its proposed banning. Its onset of analgesia is said to be 20–30 minutes and peak effects are seen about 1.5–2.0 hours after oral administration.

Cilostazol, sold under the brand name Pletal among others, is a medication used to help the symptoms of intermittent claudication in peripheral vascular disease. If no improvement is seen after 3 months, stopping the medication is reasonable. It may also be used to prevent stroke. It is taken by mouth.

An approved drug is a medicinal preparation that has been validated for a therapeutic use by a ruling authority of a government. This process is usually specific by country, unless specified otherwise.

A package insert is a document included in the package of a medication that provides information about that drug and its use. For prescription medications, the insert is technical, providing information for medical professionals about how to prescribe the drug. Package inserts for prescription drugs often include a separate document called a "patient package insert" with information written in plain language intended for the end-user—the person who will take the drug or give the drug to another person, such as a minor. Inserts for over-the-counter medications are also written plainly.

Direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) refers to the marketing and advertising of pharmaceutical products directly to consumers as patients, as opposed to specifically targeting health professionals. The term is synonymous primarily with the advertising of prescription medicines via mass media platforms—most commonly on television and in magazines, but also via online platforms.

In medicine, an indication is a valid reason to use a certain test, medication, procedure, or surgery. There can be multiple indications to use a procedure or medication. An indication can commonly be confused with the term diagnosis. A diagnosis is the assessment that a particular [medical] condition is present while an indication is a reason for use. The opposite of an indication is a contraindication, a reason to withhold a certain medical treatment because the risks of treatment clearly outweigh the benefits.

Omega-3-acid ethyl esters are a mixture of ethyl eicosapentaenoic acid and ethyl docosahexaenoic acid, which are ethyl esters of the omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) found in fish oil. Together with dietary changes, they are used to treat high blood triglycerides which may reduce the risk of pancreatitis. They are generally less preferred than statins, and use is not recommended by NHS Scotland as the evidence does not support a decreased risk of heart disease. Omega-3-acid ethyl esters are taken by mouth.

Ethyl eicosapentaenoic acid, sold under the brand name Vascepa among others, is a medication used to treat dyslipidemia and hypertriglyceridemia. It is used in combination with changes in diet in adults with hypertriglyceridemia ≥ 150 mg/dL. Further, it is often required to be used with a statin.

Pharmaceutical fraud involves activities that result in false claims to insurers or programs such as Medicare in the United States or equivalent state programs for financial gain to a pharmaceutical company. There are several different schemes used to defraud the health care system which are particular to the pharmaceutical industry. These include: Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) Violations, Off Label Marketing, Best Price Fraud, CME Fraud, Medicaid Price Reporting, and Manufactured Compound Drugs. Examples of fraud cases include the GlaxoSmithKline $3 billion settlement, Pfizer $2.3 billion settlement, and Merck $650 million settlement. Damages from fraud can be recovered by use of the False Claims Act, most commonly under the qui tam provisions which rewards an individual for being a "whistleblower", or relator (law).

Franklin v. Parke-Davis is a lawsuit filed in 1996 against Parke-Davis, a division of Warner-Lambert Company, and eventually against Pfizer under the qui tam provisions of the False Claims Act. The suit was commenced by David Franklin, a microbiologist hired in the spring of 1996 in a sales capacity at Parke-Davis, a pharmaceutical subsidiary of Warner-Lambert. In denying the defendants' motion for summary judgment, the court for the first time recognized off-label promotion of drugs could cause Medicaid to pay for prescriptions that were not reimbursable, triggering False Claims Act liability. The case was also significant in exposing the degree to which publication bias impacts the randomized controlled studies conducted by pharmaceutical companies to test the efficacy of their products. Ultimately, the parties reached a settlement agreement of $430 million to resolve all civil claims and criminal charges stemming from the qui tam complaint. At the time of the settlement in May 2004, it represented one of the largest False Claims Act recoveries against a pharmaceutical company in U.S. history, and was the first off-label promotion settlement under the False Claims Act.

Marketing of off-label use is advertising the use of drugs for purposes not approved by the regional government. The practice is often illegal and has led to most of the largest pharmaceutical settlements after Franklin v. Parke-Davis, in which a court ruled off-label marketing a violation of the False Claims Act.

Digital medicine refers to the application of advanced digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, and big data analytics, to improve patient outcomes and healthcare delivery. It involves the integration of technology and medicine to facilitate the creation, storage, analysis, and dissemination of health information, with the aim of enhancing clinical decision-making, improving patient care, and reducing costs.

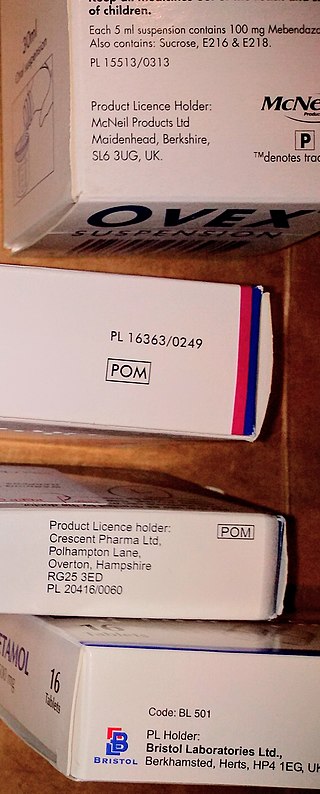

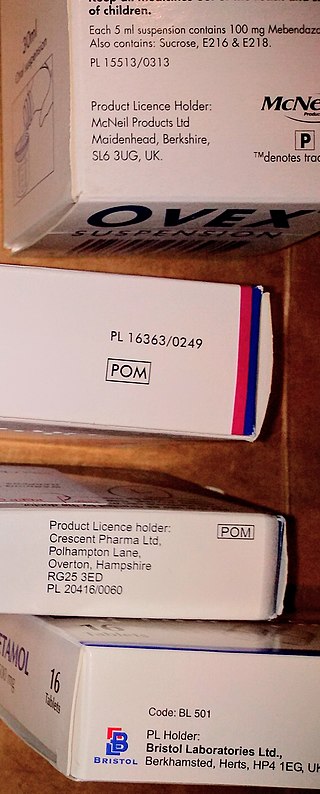

Drug labelling is also referred to as prescription labelling, is a written, printed or graphic matter upon any drugs or any of its container, or accompanying such a drug. Drug labels seek to identify drug contents and to state specific instructions or warnings for administration, storage and disposal. Since 1800s, legislation has been advocated to stipulate the formats of drug labelling due to the demand for an equitable trading platform, the need of identification of toxins and the awareness of public health. Variations in healthcare system, drug incidents and commercial utilization may attribute to different regional or national drug label requirements. Despite the advancement in drug labelling, medication errors are partly associated with undesirable drug label formatting.