A dictionary is a listing of lexemes from the lexicon of one or more specific languages, often arranged alphabetically, which may include information on definitions, usage, etymologies, pronunciations, translation, etc. It is a lexicographical reference that shows inter-relationships among the data.

The identity of the longest word in English depends on the definition of a word and of length.

English orthography is the writing system used to represent spoken English, allowing readers to connect the graphemes to sound and to meaning. It includes English's norms of spelling, hyphenation, capitalisation, word breaks, emphasis, and punctuation.

A rhyme is a repetition of similar sounds in the final stressed syllables and any following syllables of two or more words. Most often, this kind of perfect rhyming is consciously used for a musical or aesthetic effect in the final position of lines within poems or songs. More broadly, a rhyme may also variously refer to other types of similar sounds near the ends of two or more words. Furthermore, the word rhyme has come to be sometimes used as a shorthand term for any brief poem, such as a nursery rhyme or Balliol rhyme.

U, or u, is the twenty-first letter and the fifth vowel letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is u, plural ues.

V, or v, is the twenty-second letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is vee, plural vees.

Spelling is a set of conventions for written language regarding how graphemes should correspond to the sounds of spoken language. Spelling is one of the elements of orthography, and highly standardized spelling is a prescriptive element.

Merriam-Webster, Incorporated is an American company that publishes reference books and is mostly known for its dictionaries. It is the oldest dictionary publisher in the United States.

Folk etymology – also known as (generative) popular etymology, analogical reformation, (morphological)reanalysis and etymological reinterpretation – is a change in a word or phrase resulting from the replacement of an unfamiliar form by a more familiar one through popular usage. The form or the meaning of an archaic, foreign, or otherwise unfamiliar word is reinterpreted as resembling more familiar words or morphemes.

Stress is a prominent feature of the English language, both at the level of the word (lexical stress) and at the level of the phrase or sentence (prosodic stress). Absence of stress on a syllable, or on a word in some cases, is frequently associated in English with vowel reduction – many such syllables are pronounced with a centralized vowel (schwa) or with certain other vowels that are described as being "reduced". Various phonological analyses exist for these phenomena.

There are a variety of pronunciations in modern English and in historical forms of the language for words spelled with the letter ⟨a⟩. Most of these go back to the low vowel of earlier Middle English, which later developed both long and short forms. The sound of the long vowel was altered in the Great Vowel Shift, but later a new long A developed which was not subject to the shift. These processes have produced the main four pronunciations of ⟨a⟩ in present-day English: those found in the words trap, face, father and square. Separate developments have produced additional pronunciations in words like wash, talk and comma.

In English, many vowel shifts affect only vowels followed by in rhotic dialects, or vowels that were historically followed by that has been elided in non-rhotic dialects. Most of them involve the merging of vowel distinctions and so fewer vowel phonemes occur before than in other positions of a word.

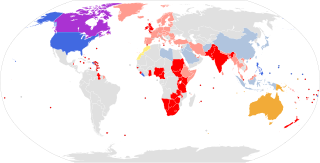

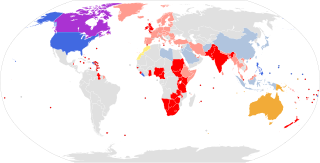

Despite the various English dialects spoken from country to country and within different regions of the same country, there are only slight regional variations in English orthography, the two most notable variations being British and American spelling. Many of the differences between American and British/Commonwealth English date back to a time before spelling standards were developed. For instance, some spellings seen as "American" today were once commonly used in Britain, and some spellings seen as "British" were once commonly used in the United States.

Differences in pronunciation between American English (AmE) and British English (BrE) can be divided into

A pronunciation respelling for English is a notation used to convey the pronunciation of words in the English language, which do not have a phonemic orthography.

In the Latin-based orthographies of many European languages, including English, a distinction between hard and soft ⟨c⟩ occurs in which ⟨c⟩ represents two distinct phonemes. The sound of a hard ⟨c⟩ often precedes the non-front vowels ⟨a⟩, ⟨o⟩ and ⟨u⟩, and is that of the voiceless velar stop,. The sound of a soft ⟨c⟩, typically before ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩ and ⟨y⟩, may be a fricative or affricate, depending on the language. In English, the sound of soft ⟨c⟩ is.

A hyperforeignism is a type of qualitative hypercorrection that involves speakers misidentifying the distribution of a pattern found in loanwords and extending it to other environments, including words and phrases not borrowed from the language that the pattern derives from. The result of this process does not reflect the rules of either language. For example, habanero is sometimes pronounced as though it were spelled with an ⟨ñ⟩ (habañero), which is not the Spanish form from which the English word was borrowed.

The articles in English are the definite article the and the indefinite articles a and an. They are the two most common determiners. The definite article is the default determiner when the speaker believes that the listener knows the identity of a common noun's referent. The indefinite article is the default determiner for other singular, countable, common nouns, while no determiner is the default for other common nouns. Other determiners are used to add semantic information such as amount, proximity, or possession.