A web browser is an application for accessing websites. When a user requests a web page from a particular website, the browser retrieves its files from a web server and then displays the page on the user's screen. Browsers are used on a range of devices, including desktops, laptops, tablets, and smartphones. In 2020, an estimated 4.9 billion people have used a browser. The most used browser is Google Chrome, with a 65% global market share on all devices, followed by Safari with 18%.

Information privacy is the relationship between the collection and dissemination of data, technology, the public expectation of privacy, contextual information norms, and the legal and political issues surrounding them. It is also known as data privacy or data protection.

Internet privacy involves the right or mandate of personal privacy concerning the storing, re-purposing, provision to third parties, and displaying of information pertaining to oneself via Internet. Internet privacy is a subset of data privacy. Privacy concerns have been articulated from the beginnings of large-scale computer sharing and especially relate to mass surveillance enabled by the emergence of computer technologies.

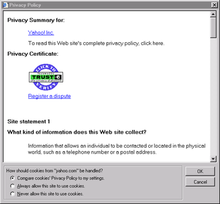

A privacy policy is a statement or legal document that discloses some or all of the ways a party gathers, uses, discloses, and manages a customer or client's data. Personal information can be anything that can be used to identify an individual, not limited to the person's name, address, date of birth, marital status, contact information, ID issue, and expiry date, financial records, credit information, medical history, where one travels, and intentions to acquire goods and services. In the case of a business, it is often a statement that declares a party's policy on how it collects, stores, and releases personal information it collects. It informs the client what specific information is collected, and whether it is kept confidential, shared with partners, or sold to other firms or enterprises. Privacy policies typically represent a broader, more generalized treatment, as opposed to data use statements, which tend to be more detailed and specific.

HTTP cookies are small blocks of data created by a web server while a user is browsing a website and placed on the user's computer or other device by the user's web browser. Cookies are placed on the device used to access a website, and more than one cookie may be placed on a user's device during a session.

A local shared object (LSO), commonly called a Flash cookie, is a piece of data that websites that use Adobe Flash may store on a user's computer. Local shared objects have been used by all versions of Flash Player since version 6.

A click path or clickstream is the sequence of hyperlinks one or more website visitors follows on a given site, presented in the order viewed. A visitor's click path may start within the website or at a separate third party website, often a search engine results page, and it continues as a sequence of successive webpages visited by the user. Click paths take call data and can match it to ad sources, keywords, and/or referring domains, in order to capture data.

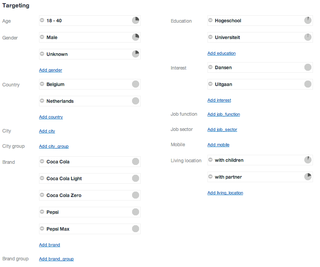

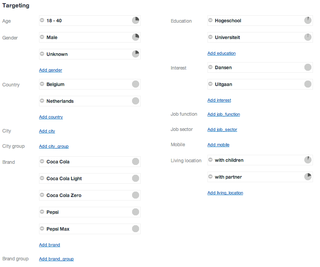

Targeted advertising is a form of advertising, including online advertising, that is directed towards an audience with certain traits, based on the product or person the advertiser is promoting. These traits can either be demographic with a focus on race, economic status, sex, age, generation, level of education, income level, and employment, or psychographic focused on the consumer values, personality, attitude, opinion, lifestyle and interest. This focus can also entail behavioral variables, such as browser history, purchase history, and other recent online activities. The process of algorithm targeting eliminates waste.

In computing, Google Dashboard lets users of the Internet view and manage personal data collected about them by Google. With an account, Google Dashboard allows users to have a summary view of their Google+, Google location history, Google web history, Google Play apps, YouTube and more. Once logged in, it summarizes data for each product the user uses and provides direct links to the products. The program allows setting preferences for personal account products.

Web tracking is the practice by which operators of websites and third parties collect, store and share information about visitors’ activities on the World Wide Web. Analysis of a user's behaviour may be used to provide content that enables the operator to infer their preferences and may be of interest to various parties, such as advertisers. Web tracking can be part of visitor management.

Evercookie is a JavaScript application programming interface (API) that identifies and reproduces intentionally deleted cookies on the clients' browser storage. It was created by Samy Kamkar in 2010 to demonstrate the possible infiltration from the websites that use respawning. Websites that have adopted this mechanism can identify users even if they attempt to delete the previously stored cookies.

Web browsing history refers to the list of web pages a user has visited, as well as associated metadata such as page title and time of visit. It is usually stored locally by web browsers in order to provide the user with a history list to go back to previously visited pages. It can reflect the user's interests, needs, and browsing habits.

A zombie cookie is a piece of data that could be stored in multiple locations -- since failure of removing all copies of the zombie cookie will make the removal reversible, zombie cookies can be difficult to remove. Since they do not entirely rely on normal cookie protocols, the visitor's web browser may continue to recreate deleted cookies even though the user has opted not to receive cookies.

Do Not Track (DNT) is a formerly official HTTP header field, designed to allow internet users to opt-out of tracking by websites—which includes the collection of data regarding a user's activity across multiple distinct contexts, and the retention, use, or sharing of data derived from that activity outside the context in which it occurred.

Digital privacy is often used in contexts that promote advocacy on behalf of individual and consumer privacy rights in e-services and is typically used in opposition to the business practices of many e-marketers, businesses, and companies to collect and use such information and data. Digital privacy can be defined under three sub-related categories: information privacy, communication privacy, and individual privacy.

Do Not Track legislation protects Internet users' right to choose whether or not they want to be tracked by third-party websites. It has been called the online version of "Do Not Call". This type of legislation is supported by privacy advocates and opposed by advertisers and services that use tracking information to personalize web content. Do Not Track (DNT) is a formerly official HTTP header field, designed to allow internet users to opt-out of tracking by websites—which includes the collection of data regarding a user's activity across multiple distinct contexts, and the retention, use, or sharing of that data outside its context. Efforts to standardize Do Not Track by the World Wide Web Consortium did not reach their goal and ended in September 2018 due to insufficient deployment and support.

United States v. Google Inc., No. 3:12-cv-04177, is a case in which the United States District Court for the Northern District of California approved a stipulated order for a permanent injunction and a $22.5 million civil penalty judgment, the largest civil penalty the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has ever won in history. The FTC and Google Inc. consented to the entry of the stipulated order to resolve the dispute which arose from Google's violation of its privacy policy. In this case, the FTC found Google liable for misrepresenting "privacy assurances to users of Apple's Safari Internet browser". It was reached after the FTC considered that through the placement of advertising tracking cookies in the Safari web browser, and while serving targeted advertisements, Google violated the 2011 FTC's administrative order issued in FTC v. Google Inc.

Google's changes to its privacy policy on March 16, 2012 enabled the company to share data across a wide variety of services. These embedded services include millions of third-party websites that use AdSense and Analytics. The policy was widely criticized for creating an environment that discourages Internet-innovation by making Internet users more fearful and wary of what they do online.

Cross-device tracking refers to technology which enables the tracking of users across multiple devices such as smartphones, television sets, smart TVs, and personal computers.

Search engine privacy is a subset of internet privacy that deals with user data being collected by search engines. Both types of privacy fall under the umbrella of information privacy. Privacy concerns regarding search engines can take many forms, such as the ability for search engines to log individual search queries, browsing history, IP addresses, and cookies of users, and conducting user profiling in general. The collection of personally identifiable information (PII) of users by search engines is referred to as "tracking".