The geology of Great Britain is renowned for its diversity. As a result of its eventful geological history, Great Britain shows a rich variety of landscapes across the constituent countries of England, Wales and Scotland. Rocks of almost all geological ages are represented at outcrop, from the Archaean onwards.

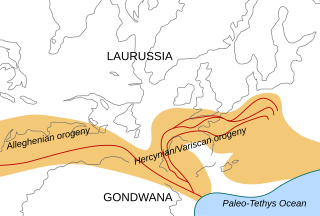

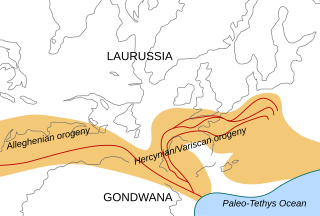

The Variscan or Hercynianorogeny was a geologic mountain-building event caused by Late Paleozoic continental collision between Euramerica (Laurussia) and Gondwana to form the supercontinent of Pangaea.

The London–Brabant Massif or London–Brabant Platform is, in the tectonic structure of Europe, a structural high or massif that stretches from the Rhineland in western Germany across northern Belgium and the North Sea to the sites of East Anglia and the middle Thames in southern England.

The geology of England is mainly sedimentary. The youngest rocks are in the south east around London, progressing in age in a north westerly direction. The Tees–Exe line marks the division between younger, softer and low-lying rocks in the south east and the generally older and harder rocks of the north and west which give rise to higher relief in those regions. The geology of England is recognisable in the landscape of its counties, the building materials of its towns and its regional extractive industries.

The Rhenohercynian Zone or Rheno-Hercynian zone in structural geology describes a fold belt of west and central Europe, formed during the Hercynian orogeny. The zone consists of folded and thrust Devonian and early Carboniferous sedimentary rocks that were deposited in a back-arc basin along the southern margin of the then existing paleocontinent Laurussia.

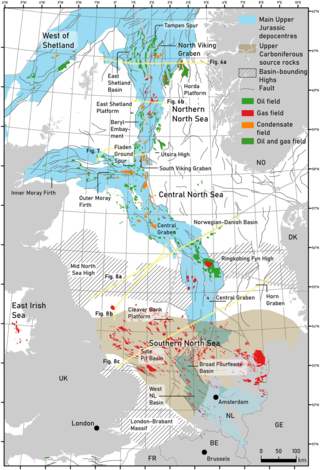

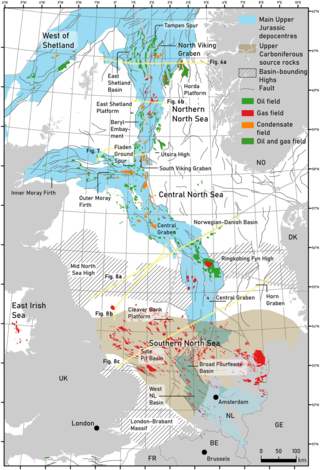

The geology of the North Sea describes the geological features such as channels, trenches, and ridges today and the geological history, plate tectonics, and geological events that created them.

The Saxothuringian Zone, Saxo-Thuringian zone or Saxothuringicum is in geology a structural or tectonic zone in the Hercynian or Variscan orogen of central and western Europe. Because rocks of Hercynian age are in most places covered by younger strata, the zone is not everywhere visible at the surface. Places where it crops out are the northern Bohemian Massif, the Spessart, the Odenwald, the northern parts of the Black Forest and Vosges and the southern part of the Taunus. West of the Vosges terranes on both sides of the English Channel are also seen as part of the zone, for example the Lizard complex in Cornwall or the Léon Zone of the Armorican Massif (Brittany).

The Aquitaine Basin is the second largest Mesozoic and Cenozoic sedimentary basin in France after the Paris Basin, occupying a large part of the country's southwestern quadrant. Its surface area covers 66,000 km2 onshore. It formed on Variscan basement which was peneplained during the Permian and then started subsiding in the early Triassic. The basement is covered in the Parentis Basin and in the Subpyrenean Basin—both sub-basins of the main Aquitaine Basin—by 11,000 m of sediment.

The South German Scarplands is a geological and geomorphological natural region or landscape in Switzerland and the south German states of Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg. The landscape is characterised by escarpments.

The Massif Central is one of the two large basement massifs in France, the other being the Armorican Massif. The Massif Central's geological evolution started in the late Neoproterozoic and continues to this day. It has been shaped mainly by the Caledonian orogeny and the Variscan orogeny. The Alpine orogeny has also left its imprints, probably causing the important Cenozoic volcanism. The Massif Central has a very long geological history, underlined by zircon ages dating back into the Archaean 3 billion years ago. Structurally it consists mainly of stacked metamorphic basement nappes.

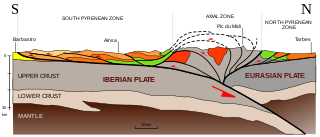

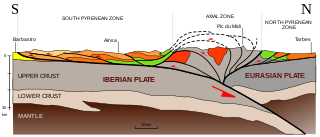

The Pyrenees are a 430-kilometre-long, roughly east–west striking, intracontinental mountain chain that divide France, Spain, and Andorra. The belt has an extended, polycyclic geological evolution dating back to the Precambrian. The chain's present configuration is due to the collision between the microcontinent Iberia and the southwestern promontory of the European Plate. The two continents were approaching each other since the onset of the Upper Cretaceous (Albian/Cenomanian) about 100 million years ago and were consequently colliding during the Paleogene (Eocene/Oligocene) 55 to 25 million years ago. After its uplift, the chain experienced intense erosion and isostatic readjustments. A cross-section through the chain shows an asymmetric flower-like structure with steeper dips on the French side. The Pyrenees are not solely the result of compressional forces, but also show an important sinistral shearing.

The Weald Basin is a major topographic feature of the area that is now southern England and northern France from the Triassic to the Late Cretaceous. Its uplift in the Late Cretaceous marked the formation of the Wealden Anticline. The rock strata contain hydrocarbon deposits which have yielded coal, oil and gas.

The North German Basin is a passive-active rift basin located in central and west Europe, lying within the southeasternmost portions of the North Sea and the southwestern Baltic Sea and across terrestrial portions of northern Germany, Netherlands, and Poland. The North German Basin is a sub-basin of the Southern Permian Basin, that accounts for a composite of intra-continental basins composed of Permian to Cenozoic sediments, which have accumulated to thicknesses around 10–12 kilometres (6–7.5 mi). The complex evolution of the basin takes place from the Permian to the Cenozoic, and is largely influenced by multiple stages of rifting, subsidence, and salt tectonic events. The North German Basin also accounts for a significant amount of Western Europe's natural gas resources, including one of the world's largest natural gas reservoir, the Groningen gas field.

The geology of Germany is heavily influenced by several phases of orogeny in the Paleozoic and the Cenozoic, by sedimentation in shelf seas and epicontinental seas and on plains in the Permian and Mesozoic as well as by the Quaternary glaciations.

The geology of Morocco formed beginning up to two billion years ago, in the Paleoproterozoic and potentially even earlier. It was affected by the Pan-African orogeny, although the later Hercynian orogeny produced fewer changes and left the Maseta Domain, a large area of remnant Paleozoic massifs. During the Paleozoic, extensive sedimentary deposits preserved marine fossils. Throughout the Mesozoic, the rifting apart of Pangaea to form the Atlantic Ocean created basins and fault blocks, which were blanketed in terrestrial and marine sediments—particularly as a major marine transgression flooded much of the region. In the Cenozoic, a microcontinent covered in sedimentary rocks from the Triassic and Cretaceous collided with northern Morocco, forming the Rif region. Morocco has extensive phosphate and salt reserves, as well as resources such as lead, zinc, copper and silver.

The geology of Luxembourg is divided into two geologic regions: Rheinisches Schiefergeblige in the north, extending into the Ardennes region in Belgium, and the Oesling Zone to the north of Ettelbruck. The country is underlain by the Hercynian orogeny related Givonne Anticlinorium, which mainly contains Early Devonian sandstone and shale. Rocks closer to the surface are primarily from the Cretaceous and are cut by the Sauer River and its tributaries.

The geology of Belgium encompasses rocks, minerals and tectonic events stretching back more than 500 million years. Belgium covers an area of about 30,507 square kilometers and was instrumental in the development of geology. The extensive outcrops in Belgium became the standard reference points in stratigraphy as early as the mid-19th century. Some of them are internationally recognized features related to the Carboniferous and the Devonian periods. These rocks were folded by two orogeny mountain building events --the Hercynian orogeny, and Caledonian Orogeny. Paleozoic basement rocks cover much of the country and are overlain by Mesozoic and Cenozoic sediments.

The geology of Laos includes poorly defined oldest rocks. Marine conditions persisted for much of the Paleozoic and parts of the Mesozoic, followed by periods of uplift and erosion. The country has extensive salt, gypsum and potash, but very little hydrocarbons and limited base metals.

The geology of the Czech Republic is very tectonically complex, split between the Western Carpathian Mountains and the Bohemian Massif.

The geology of national parks in Britain strongly influences the landscape character of each of the fifteen such areas which have been designated. There are ten national parks in England, three in Wales and two in Scotland. Ten of these were established in England and Wales in the 1950s under the provisions of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. With one exception, all of these first ten, together with the two Scottish parks were centred on upland or coastal areas formed from Palaeozoic rocks. The exception is the North York Moors National Park which is formed from sedimentary rocks of Jurassic age.